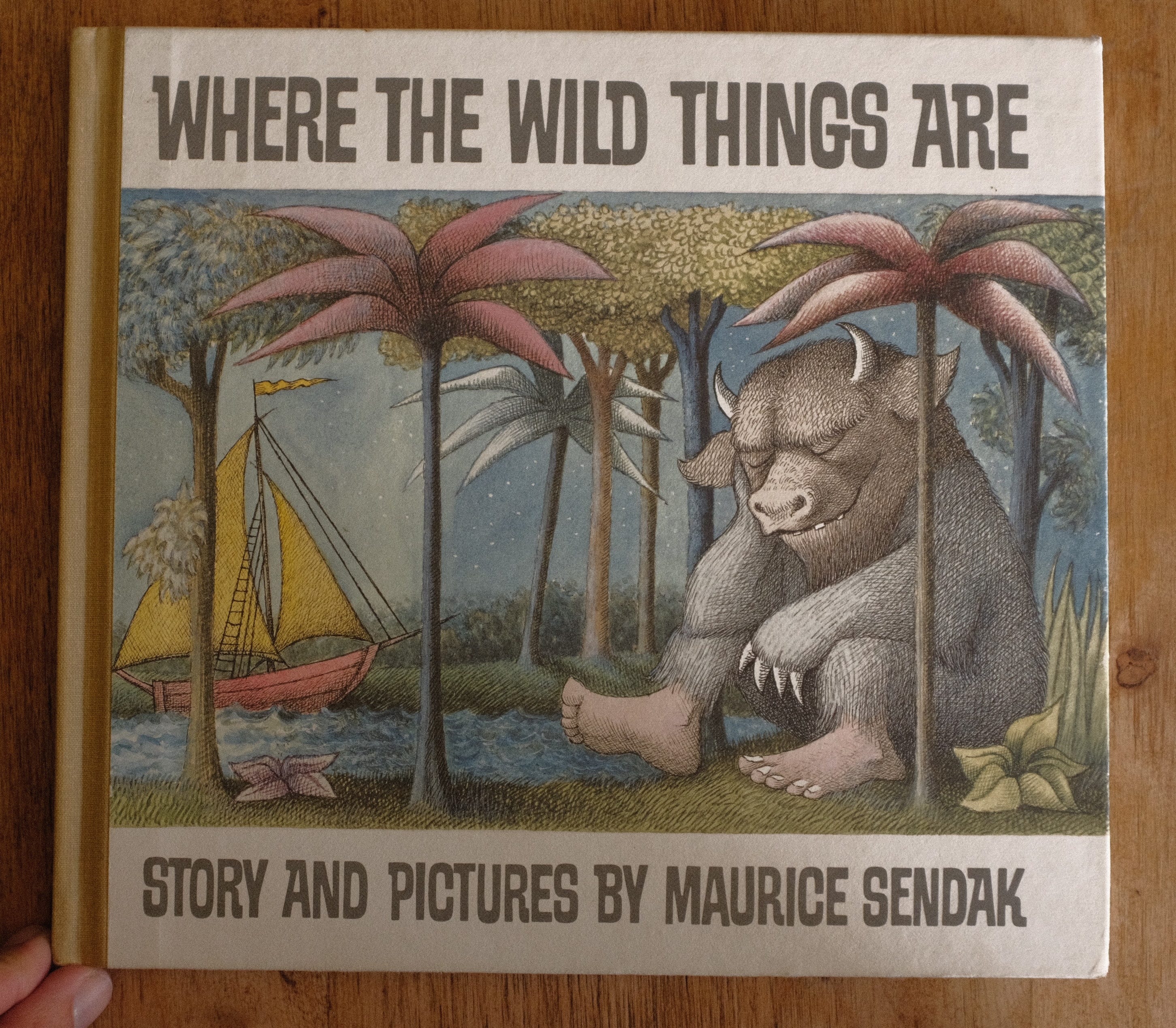

Where the Wild Things Are

Jon and Mac consider: annoying Sendak quotes, Mac's high-school bully, gutter talk, a photo of Maurice looking good in a white tee, ambiguity, repression, and grace

Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are was published in 1963 and won the Caldecott Medal, the USA’s highest honor for picture books. You can’t really overstate this book’s importance to the history of children’s literature—or to American culture. One example: Each year, at the annual White House Easter Egg Roll, President Barack Obama read a picture book to children, and he chose Where the Wild Things Are every single time. (This despite the abundance of exciting new picture books published during the his presidency, including a couple that were beautiful statements of US-Canadian cooperation, a cornerstone of Obama foreign policy.)

Where the Wild Things Are has sold more than 19 million copies worldwide and has been translated into more than 40 languages. There’s a famous Sendak quote people love (but which has always annoyed me) from an appearance on the Colbert Report near the end of his life: “I don’t write for children. I write, and somebody says ‘it’s for children.’” Contrariwise, in his 1964 speech accepting the Caldecott, Sendak said, “Where the Wild Things Are wasn’t meant to please everyone. Only children.”

Jon and I had the following conversation over text. —Mac

MAC: Hi Jon.

JON: Hi Mac.

MAC: Today we are “looking at”

(get it?)

JON: (not yet)

MAC: Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak.

JON: We’re going for it.

MAC: Finally, we’re going to figure out why this book is good.

MAC: You’re welcome, Maurice.

JON: Yeah, for a lot of people this book is The Book, when it comes to picture books. Would you say it’s your The Book?

MAC: OK, so I loved this book when I was a kid — the copy we’re looking at today is from 1985, when I was three years old, and the flyleaf is inscribed: “To Mac from Mommy, this is one of your favorite stories.”

But later I think I got put off by its cultural omnipresence.

