Millions of Cats

Jon and Mac consider: a breakthrough in book design, rivers of cat blood, children's stories about old people who love each other, and whether Wanda Gág invented the picture book.

Jon and Mac had the following conversation about Millions of Cats over text.

JON: HI MAC!

WHOA

caps lock

MAC: I was wondering why you were so enthusiastic. Out of character.

JON: Yeah it is not representative of my mood for sure.

Not that I’m not excited. I am excited for our book choice today. Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág!

MAC: First off, a bit of reader service.

Her last name is pronounced “Gog.”

JON: Kind of neat too cause “Wanda” is pronounced “Wonda.”

Thought that was worth noting.

MAC: That’s a great point, Jon.

JON: This book is such a good book.

MAC: Millions of Cats was published in 1928, which will be relevant for a few points in our discussion, but most immediately it means that you can read the whole thing right now for free, because it is in the public domain.

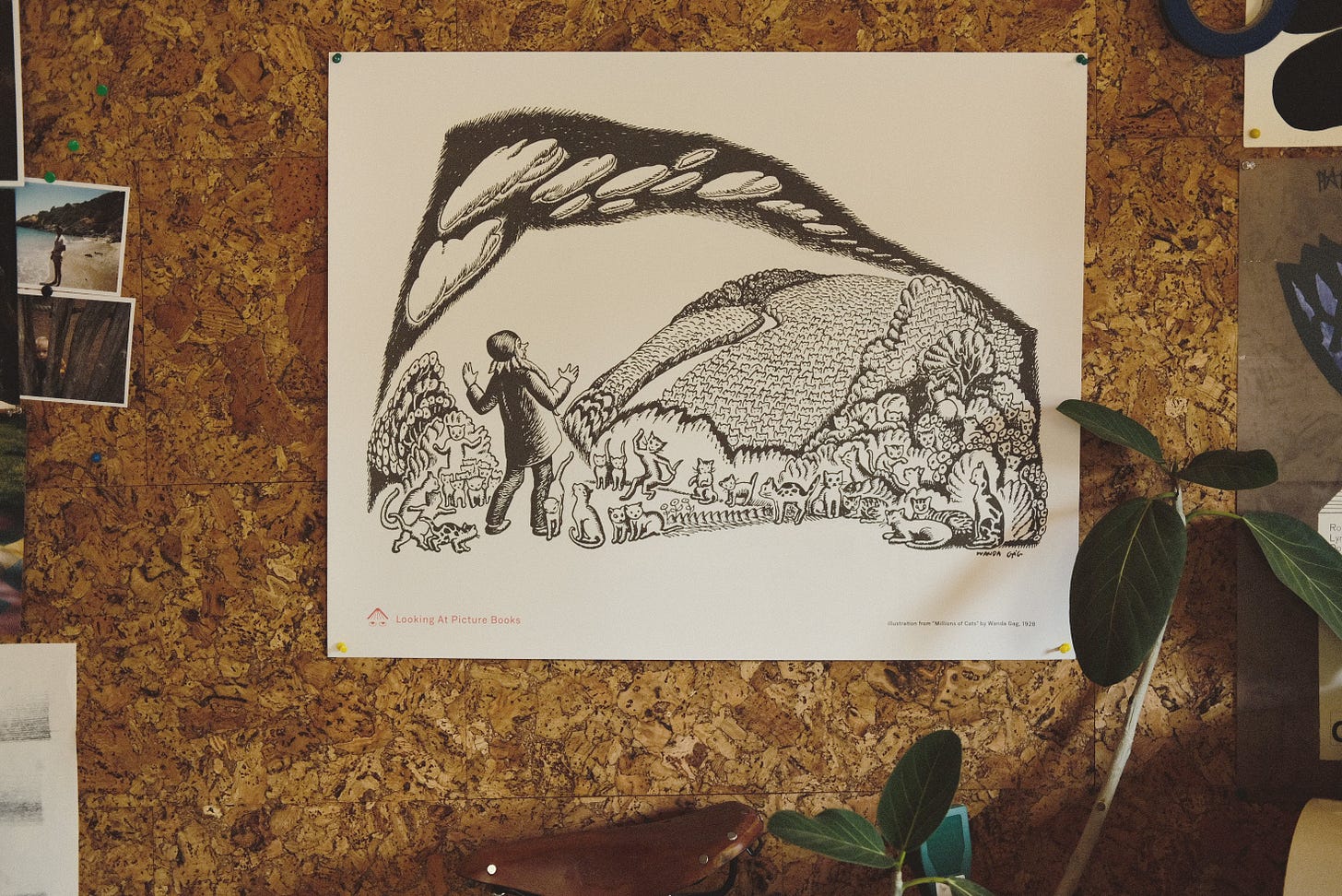

JON: It also means that we can sell high-quality posters with an image from Millions of Cats.

These posters are not only well-made and very nice to look at, but they are also, conveniently, very appropriate to the spirit of this Substack, given what this book means to the history of the picture book.

MAC: Because Millions of Cats is the First Picture Book.

At least, that’s what I think.

There were illustrated books for children before Millions of Cats that feel picture book-ish. You see flickers of the techniques that define picture book storytelling. Randolph Caldecott’s illustrated editions of nursery rhymes, for example, in which the illustrations expand and sometimes even change the story set out in the text.

And there are plenty of books that come after Millions of Cats that get called “picture books” but feel leaden and old-fashioned because they don’t take full advantage of the picture book’s formal possibilities.

I don’t want to name names.

(Make Way for Ducklings.)

JON: (OH NOOOOO)

MAC: When Wanda Gág wrote Millions of Cats (which was her first book), most illustrated children’s books were not original stories. They were inherited texts: nursery rhymes, fairy tales, folk tales, Bible stories.

JON: Right, and a lot of those books, the way they were laid out was very austere. The illustrations were often full pages, separate from the text, which was often long-winded and not referring to the drawings directly at all. The drawings were maybe tipped in on different paper because of printing methods, so everything just felt very stiff and formal.

MAC: Sometimes illustrations would appear alongside the text, but their function was more ornamental than narrative—like in an illuminated manuscript.

JON: And then this book comes in, and everything is fluid and moving and working together.

MAC: Yeah, this is a story intended to be told in words and pictures, intermingled on the page, and sharing the storytelling duties. Gág designs this story to be a picture book, both in the way she constructs the text to interact with her pictures, but also literally: it’s a breakthrough in book design. She establishes a lot of the grammar for a new literary form.

JON: Let us look...at this picture book.

