Lil business up top: Mac has an essay about the great Italian children’s writer Gianni Rodari in the New York Times Book Review.

As usual, Jon and Mac had this conversation over text.

MAC: Hi Jon.

JON: Hi Mac.

MAC: Today we are looking at... your new board books.

JON: Hooray!

MAC: So there are three, Your Forest, Your Island, and Your Farm. Do you want to set them up or should I?

JON: I feel like I probably should, but also I think I will ramble if I do, and I'm interested to hear how you would do it.

MAC: I was afraid you would say that.

OK! So each of these board books is about a specific place, and the action of the book is the creation of that space. They all begin the same way, "This is your sun. It is coming up for you." Each page introduces a new element — so in Your Farm, there is your barn, your horse, your truck, etc. After a new element is introduced, it joins the others.

MAC: I should probably mention that all the things have "the eyes," the "Jon Klassen eyes."

When the place is populated, night falls. The stuff goes to sleep. The eyes close. And the books all end the same way, too: "Now your farm is asleep. Now you can sleep too and think about what you will do there tomorrow."

(Except in Your Forest, it doesn't say farm, obviously.)

JON: (No, that would be incorrect.)

MAC: Done!

JON: Well, that was way better than I would've done. I would have wandered off right away.

MAC: Before we get deeper into how these specific books work, I have a question that might not be interesting.

JON: Oooh.

MAC: Do you think a board book is a type of picture book, or something else entirely?

JON: I think it's a type of picture book! It has some different rules, technically, and maybe different assumptions of what the reading of it will be like, but I think conceptually this didn't feel too unfamiliar. The main difference was that it can, and maybe was expected to be, a lot shorter. That changes everything right away.

MAC: OK. I also think it's a type of picture book.

JON: Phew.

MAC: Yeah.

JON: Would've been pretty weird in here after if we didn't agree on that.

MAC: Plus we'd have to start a new Substack just for this post, probably.

OK, do you want to go into some of those different rules you mentioned above? You don't have to make edicts. I know you don't like edicts.

JON: I like SAYING them.

MAC: And then caveating them into oblivion.

JON: It is my way.

MAC: How did you feel liberated or obligated to make these books work differently?

JON: I thought about you a lot when I was making these, actually! I think about you anyway, but, in making these, I was very glad to have watched you work all these years, because I was finally in the zone that you seem to come so naturally to, which is the assumption, or anyway the starting point, that these will be read aloud.

I don't usually do that. For my other books, I always started with the idea of a reader by themselves, reading in their heads. And then I try to make sure I take care of the read-aloud scenario later.

MAC: That makes sense — something that's very powerful about these books is the second person. It is an adult bestowing all this stuff on a kid.

JON: They got interesting, or viable, creatively, when that came in.

Like, I like the basic setup, where we are constructing places over a series of pages, and the gutter of the book acts like it's establishing these two trays, moving pieces from one tray to the other. All that stuff was in there, but I don't think I knew we had books, specifically, until I got brave enough to try the second-person thing.

MAC: They feel very generous and intimate. The adult reading this book aloud to a kid — probably a very young kid — is making a world and giving it to them.

When you first showed them to me, I was surprised by how emotionally charged they were.

Because of the relationship they set up between grown-up and kid.

JON: THAT was new too, and it got really fun then. To acknowledge that we WANT to give stuff to the person we're reading these to, and that it feels good, even just physically, to say: "Here is this. This is yours." Even though you can't actually give them what it says you are giving them. It just feels good to say it out loud to them, and none of that had ever been a reason for me to write anything before.

MAC: How much of this is rooted in your own experience as a father and/or reading to your own kids?

JON: It's the first time that was directly related, for sure. I have a clear memory of trying to engage our second son, Auggie, when he was really small, in an alphabet book. And one of the things I'd try for some reason was to point to the apple or the truck or whatever and say: "Look, that's like your truck," or "You had an apple today, that's like yours." I don't remember how effective it actually was in getting him more involved, but it was an impulse I had. But some of this is also rooted in the idea of the copy of the book itself, that we go on tour and see other kids with their books, their copies, and they know there are a lot of other copies, but they are still holding theirs, and me kind of saying this time: "THIS one is yours," right in the book, page after page. I liked saying it. It got to that idea of the book as an object, in the end.

MAC: Right, there's a way in which these feel like they’re documenting the process of a book being made. Or even the stuff that happens before a book gets made. Like, if you, Jon, were setting a book in a forest, you would draw the trees, and then the rock, and then the cabin, and then you’d arrange them. And that would be your setting. And then you would start telling the story.

But what you've done here is say, "What if I didn't tell a story?"

JON: Yeah, it was a fun challenge to be like, "What if nobody has a problem?"

How else do you make something feel like it starts and ends?

MAC: This is something we talked about with each other when our kids were really young — the way that something can have the rhythm of narrative, but no plot.

I think you really nail that here!

JON: It gets to what we also talk about a lot, that we feel like very young readers are up for things that don't rigidly work like traditional stories. If it feels like something ends, that's valid.

MAC: Your Farm is the most straightforward. We move from visual emptiness to abundance, and then everything goes to sleep.