There was this guy who bullied me in high school who wore a Where the Wild Things Are shirt a lot. He was sort of a precursor to the type of guy who would put Where the Wild Things Are as his favorite book on his MySpace profile. His name was Nate. I don’t think he subscribes to our Substack.

JON: Yeah, I remember clearly seeing it in the library at school, and it feeling like this objective, definitive thing that looked like it had always existed.

MAC: Where the Wild Things Are is ubiquitous. And when a book becomes ubiquitous it can seem ordinary. But this is not an ordinary book.

JON: My memory of it is almost as more of an object than a story. I was scared of it.

MAC: It’s about a tantrum and its aftermath. Let’s look at the first spread.

(by the way, a spread is what you call the two pages of a picture book that lie open)

(I know you know what a spread is, Jon)

JON: (always good to be reminded)

MAC: (I am writing this for any of our wonderful subscribers who might want to know some of our cool technical terminology)

JON: (stick around everyone)

MAC: The book opens on violence and destruction. Max is scowling. He is putting a hole in the plaster. That teddy bear is dangling very disturbingly from the coat hanger.

The text is on the left page and the image is on the right. It’s a very traditional way to lay out a picture book spread. This formality of the design contrasts with the emotional register of the picture.

JON: Yeah, the formal design of this page, and actually the rest of the book, is, on its own, a huge deal. The white space on this first page, how small the illustration is on the page with all that white space around it, is serving to cramp Max in.

MAC: Yeah, right now he is contained, even constrained.

JON: It’s stressing him, and us, out. On purpose.

JON: The white space around the illustration here has shrunk a bit. It’s opening up the image, which fits the more action-y moment it’s portraying, but is also setting up a sequential idea where that white space will continue to shrink as the book goes on.

MAC: And maybe it’s obvious, but the white space shrinking means the image is growing. As Max is getting wilder, the pictures are getting bigger.

JON: Incidentally, the choice to have Max running/facing the opposite way than he was in the previous spread here is a nice way to give the feeling that he’s just crisscrossing the house causing trouble. If he’d been going to the right here, it might look like he purposefully ended up in his room on the next page, but this way you get the feeling he was stopped in his tracks and turned around against his will.

MAC: He is chasing a dog with a fork, presumably to eat it.

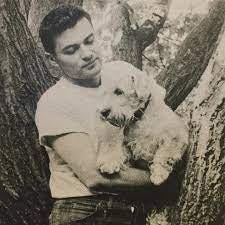

That dog, by the way, looks a lot like Maurice Sendak’s dog, Jennie.

JON: Man that’s a great dog.

MAC: And a great t-shirt.

JON: OK, next spread.