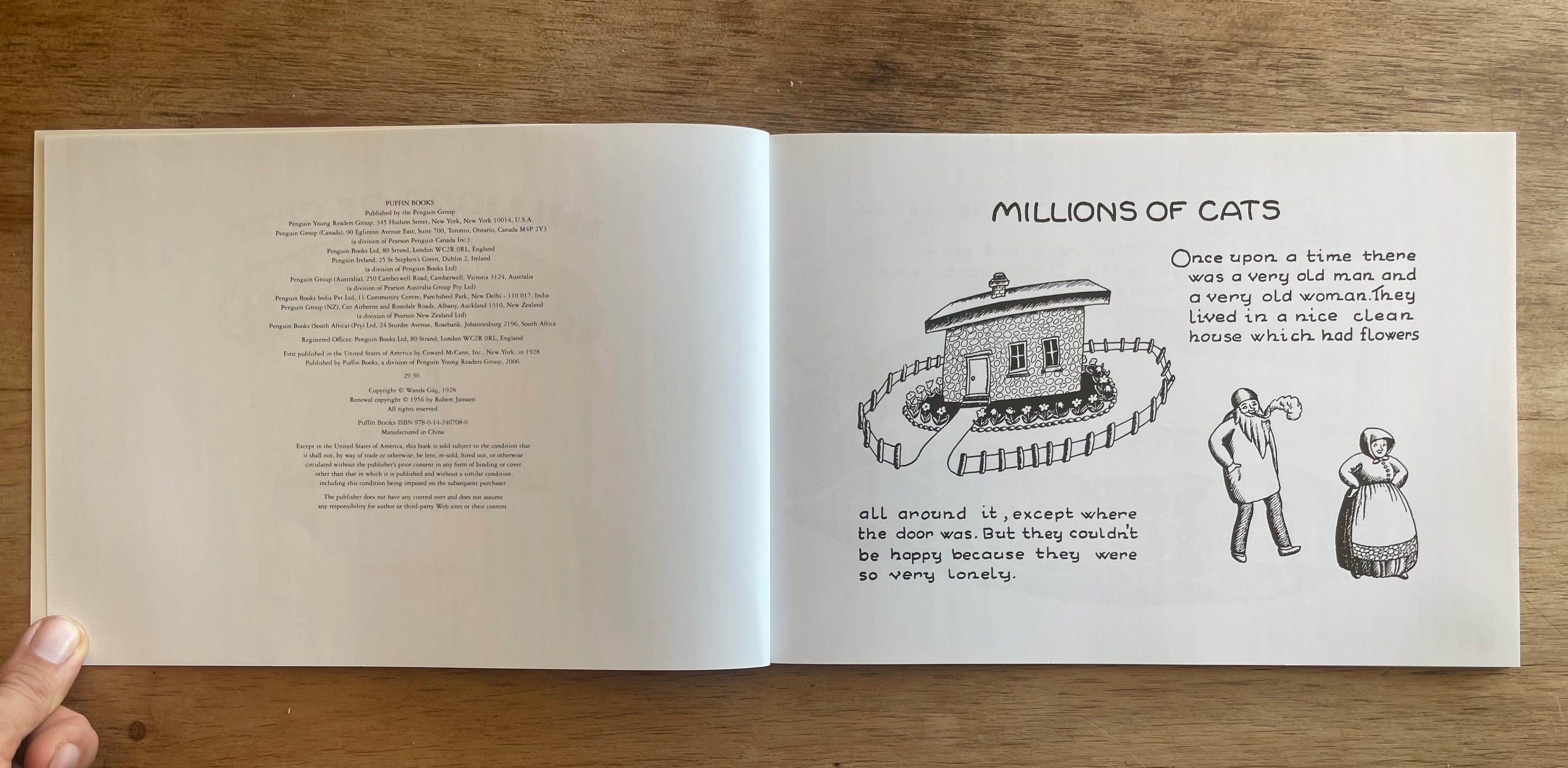

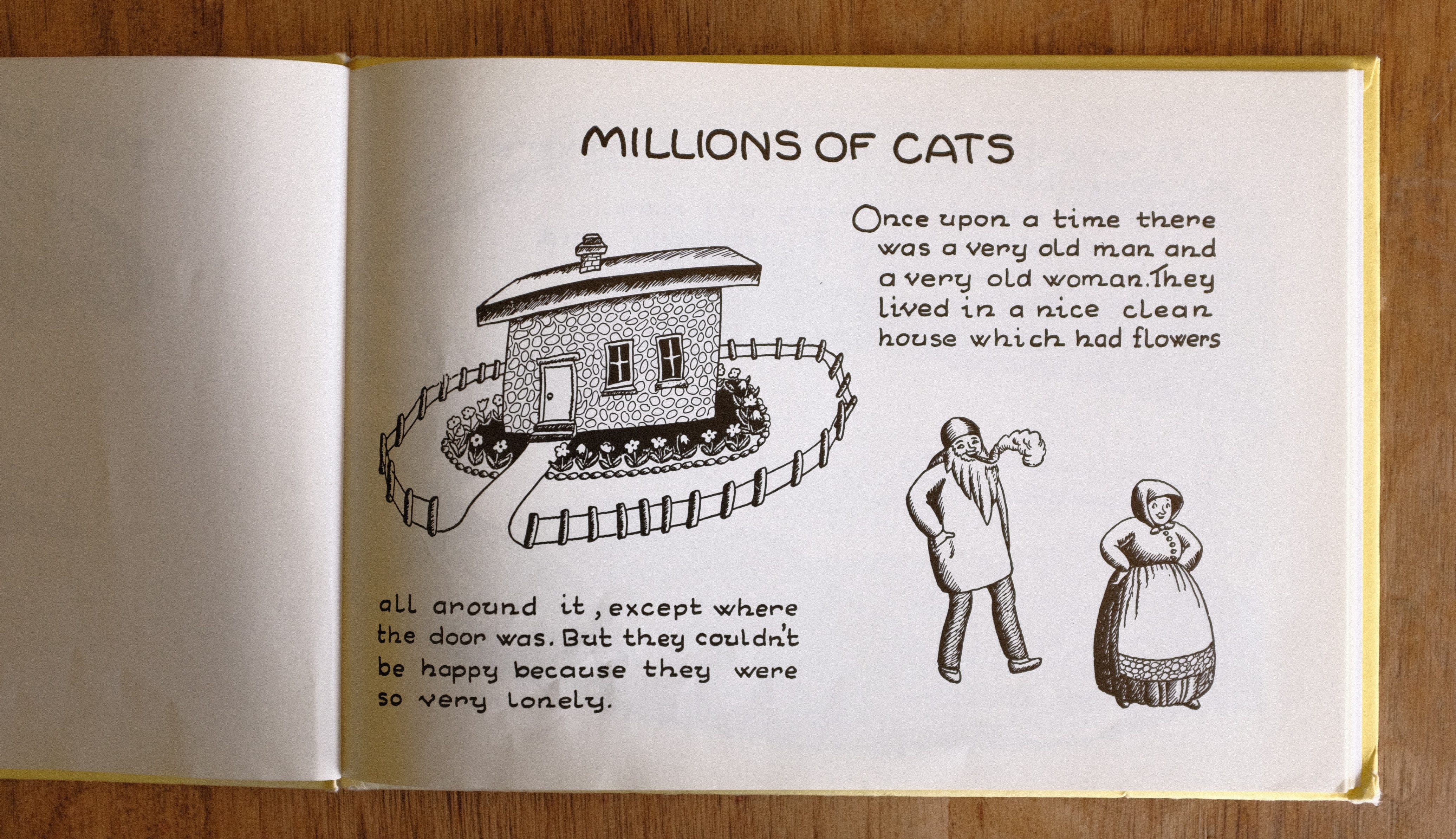

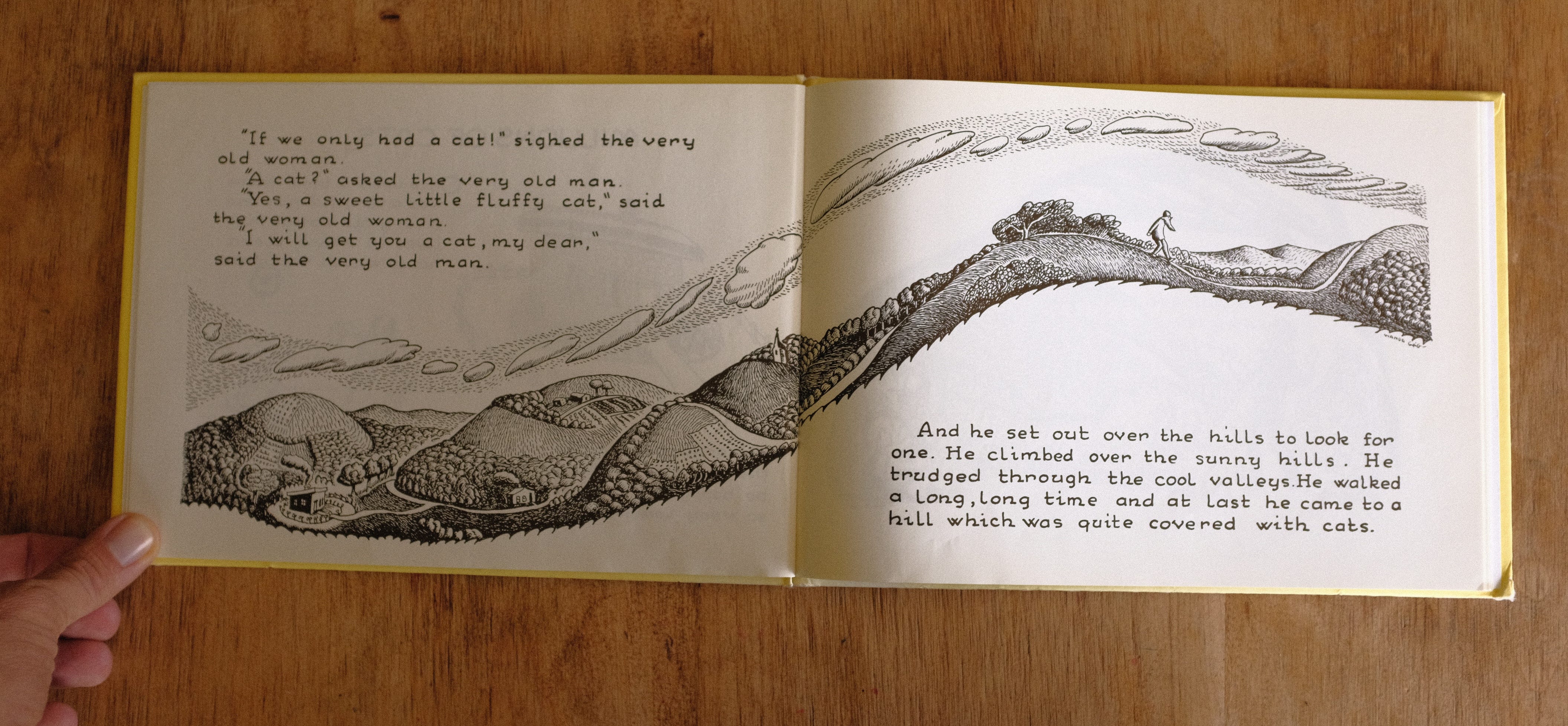

MAC: A picture book unfolds as series of spreads, two pages separated by a gutter. How those spreads are laid out affects the reader’s experience.

Here is the first spread, which, technically, is actually not a spread, because the left hand side has the copyright information, which is no longer relevant, because the book is in the public domain, please buy our posters.

MAC: There are two small illustrations and text that refers to them. This is a very utilitarian layout, good for exposition: here are your characters, here is their house, etc.

JON: We talk a lot about using the pictures and the words to tell different aspects of a story, and Gág does that in Millions of Cats, but it’s also fun to see when she kind of rides the line. Even on the first page, she describes the very old man and the very old woman and their house, and she says that it “had flowers all around it, except where the door was,” and even though that is redundant to the drawing of the same thing, there’s something so satisfying about checking on the drawing once you've heard that and going, “Oh yeah, lookit!”

MAC: I take your point, but: “flowers all around it, except where the door was” is also a surprising—and kind of confusing—way to describe something we’ve all seen a million times before. She’s talking about a… path. The image of the house resolves an ambiguity created by the imprecise and playful language. Because there is a picture there, Gág can use a novel term for a familiar thing. And isn’t that what it is like to be a child—to see afresh a world other people have built?

JON: There’s also a disconnect here between how she has drawn the couple and how she has written about them. The text says they can never be happy because they were lonely, but when we check on the drawing, they seem okay! They’re smiling! And this tells us something about their characters. Yes, they’re sad, but not like, all the time sad. Their problem is sad, but they are generally happy people.

MAC: But all in all, this first page is a traditional way to lay out an illustrated story for children, and would have felt familiar to readers in 1928.