JON: Yeah, it was kind of intentionally the most straightforward. Like, it looks the most like a traditional toy set, it has brighter colors. But also part of the fun here is that you're giving them little places that ideally sustain themselves, right? And farms are great symbols of that. Plus, there's a truck. The publisher was very happy about the truck. There will probably be more trucks, later.

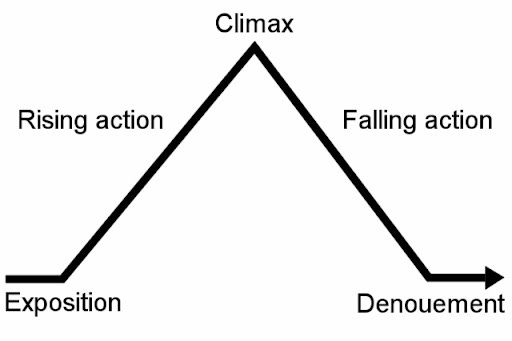

MAC: The book follows Freytag's Pyramid, although technically nothing happens.

Can you Photoshop a truck onto that pyramid?

JON: Sure, I'm putting him all over the place these days.

MAC: The other two books start to play with structure a little bit.

And this may seem silly to get into for books that are, what, 22 pages?

But when you introduce eccentricities in a book that short, even for a page or two, it really affects the reading experience!

So in the middle of Your Forest, you introduce a ghost.

But instead of following the pattern of moving the ghost into an arrangement with the other objects, you say, "He only comes out at night."

And then on the next page he is gone.

(You also say, "He is nice." Smart move.)

JON: (Not gonna pretend "he is nice" was in there before the publisher saw the ghost.)

MAC: ("He is not vengeful.")

JON: ("His business is not unfinished.")

MAC: But this move — introducing the ghost and taking him away, saying he only comes out at night — sets up suspense. We're now waiting for the ghost to come back. And if the kid has read the other books, they know that the last page is going to be night. And if the kid hasn't read the other books, they may know night is coming from, well, experiencing time.

JON: Yeah, and in the pages after that, I tried to change the subject as much as possible, introducing the only sequential pair of things in any of the books. There's a stream and then on the next page a bridge to go over the stream, to really try to make you forget about the ghost a little bit.

MAC: And then, sure enough, on the last spread, boom.

JON: There he is. For sure being nice.

MAC: It's Chekhov's Ghost.

(Not, like, the vengeful ghost of Anton Chekhov.)

JON: I actually debated putting it in a lot. I was proud of the other two, that they didn't have, or maybe (hopefully) didn’t require that complication. It felt like I had pulled something off with those, not needing that last beat, and we could've just done the same with the forest one. I don't think it would've been bad. I still like the ghost a lot, but he felt like a small concession to…something, on my end, to think it needed that extra thing. I don't regret where it ended up, but I remember wondering about it a lot.

MAC: I feel like Your Island has two little complications.

One is the fire.

"This is your fire. It is a magic fire. It will never go out."

You introduce magic here. It changes the rules of the island.

This is another page that feels emotionally charged for me.

Very The Road.

JON: Yeah, or that speech at the end of No Country for Old Men about his dad carrying fire in a horn.

MAC: And then the bird. "This is your bird. He flies away sometimes but he always comes back."

Again, this is a little different. Although the bird hangs out for the rest of the book, there's a tension knowing that he could fly away, and a comfort to knowing he will always come back.

The fire that never goes out and the bird that always comes back are both explicitly reassuring us about potentially inconstant things.

JON: I think, maybe, that's why these books generally felt emotional to make. They are, when you see them, pretty straightforward, just making places and naming the parts and everyone goes to sleep, but the reasons I wanted to make them were very personal. They're about making something solid and calm and even predictable, even if everyone understands they’re not real. The books all end with nothing but a place, a very stable place, being established. But the book choosing to end with that, and only that, seemed to be saying “Yeah, that’s a statement of its own. Making this exist somewhere, anywhere, is enough reason to do it." It says something about what we might feel about the world now. And also probably how it’s always felt to have a child who will go forward into the unknown, where eventually you will not be.

MAC: Yeah, as an adult, it doesn't always feel that we are able to hand a good world over to our children. And that's painful.

And kids don't really get to own stuff, which is frustrating. So there's a lot of pathos here!

JON: Yeah, here the kids get to own stuff, both in a real and fake-way. They get a book, but also all this stuff we're saying is theirs even though it's intangible, but also the reader gets to say out loud: "here you go." So, everyone kind of gets an itch scratched even though the kids don't actually own a forest, and the adult actually doesn't have one to give them, really.

MAC: The book is also cheaper than an actual forest, which is nice.

JON: We won't get into what its production probably DID to forests, though.

... Anyway, I hope people like these books.

"What if nobody has a problem?" feels almost radical when it comes to the idea of story structure. But it's kind of welcome these days, and also a satisfying entry to the rhythms of story for the youngest "readers" who will encounter these books.

"Reassuring about potentially inconstant things" feels like the most important gift we could give our children right now. Thank you, Jon. I love these conversations so much... and I'm grateful for the dive into board books which are so seldom explored from a craft perspective. Curious to know if the 22 pages was a limit you were working with while writing, or whether the story dictated the page count? I know board books can be shorter, but maybe not longer...