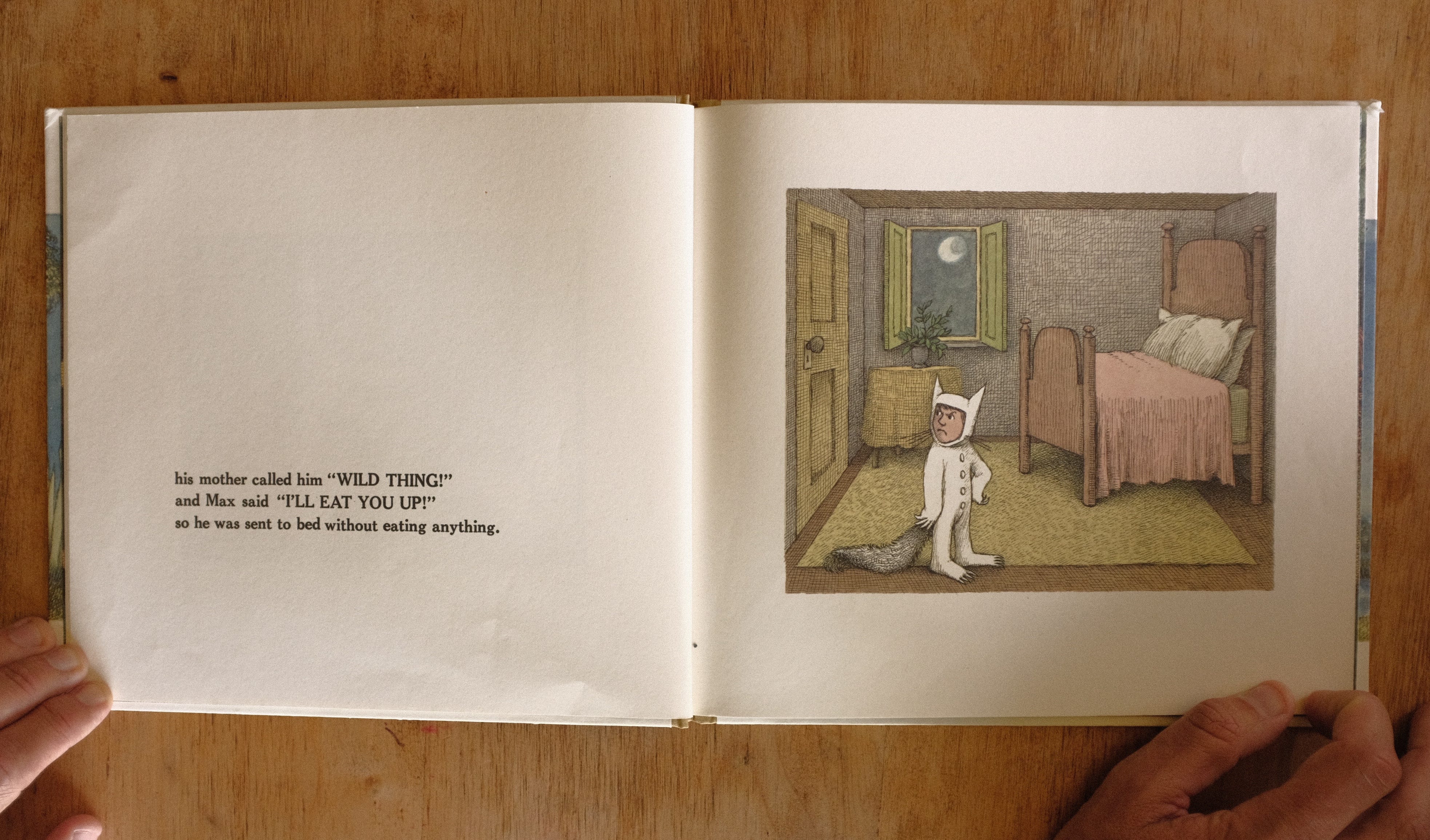

JON: The picture has grown here, compositionally, but also what a massive amount of implication this picture has. We have skipped a big moment. Since the previous spread, Max’s mother has decided she’s had it, dragged him upstairs, thrown him in there, and slammed the door. Think about what a weaker thing it would’ve been to have shown that over like, two more spreads instead of skipping to this moment.

MAC: In a picture book, the text and illustrations both tell the story, but sometimes one or the other is doing the heavy work. As Sendak put it, “Words are left out — but the picture says it. Pictures are left out, but the word says it.” This dance between text and image is one of the picture book’s great formal marvels.

Here, one of the most important moments in the book happens “offscreen.” It’s not shown, but we learn about it from the words. Max and his mother lose their tempers. (For the record, his mother loses hers first.) She calls him “WILD THING!” And then Max threatens to eat his mom, which is the worst thing he’s done yet (sorry, Jennie).

These two outbursts are the only time capitalization is used this way in the book — as the story moves forward, it will get very noisy, but we will never see all caps again. And Sendak generally is a restrained writer — this was a big choice. This fight was really bad.

JON: Take a look at Max’s room. This is a kid who is dressing up as an animal chasing the dog with a fork. If he had any agency over what his room looked like, it would probably not look like this. Sendak knew what a fun room looks like — any picture of his own house and studio is full of toys and stuff.

This room looks like Max is staying at a bed and breakfast. It’s dry and boring and cramped. Not only are we getting a look at what his relationship is like with his mom, we’re seeing how she runs the house. No wonder this kid is about to grow a forest in here.