JON: And then we turn the page.

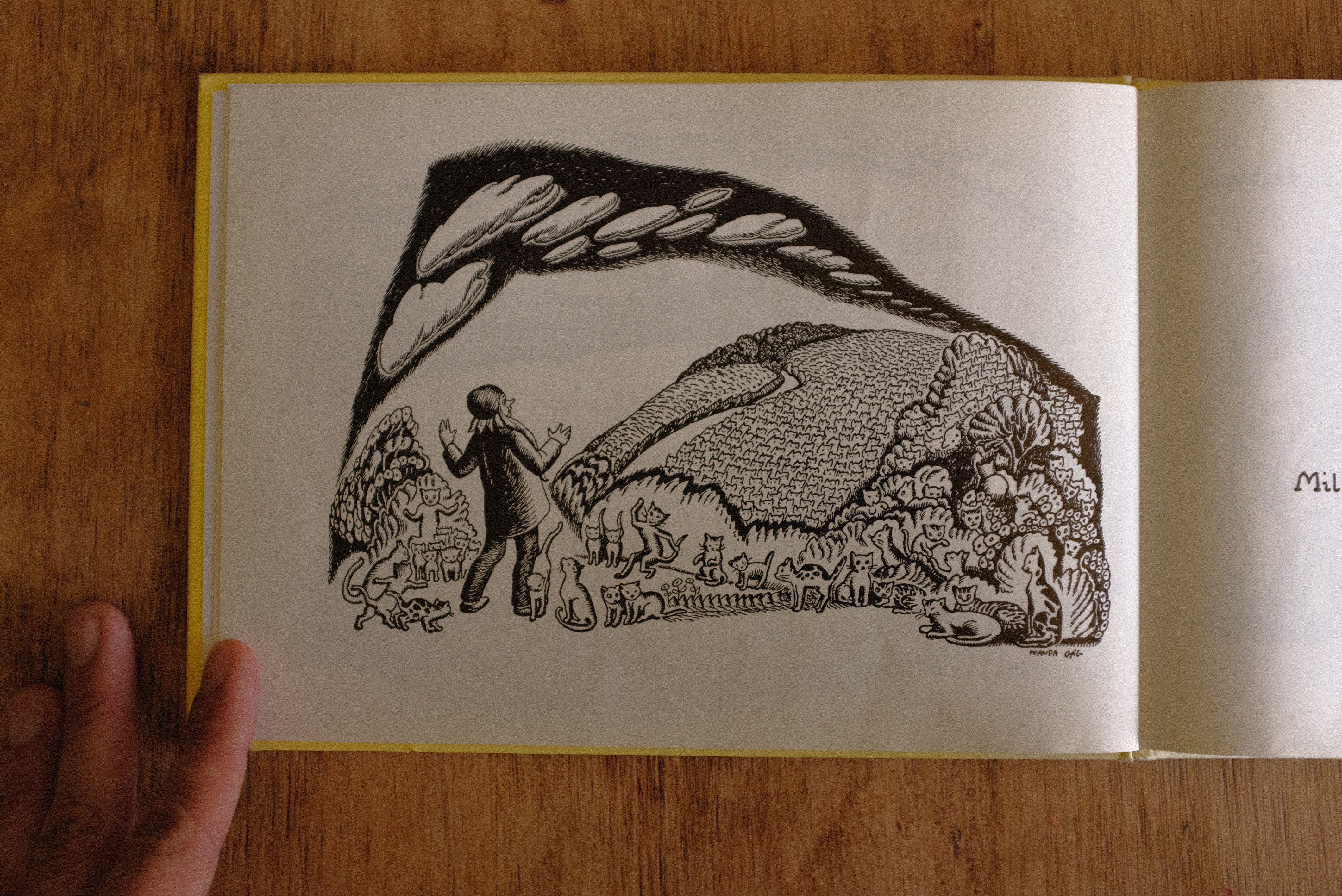

MAC: We open up on an illustration that crosses the gutter and fills the entirety of our two pages. This is called a two-page spread. And, in fact, this is the first two-page spread in the history of picture books. Wanda Gág just invented it. That’s literary history right there!

This spread must have felt fresh to readers. A surprise. But almost 100 years later, a two-page spread can still surprise in picture books, when it’s used right. Alternating single-page layouts with two-page spread alters our experience of the story—it’s a way of playing with the reader’s sense of space and time.

It's very dramatic, to move from the cramped composition on the preceding page to this vista, and it supports the storytelling, because the man is going on a long journey, and we now learn that the world of this book is much bigger than the first page indicated.

JON: Another thing here is that she is designing the illustration to fit the blocks of text. She’s bending it around where the text will go. It’s all very conscious of the pieces, literally flowing together.

MAC: Did you know her brother hand-lettered this book?

JON: I did NOT.

That rules.

Did he do the cover type too?

MAC: Yes.

JON: How much do you know?

MAC: Try me.

JON: Those are all my questions.

MAC: Phew.

MAC: The way the text is placed next to the illustration warps time. The first bit of text describes a conversation between the man and the woman that has happened before this scene, and which we will never see illustrated—the pictures have gotten ahead of the story.

JON: Then her paragraph about him setting off over the hills is set directly below him walking over the hills. It’s so clear and fun.

But soon it falls behind the story! In the second paragraph he walks and walks and finds a hillside filled with cats! We don’t see that yet!

MAC: It makes us want to turn the page.

We wanna see those cats.