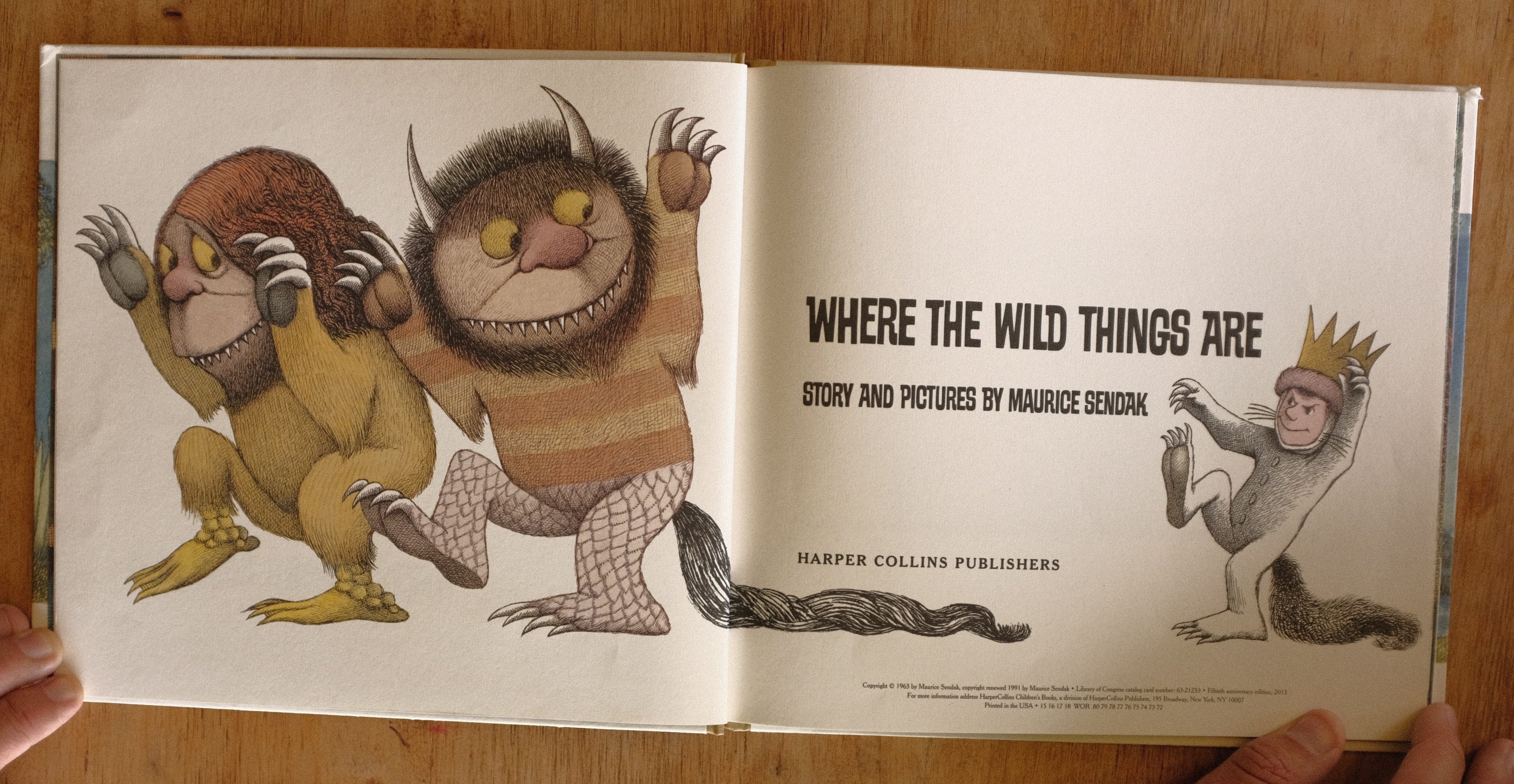

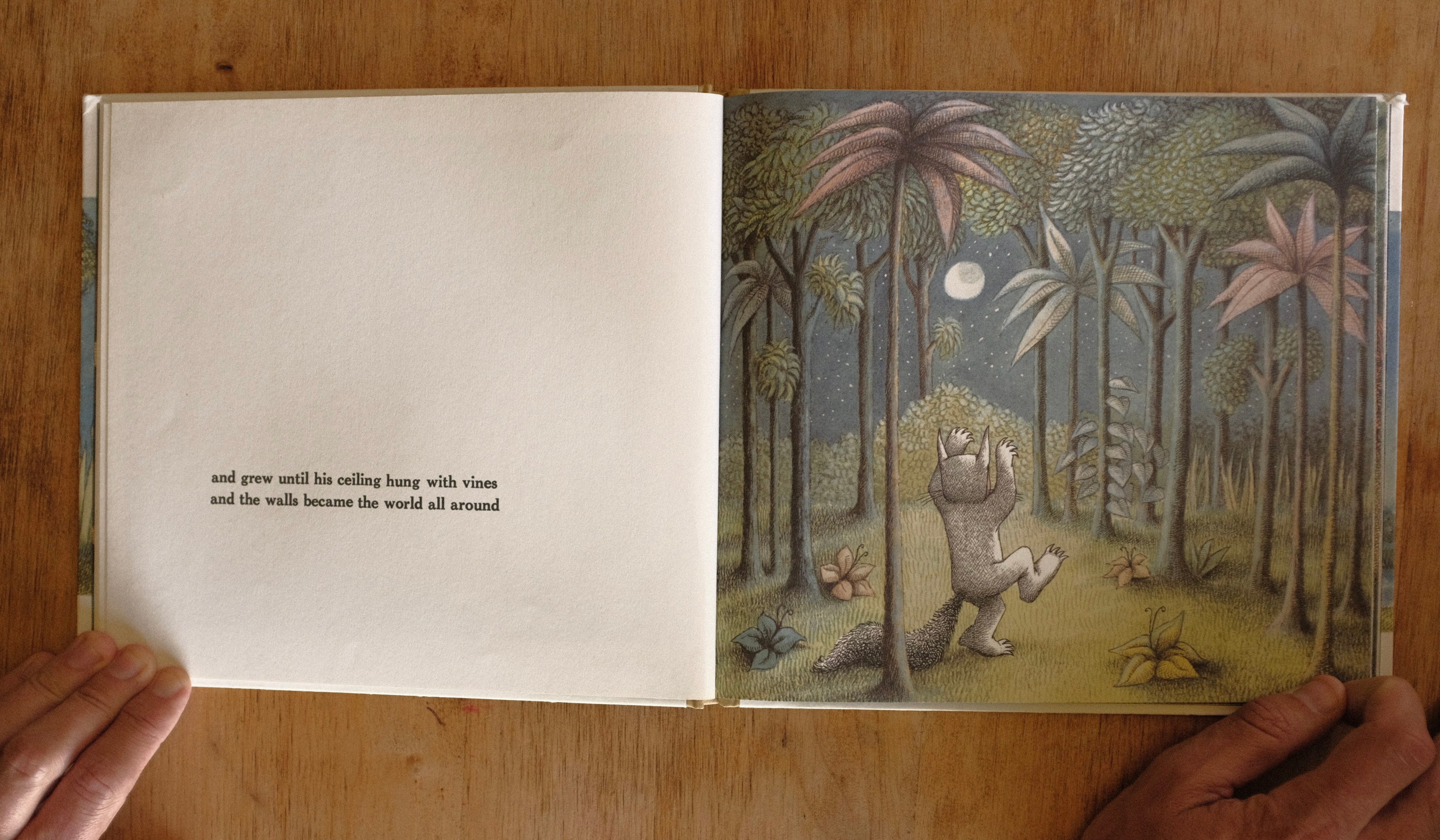

MAC: A forest grows in Max’s room, and the illustrations continue to grow until there is no white space — a “full bleed illustration.”

And then:

The illustration crosses the gutter!

(The gutter is the line right in the middle of the two pages of a spread!)

The pictures are invading the words!

JON: It’s a great trick. Another thing here is how shallow this all feels, spatially. Sendak is totally capable of drawing distance and space, but he’s deliberately squashing it here. It’s not supposed to look real. It feels like a stage.