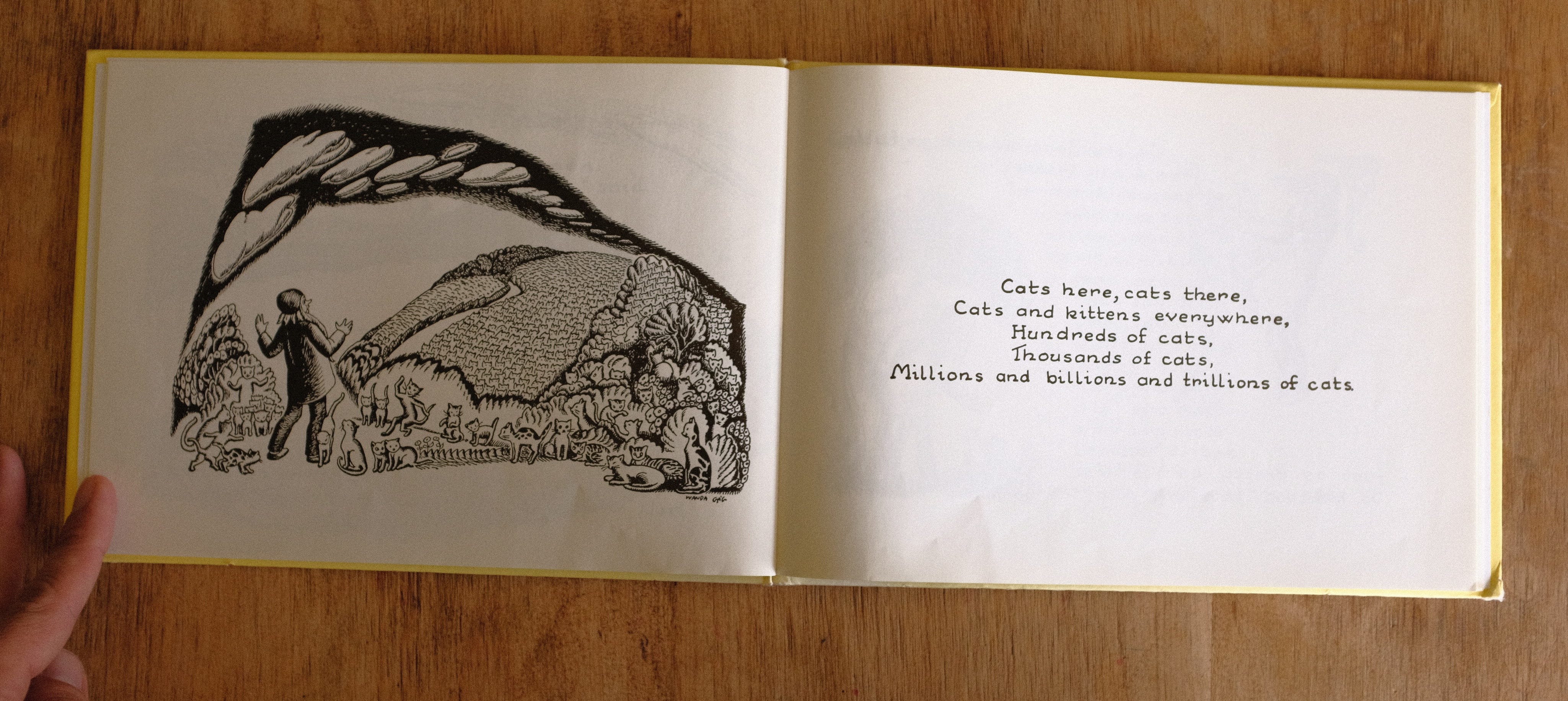

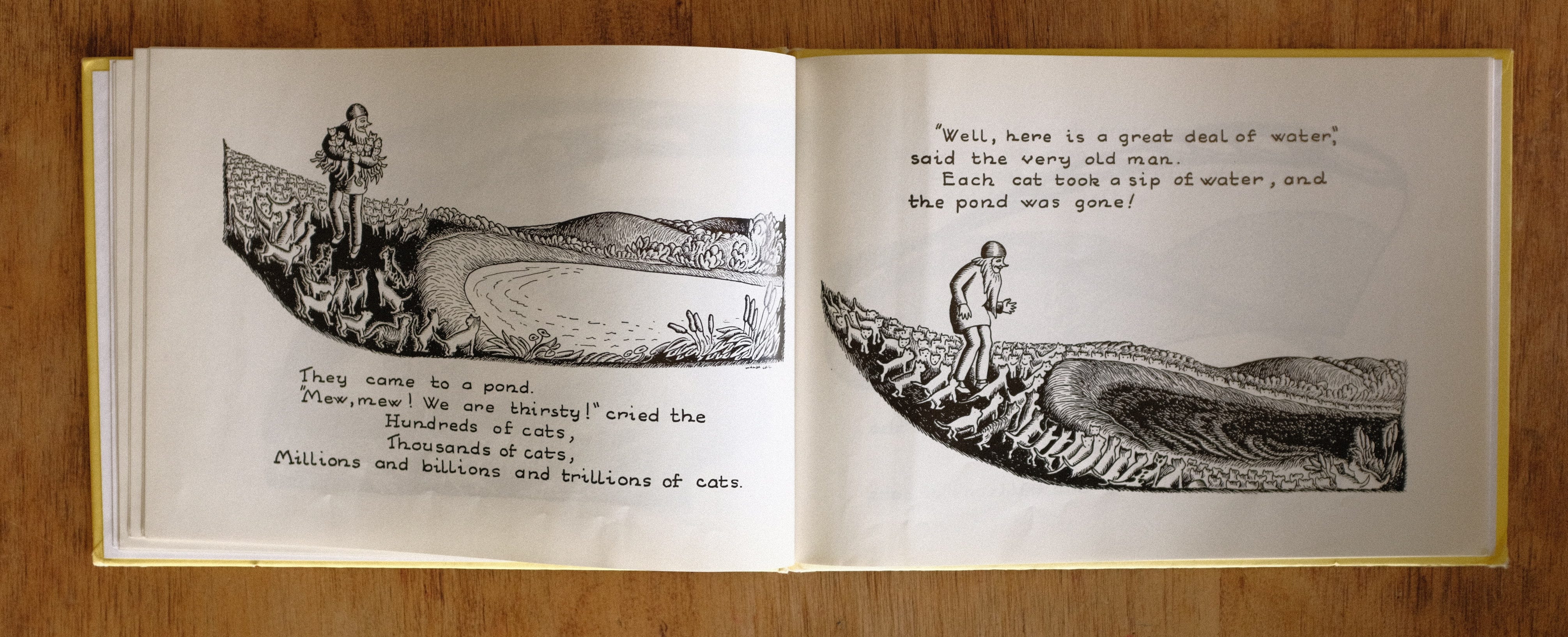

JON: This is another reason this story is especially a picture book story. If you read a short prose story called “Millions of Cats” and it talked, in words only, about tons and tons of cats, you'd be like “okay” but for this book she’s like “you guys wanna see me draw a LOT of cats?”

AND she delivers. I remember as a kid, being super skeptical. “Let’s see these MILLIONS of cats."

And every time this page comes up you’re like “Oh that really is millions of cats.”

MAC: Billions

JON: And trillions of cats.

MAC: She really does draw a lot of cats.

JON: And this is where Gág’s way of drawing pays off too. Not only is “millions of cats” a great idea for a picture book generally, it's a great idea for a picture book by HER. Because her way of rendering makes it possible for you to feel like you are looking at endless cats.

This is, as an aside for the illustrators, a great habit to get into: playing to what you know you in particular can draw especially well. She wrote this story for herself because she was like “I can do that.” It seems simple, but how often have you gotten half way through a job and been like, “I can’t draw this why did I say I would draw this.”

I mean, I never have.

But I assume some people do.

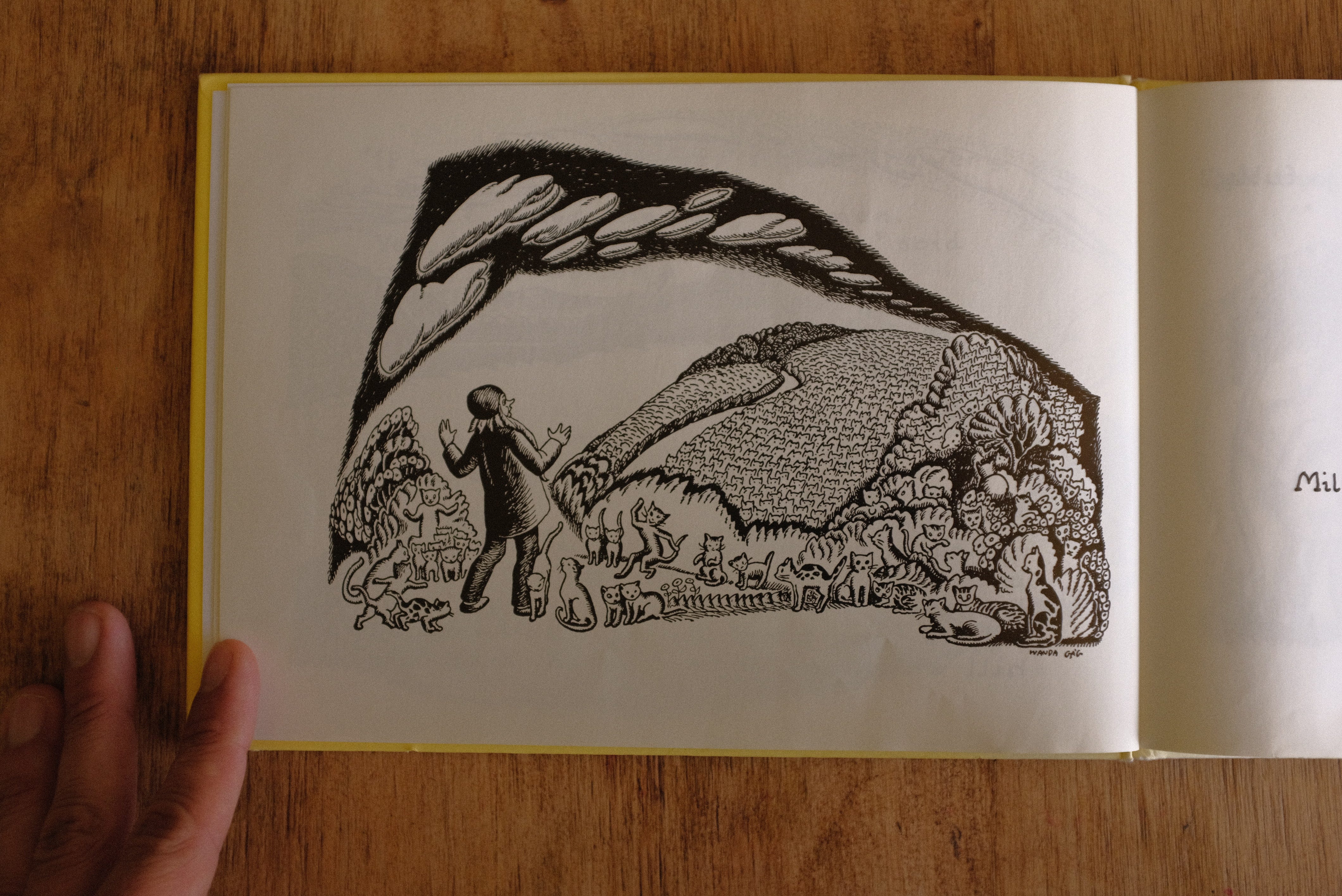

MAC: It’s an incredible opening—so much has happened in these first three spreads, and the narrative is supported by these three different layouts.

First: Cramped, intimate, domestic.

Second: Two-page spread with a huge vista making us feel like we’re on a big journey.