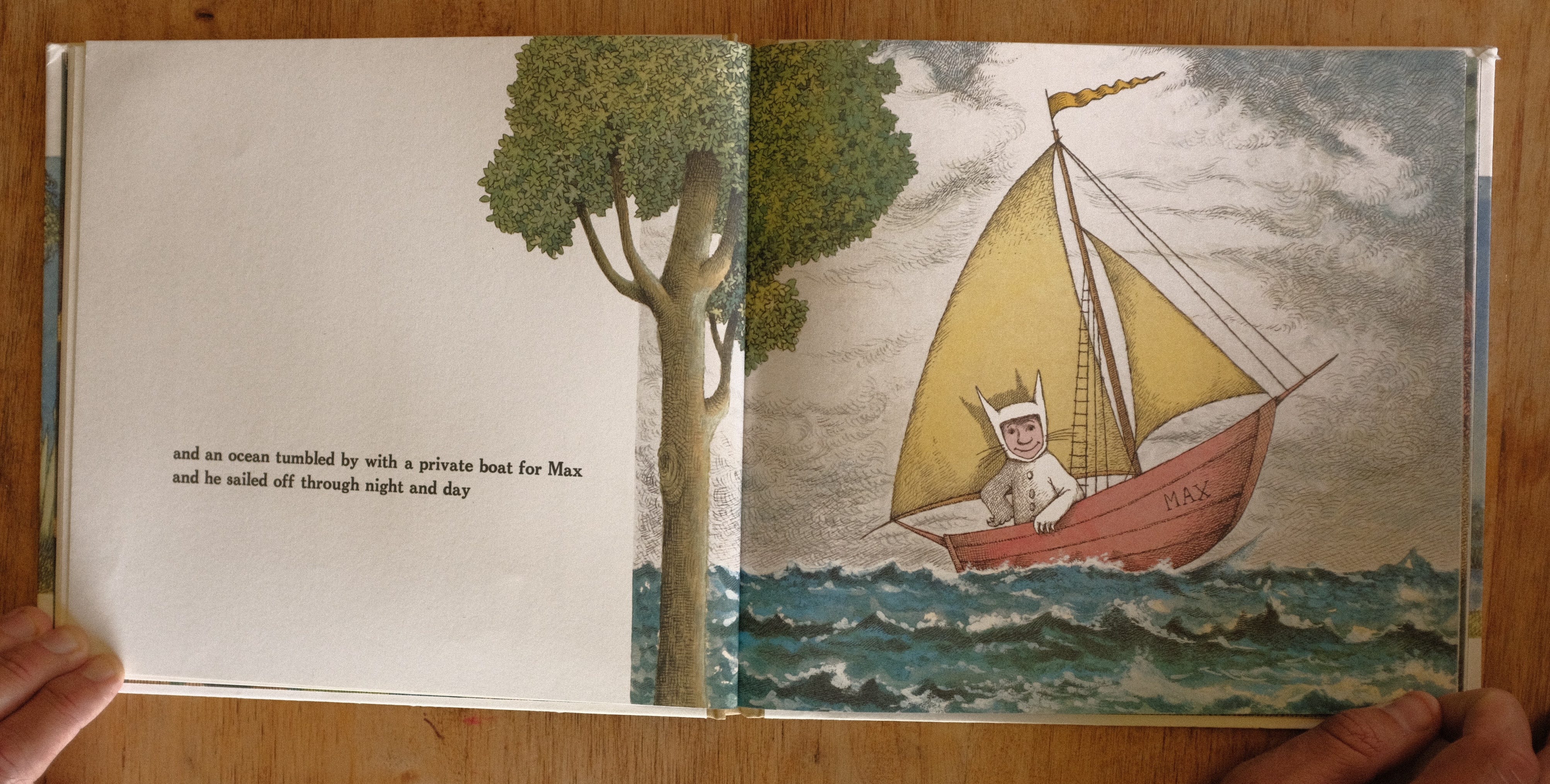

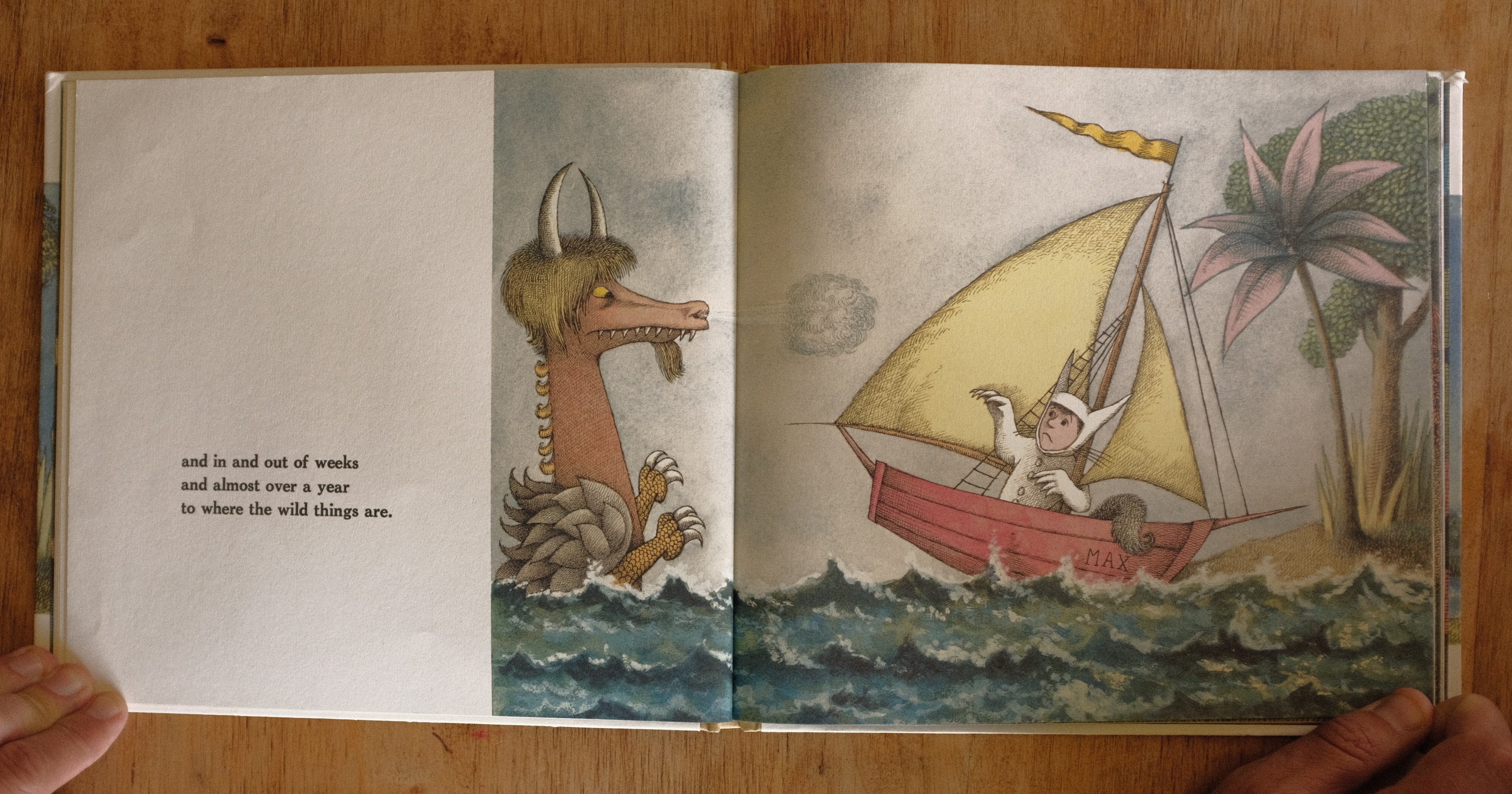

MAC: Sendak warps both space and time — Max sails “through night and day and in and out of weeks and almost over a year . . .”

“. . . to where the wild things are.”

JON: There’s a period in the writing ending a sentence on this page, and it’s only the second period of the whole book. We have been