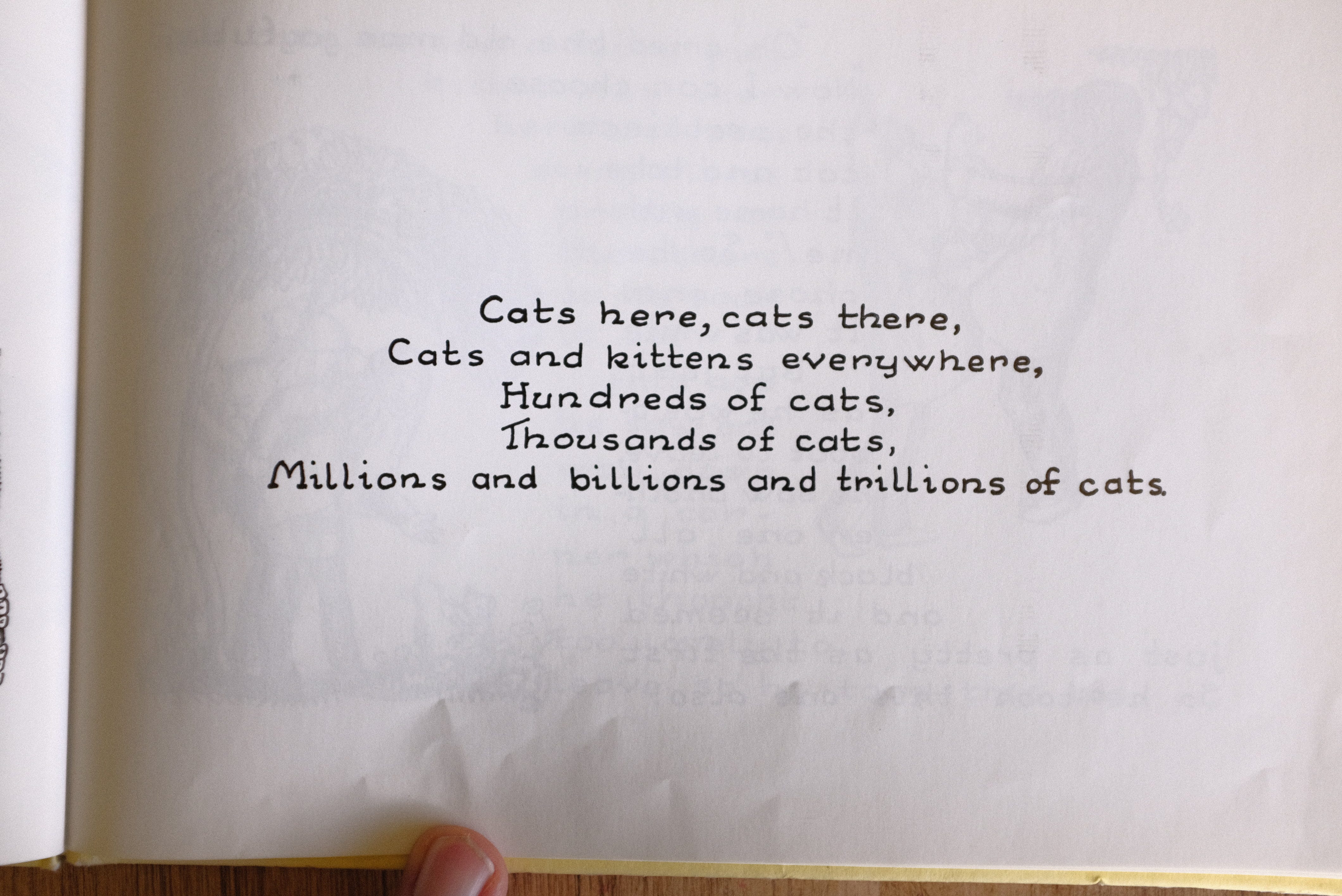

And third: This astonishing moment where our hero sees something miraculous. And the layout here does that too. It’s a big picture on the left, with no words on the page, and the text over on the right is like, hey, look at that.

Just like the man, the text has been stopped short by the sight and is pausing to take everything in.

JON: And you could argue that this is a less exciting layout, more like the traditional text-on-one-side-picture-on-the-other that we were talking about earlier, but I think what makes it exciting is the writing. The writing is not a paragraph that could live on its own. You wouldn’t write it that way if you were just writing a story. She is designing a paragraph to accompany the picture that will pay off what she’s saying. You’re bouncing back and forth between the two sides. You see the picture and you’re like “that’s a lot of cats!” and then the text is upping that, saying “it’s hundreds of cats” and you look back and you’re like “yeah seems right” and then text says “Thousands,” “Millions,” “billions and trillions” and you just keep looking back at the picture and it keeps sounding right!

MAC: Yeah, the language here feels ecstatic. In the words, she has abandoned the storytelling and launched into song. The narrative—what this means to the man emotionally, where he is standing, what it even means for there to be cats everywhere—is handled by the illustration. The text is working here just to establish exuberance, to amplify the abundance in that picture.

JON: I think that gets into what this book discovers, is that picture books move like songs.

Or they can, anyway.

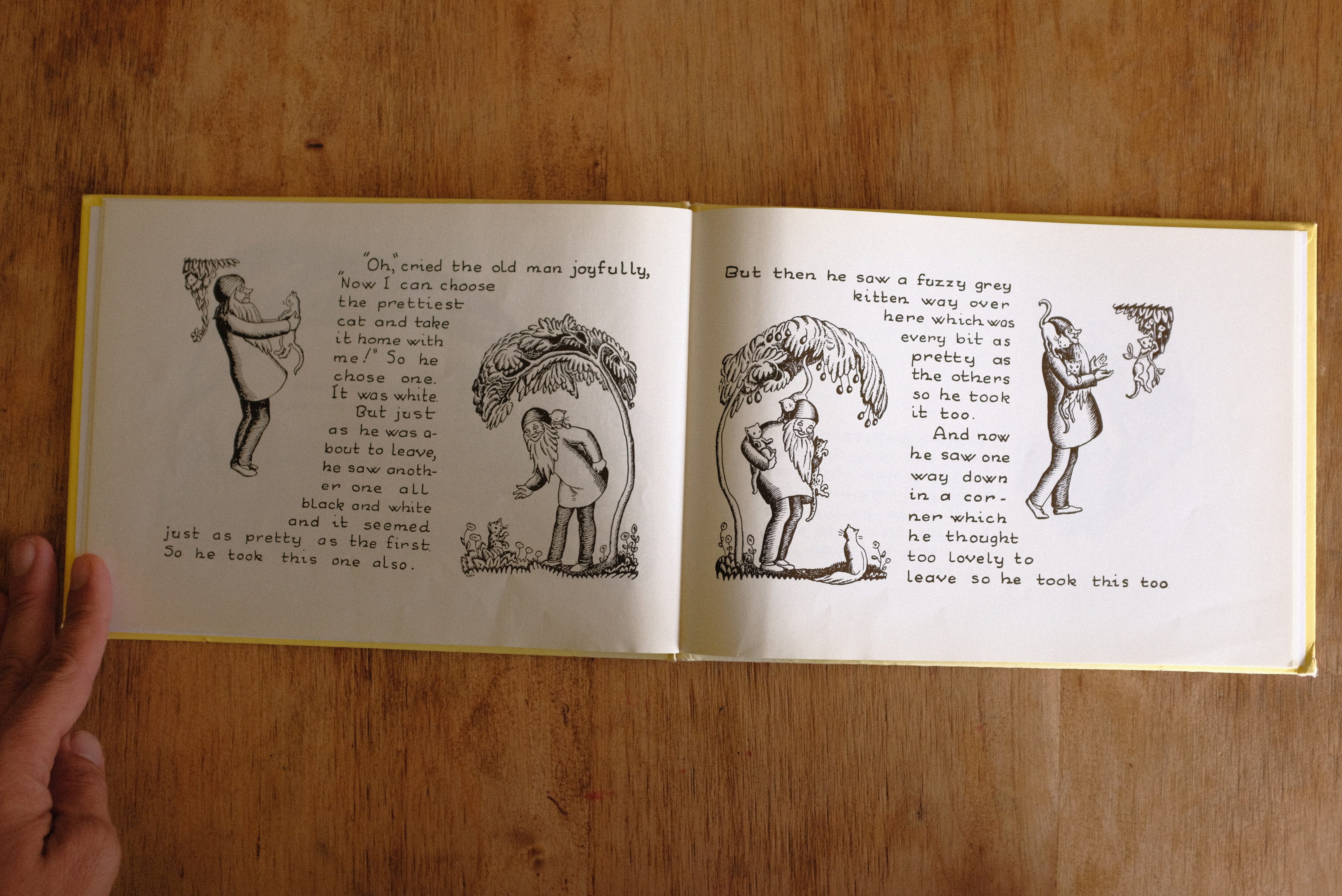

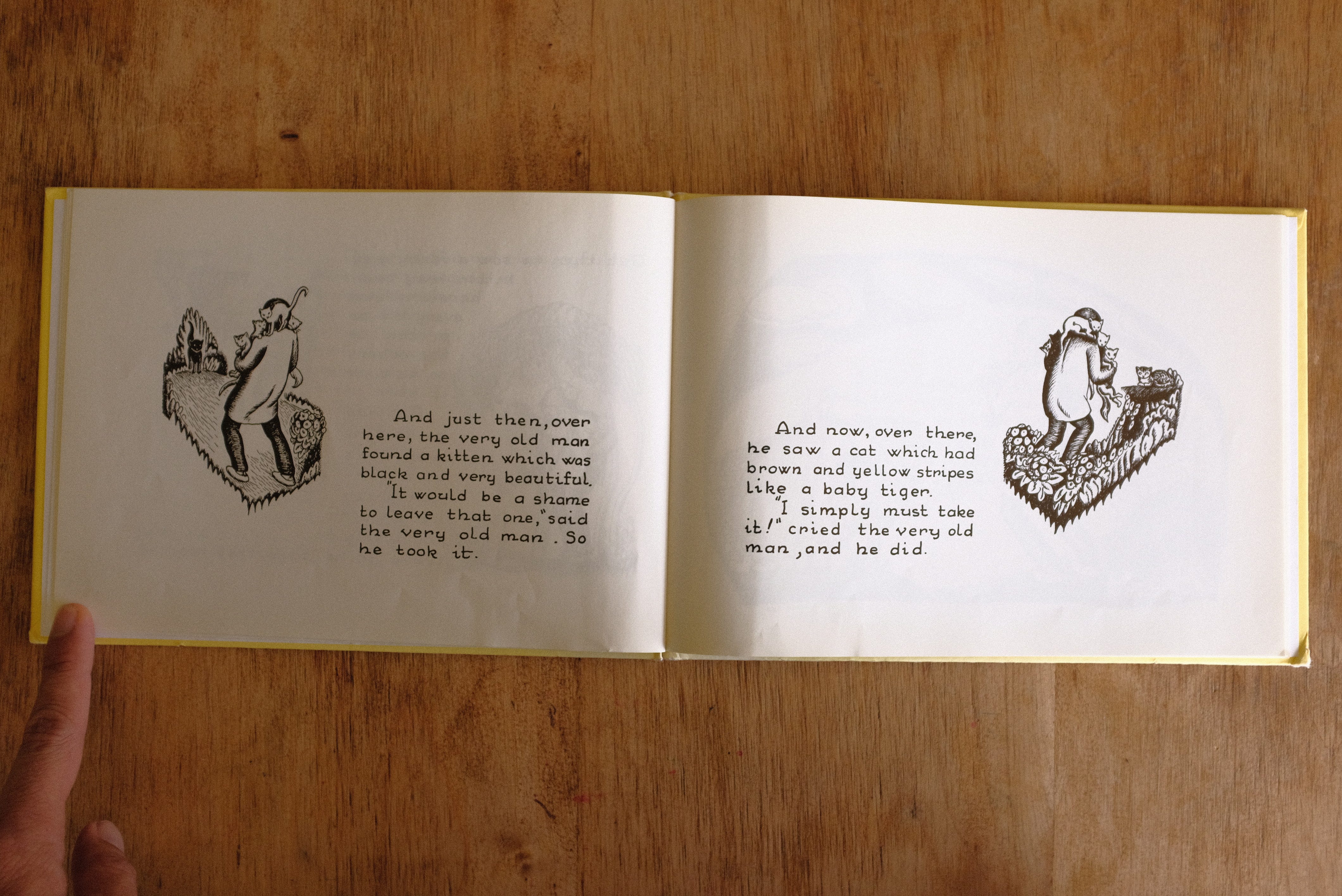

The next two spreads are, again, a new layout idea, and used so effectively.

MAC: Yeah, in these spreads, the man is just reveling in how many cats there are.

JON: Both of them are symmetrical layouts, each side of the gutter the characters and action facing opposite ways.

JON: This layout consciously addresses the fact that we have an open book with a gutter down the middle, but what she's doing by having the man face this way and that is the audience begins to feel directionless, or lost. You can do this to disorient your readers, if that's your goal, but here the effect is more gentle. He’s overwhelmed by choice.

MAC: It reminds me of the “Pure Imagination” scene in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, where it’s just cutting around to the kids finding new kinds of amazing candy. Except with cats.

JON: The other benefit to this layout is that she isn’t drawing all those cats over and over. You’re getting the impression of a lot of cats, but we’re really only seeing like, eight cats.

MAC: You get the feeling that the man is “exploring the space”—both of the hill and the physical space of the book—and that everywhere he turns there are cats.

“How do you draw a trillion cats but only draw eight cats?”

A real Jon Klassen-type question.

JON: Indeed.

Though I would say too that she’s being mindful of her audience there. It’s faster to draw, sure, but we’ve seen and will see again she’s not shy about drawing hillsides of cats when it counts. It’s just that the viewer might get a little tired of it if she draws all those cats every time.

MAC: No for sure.

You would get excited about wriggling out of drawing all these cats.

But not Wanda Gág.

She’ll draw the cats.

JON: Yeah you would get to the end of my book called “Millions of Cats” and say “you only drew 8 cats, like, total” and I would be like “pretty clever of me right? I made you IMAGINE the rest” and you would say “Iiiiii wanted to see more cats.”

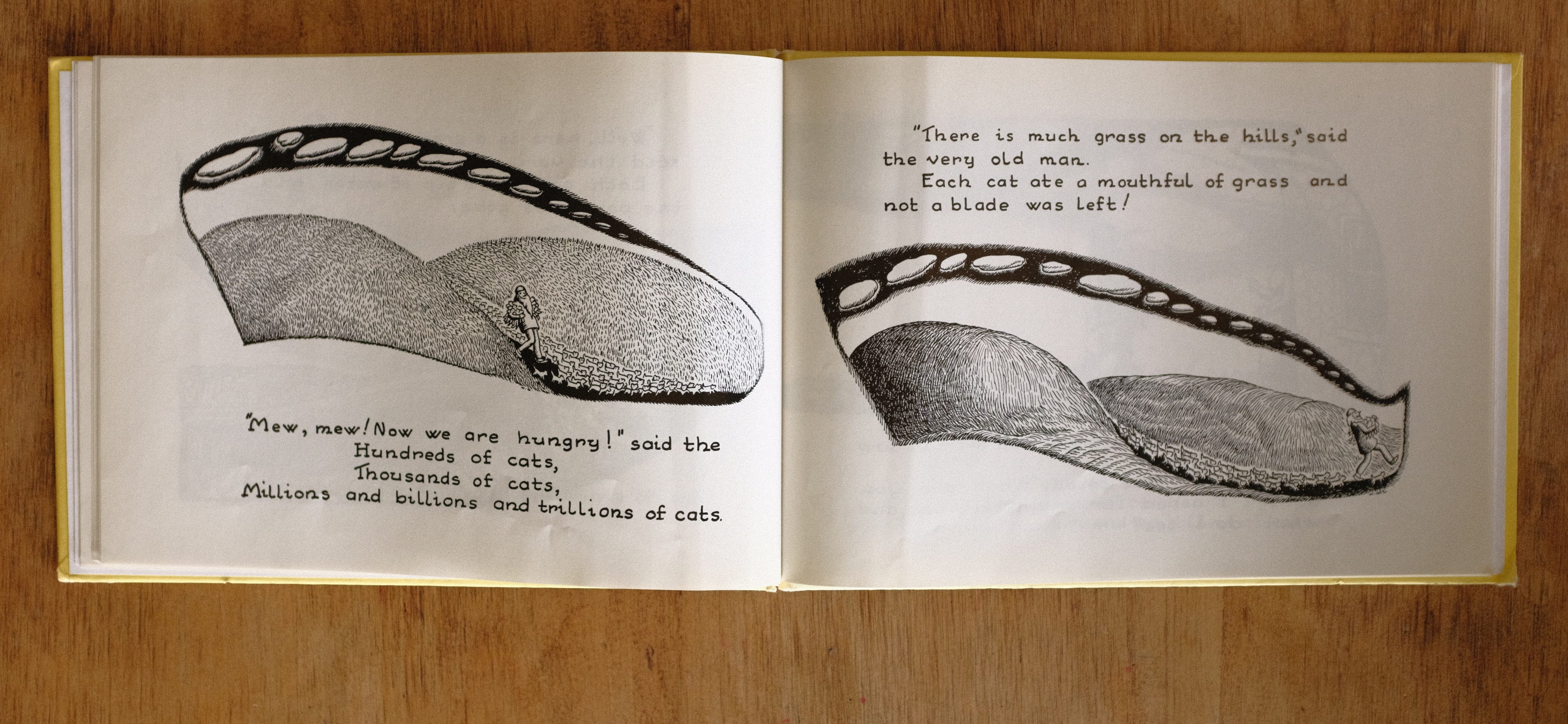

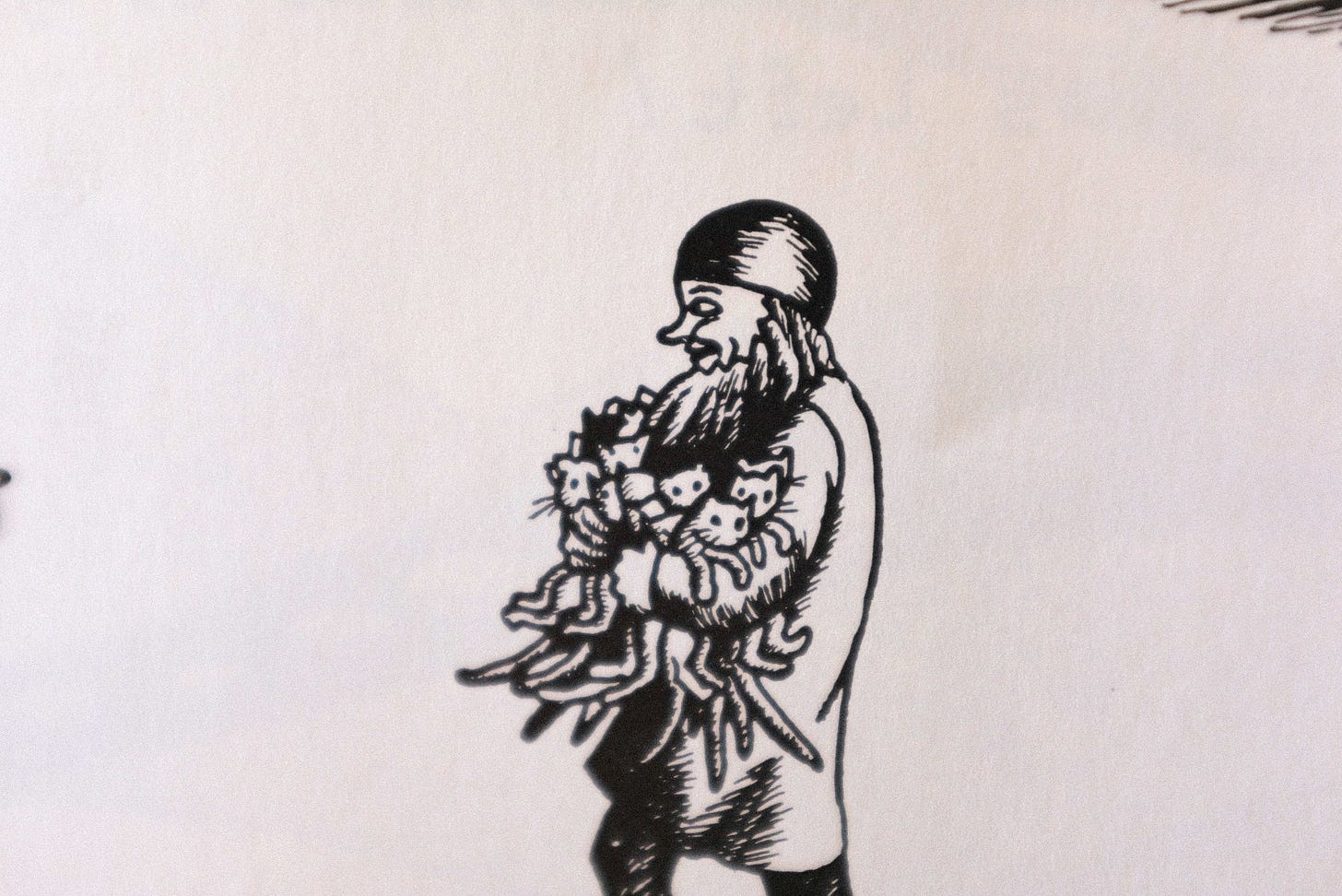

MAC: So the man takes all the cats home.