introduced to Max and his household dynamic, shut him up in his room and had him escape to cross years of travel to an exotic island, and we’re only two sentences in.

MAC: It took you two sentences just to say that!

JON: I submit that I got just as much accomplished.

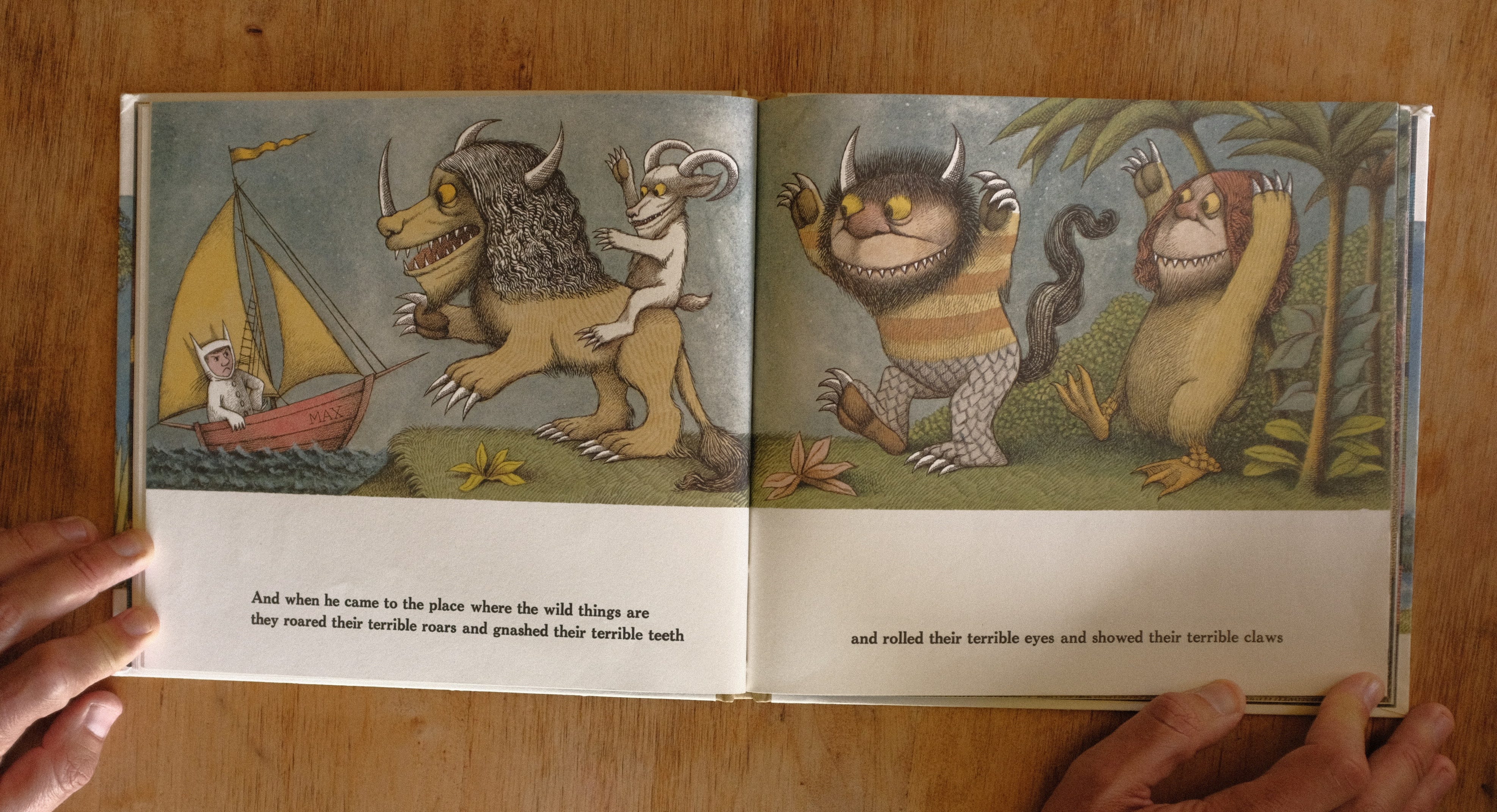

MAC: When Max arrives on the island, the design of the book changes again.