He left to get a cat.

He returns with…

millions of cats.

And the composition of this image when he arrives home emphasizes the force of all these cats (and this very foolish man) running directly into the old woman and their sweet little house.

The woman now adopts that singsong refrain we first heard from the narrator on spread three.

She says, “I asked for one little cat and what do I see?—cats here, cats there, cats and kittens everywhere, hundreds of cats, thousand of cats, millions and billions and trillions of cats.”

It’s the identical text, but it has the opposite feeling. The first time we read this, the narrator (and the man) is rejoicing. Now these same words are a lament.

The cats have become oppressive.

It's too many cats.

JON: Yeah it recontextualizes the title even. He’s so happy on the cover with all these cats but then he gets home.

MAC: On the cover he is like “Wait till she sees all these cats!”

JON: “I’m such a great guy.”

MAC: But then his face when he arrives.

JON: Just a hardened grin. “Just keep grinning. She will grin too, maybe.”

MAC: “Don’t tell her about these cats drinking an entire lake.”

JON: “You wouldn’t BELIEVE what these cats did to everything we passed on the way home. Anyway, they live here now.”

MAC: By the way, Jon, should cats eat grass?

I have never had a cat.

Are they grass eaters?

JON: When my cat eats grass it’s because there’s something in her body that she needs to expel.

MAC: Oh.

“Don’t tell her these cats’ bellies are full of grass.”

JON: And now, the best spread.

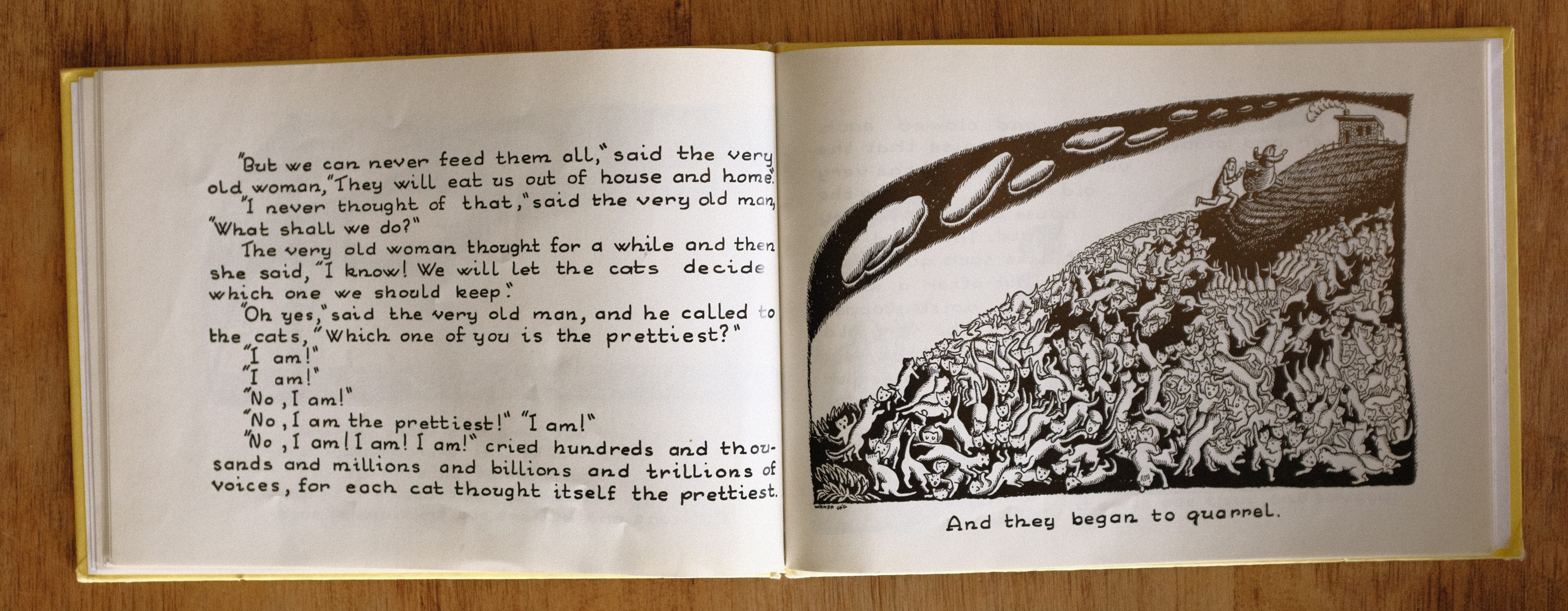

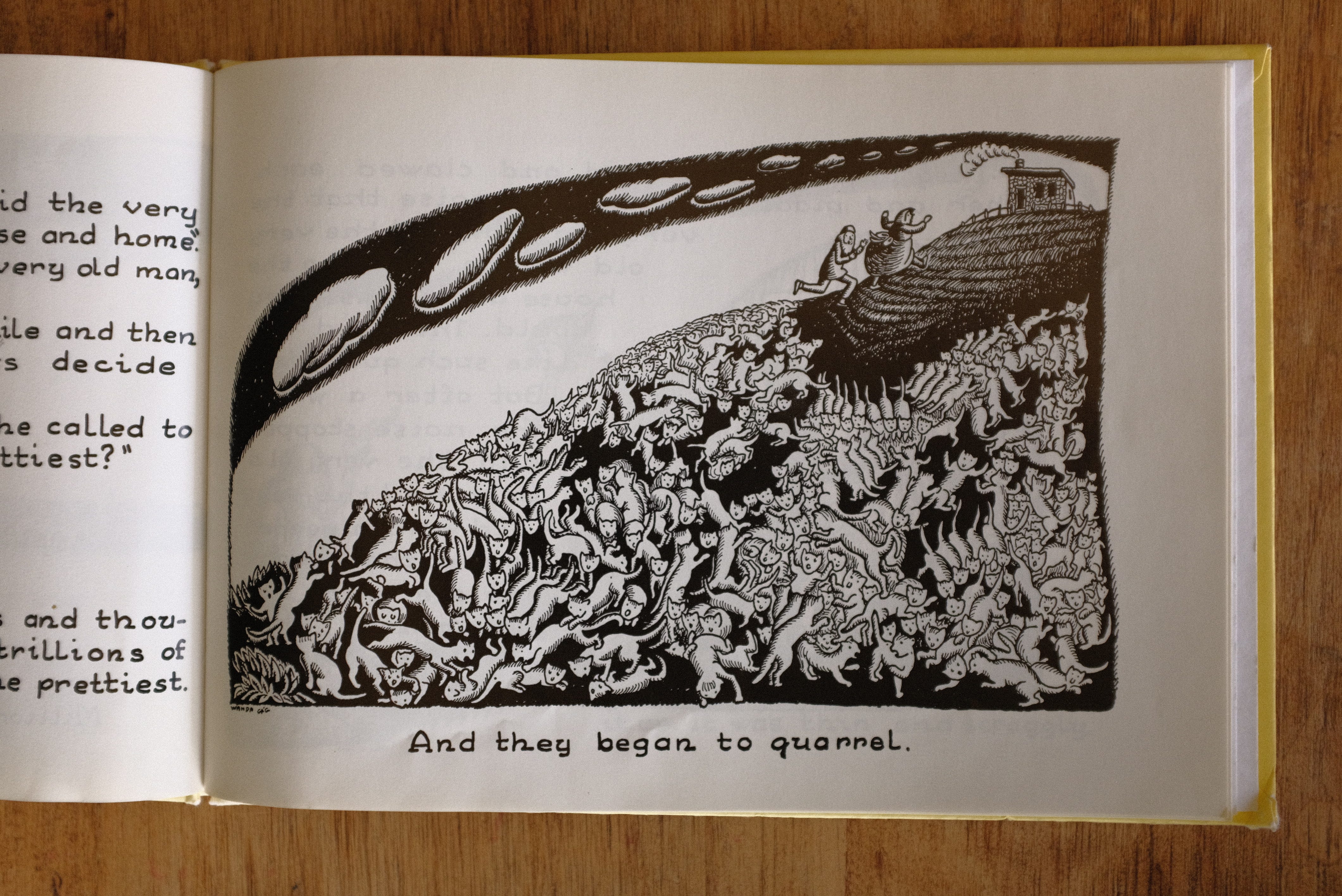

MAC: The cat fight. A scene of incredible violence. This book kills off millions of cats.

JON: Billions of cats.

MAC: Trillions of cats.

It’s a very gruesome thing in a picture book.

So Wanda Gág has a new problem to solve: How do you draw a million cats killing each other?

JON: She doesn’t. She starts to. Gág is so good at picking only the most interesting moments to draw, and letting the reader fill in the gaps between them. On this page the couple discusses the impossibility of caring for all these cats, but that’s not something any illustrator wants to draw or any reader wants to see drawn. Then the cats start to argue amongst themselves. Maybe a little more interesting. But really what the most interesting thing is showing all of them just beginning to really fight. Like, just lunging for each other.

And she draws that. It’s a monumental thing to draw.

MAC: I agree that the fight is the most interesting but I do want to linger on the arguing for one second.

Because this page, near the end, is the first time we learn that these cats can talk.

And we learn it because the man says, “Which one of you is the prettiest?”

And the cats start saying “I am!”

It gives the story a folk tale feel, but it’s a late revelation about the rules of this world that’s also just a really fun surprise.

JON: You COULD maybe argue that the cats can only understand each other. Like he might just be asking himself as much as them, but in their cat language, they all start to try and answer the question just for the group.

MAC: And look at the layout: It is a big illustration of absolute bedlam.

It looks like a Renaissance painting of hell.

JON: I even think the caption, placed where it is, recalls that. It’s captioned like a painting, with one line centered under the piece. It’s the only time she does that.

MAC: “And they began to quarrel.”

It’s a great juxtaposition.

The words fail to describe the enormity of the scene, millions of cats attacking each other. There’s a tension between the polite language and the chaos we see. The words fail to capture the “reality” shown in the illustrations. That dynamic is one of the things that makes picture books so exciting.

The man and the woman are panicking, running back to their house.

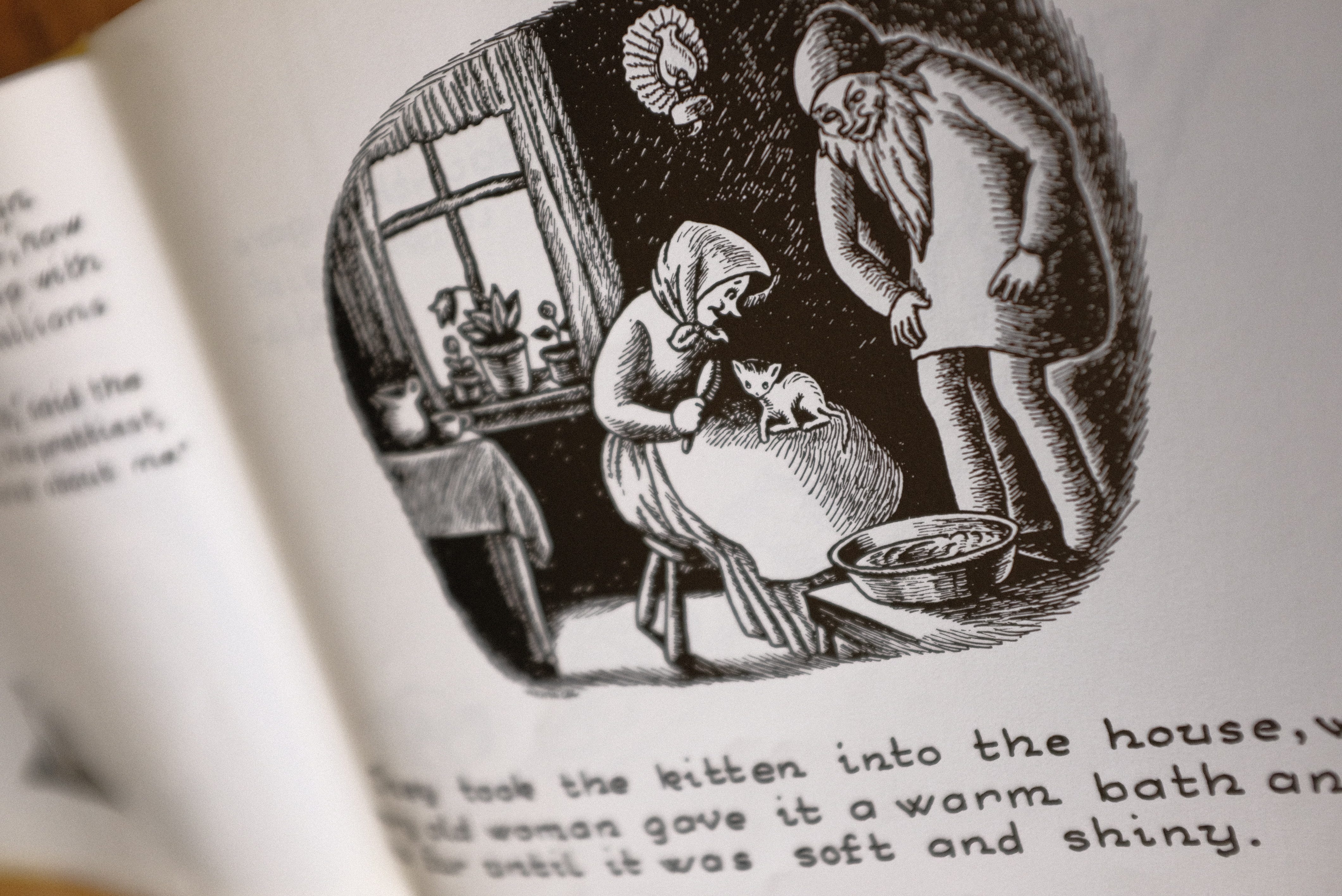

And when we turn the page, we are inside.

JON: This is my favorite drawing in the book.

MAC: It’s incredible.

The text here starts by describing something that already happened on the previous page: “They bit and scratched and clawed each other and made such great noise that the very old man and the very old woman ran into the house as fast as they could.”

—which only amplifies their panic on the previous page. They weren’t going to wait around for the narration to catch up. They had to get out of there.

And those words—“bit” and “scratched” and “clawed”—inform our mental picture of the catfight that we can no longer see on the page.

Then:

"After a while the noise stopped."

JON: The drawing here, contrasted with all of that, is so so effective. It’s the first time we've been inside their house, and it’s tidy and clean, with nice things in it. But the posing really puts this over the top. We’re reading about a battle royale outside, and he’s holding her arm gently, and pulling the soft drape back just a little bit. Everything we feel, materially, from this drawing is soft and gentle and quiet against what must be a river of cat blood outside the window.

MAC: And of course Gág doesn’t show the cat blood.

She doesn’t even show the couple’s faces.

JON: She doesn’t even actually commit to the fact that there WAS cat blood!

MAC: I wasn’t the one who brought up cat blood!

If you want there to be cat blood there is.

(You did want that.)

If you don’t, (I didn’t) that’s okay too.

You can imagine a scene exactly as awful as you want it to be.

But the cats have eaten each other up.

JON: But that’s only a theory that the characters come up with. On the facing page when they wonder what happened, the wife guesses that they must have eaten each other all up.

There aren’t a lot of competing theories, so the audience is meant to go with it, but it’s still a nice trick to get the narrator off the hook there.

MAC: Maybe the eating theory is a way of rationalizing something too awful or mysterious to actually comprehend. I mean, it only really makes sense if the little kitten that’s left over ate the second-to-last cat, who had the other 999,998 cats in its belly. And that doesn’t really seem like it would be the kitten’s deal.

JON: I kind of like that the last cat—not the kitten—ate himself up, somehow. Just got a little carried away.

MAC: That works for me. I believe this little kitten when it says “Oh, I’m just a very homely little cat. So when you asked who was the prettiest, I didn’t say anything. So nobody bothered about me.”

Which does support my theory that these cats can talk, btw.

JON: Yeah but again, it could just be that cats are intelligible only to themselves. The couple doesn’t NEED that information from the kitten to take him home. But yeah, fairy tales. I’m up for the cats talking, I don’t know why I’m going so hard here.

MAC: In any case (the humans can definitely hear and understand the kitten), I do think it’s important to note that although the kitten’s humility saves its life, it doesn’t feel like the story is advocating humility—it’s not saying, “be like this kitten and believe that you, too, are homely, and you will survive the cat apocalypse and live out the rest of your days in comfort.” It’s not a parable, it’s an original folk tale, where fate is capricious and wild things happen.

JON: Yeah, I really like that this is the first time we meet this kitten, even. A more exploitative story would’ve introduced us to this ugly kitten way back when he was picking out all the cats, to gin up our sympathies and make it land when he won the day. But this book doesn’t do that.

MAC: By the way, it does feel like there’s something very smart in the way that Gág designed all those cats we meet on the hill, where they are cute enough that we enjoy meeting them but not so fully realized that we feel revulsion about their demise.

JON: RIGHT. They remain anonymous, which gives us permission to be ok with all of them dying.

MAC: And this little cutie is not anonymous—

Gág draws the kitten differently and isolates it on the page, surrounded by lots of white space, so it looks vulnerable and alone and individually distinct.

JON: I went to look if it was the first time she drew pupils on one of the cats, cause that would be a cool thing for me to notice and call out, but she put pupils on one of the anonymous cats at the start :(

MAC: RIP that one cat with the pupils.

JON: So expressive.

MAC: I really loved that cat...

Anyway, the couple takes the kitten home and the kitten has a glow-up and they live happily ever after.

Jon, what do you make of seeing the couple as young and beautiful in those portraits on the wall here, on the second to last page (and final spread, since we’ll only get a single page at the end)?

JON: It’s hard to pin down, exactly, but it’s a BIG deal, somehow. It gets into the larger question at the start of the book. Gág never says “they couldn’t have children,” she only says “they were so very lonely” and they are old enough now that you could believe that if they did have children, the children have grown up and gone. But either way, they miss it.

The portraits suggest that the young kitten in the house makes them feel young again. But they also get us more invested in the couple. Look at how long they have been together. They’re so great. We love them. The book is about them—the titular cats remain anonymous, except for this last one. The picture book is really a description of a married couple who love each other.

MAC: Yeah, seeing them here, as young people, connected by this lush fruit garland—it’s very touching.

JON: Again, they have a nice house. Gág could’ve gone hard on sympathy here too, made them visibly poor and stuff. But they have made a nice life even before the cat stuff, and they will give this cat a nice life inside it.

MAC: And then a great last page:

No words, just—

MAC: Think about how that picture functions as an ending, how whatever feeling or satisfaction it engenders is different from a well-wrought last sentence.

JON: What a book.

“RIP that one cat with the pupils.” I just spat my coffee out 😂

Great conversation, love to learn what you two see when you look at these books. I wonder about the clouds as well. Special care seems to be put into making sure they have their place on the page. It also makes me think of the tiny house on top of a rolling hill, that's also a recurring scene in picture books. Her line work all over is really great, for sure an influence on Crumb and the like.