Now we have a full-bleed illustration that runs across the entirety of the spread, both pages, and the words go in a white bar at the bottom.

As Max is crowned “king of all wild things” the pictures get even bigger, and that white bar shrinks, until we come to maybe the most famous sentence in any picture book: “‘And now,’ cried Max, ‘let the wild rumpus start.’” The rumpus is three glorious full-bleed, two-page illustrations. The white space is gone. There are no words.

(These are called “wordless spreads.”)

JON: After all, what would you write? A bunch of sounds? It’s so much louder this way.

MAC: And then, suddenly, the rumpus is over, and the words are back.

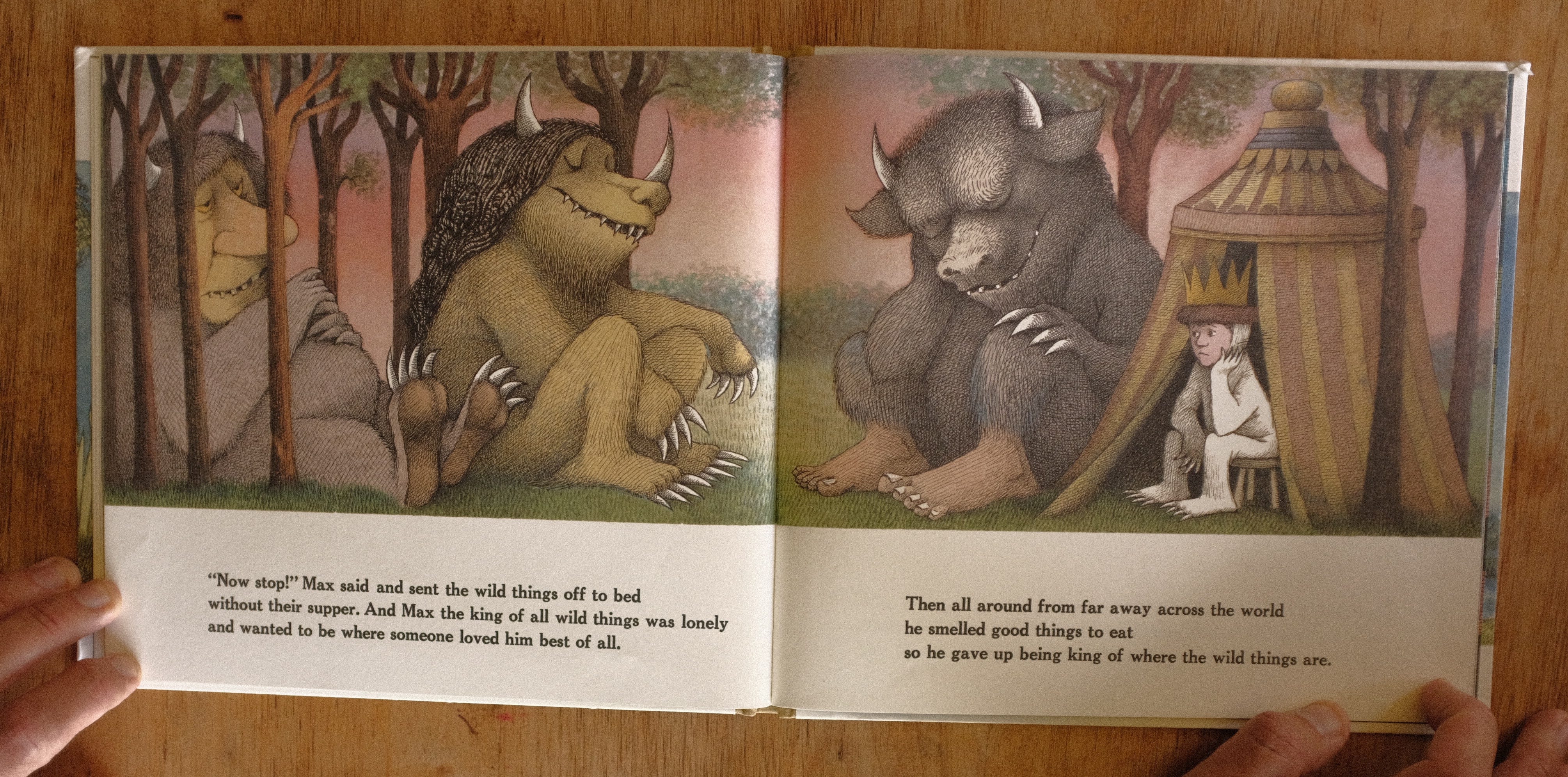

This is another huge moment in the book. There’s a lot going on and there’s a ton of ambiguity here, and it’s worth spending some time on this spread.

Max sends the wild things to bed before his supper. He’s doing to them what his mom did to him.

(Though the wild things didn't do anything wrong.)

And he decides to go home.

We don’t know why Max changes, exactly. The text says that he’s lonely.

JON: I have a theory on this!

MAC: HOLD ON.

JON: HURRY UP.

MAC: I AM SETTING YOU UP FOR YOUR THEORY.

There’s a contrast suggested between “where the wild things are” and “where someone loved him best of all,” which use the same grammatical construction.

But, Jon, I think you have a theory on this.

JON: OK. This drawing of Max, to my mind, is the most nuanced drawing in the book. So far we’ve seen him look almost exaggerated in his emotions the whole time. He’s been loud, angry, very happy, yelling, etc. He’s been like a cartoon of a kid. This drawing of him looks almost adult.

MAC: Yeah, now “words are left out—but the picture says it.” What's Max feeling here? Disappointment? Boredom? Regret? Part of the beauty of a picture book is that it allows you to talk about things impossible to describe with only words.

JON: He looks, to me, like how I look when I’ve sent my kids to their room and I don’t really love how the exchange went. They’re in there, and I’m in the kitchen, and I sit down and I look like Max does here.

MAC: This book is about Max and his mom, but we never see her. She doesn’t appear in any of the illustrations. Except maybe this one, because Max has become his mom — he has sent the wild things to bed without supper. And we might imagine that, right now, she is back home, resting her chin in her hand, wearing this very same expression.

JON: They’re like E.T. and Elliot. They’re E.T.ing.

MAC: There's so much pathos in his expression, but ambiguity too, and each reader’s reaction to this scene will be very personal. We get to decide why Max goes home.

(cuz right after this Max goes home)

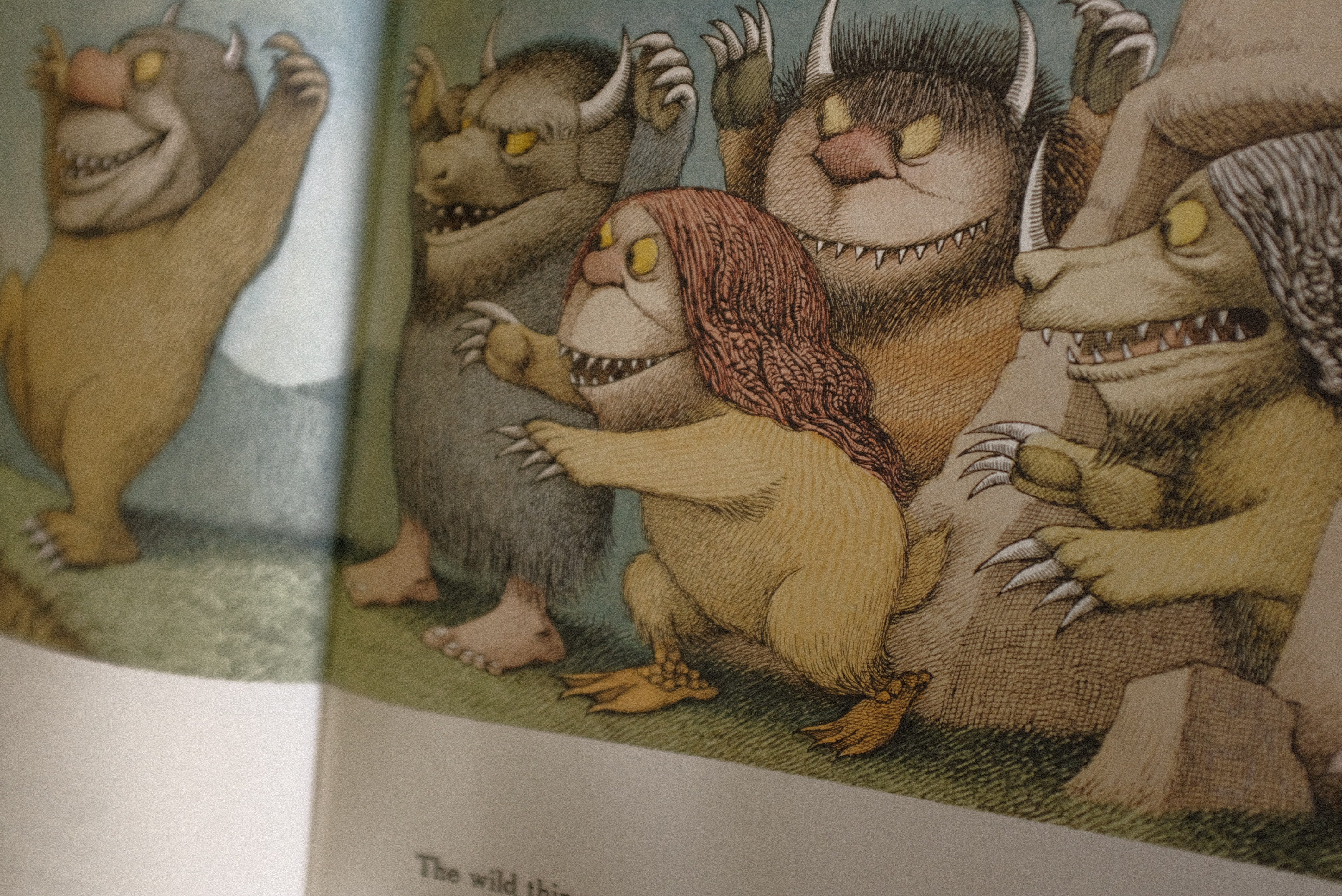

JON: So he’s going home, and I remember as a kid this being the spread I puzzled over the most. I don’t know how the wild things are feeling here. He’s leaving, and happy, but they’re still doing their thing. The text is saying they’re sad about it, but the picture doesn't have them looking that way. It’s almost like they’re already reverting back to just mindlessly roaring and waving around. They don’t seem to have any discernible emotion here. I used to stare at this one. It’s still mysterious to me.

MAC: Now “eating you up” is no longer a threat, but a declaration of love (albeit a threatening one).

Max sails off toward home, and the language repeats — “in and out of days,” etc. — and the illustrations shrink down and the white space grows and Max arrives back in “his very own room.”

We are back in the real world, and back to our formal layout: words on the left page, a picture on the right, but now the illustration is full-bleed.

Max’s world has grown to fill the page.

JON: Yeah, it’s even neat to see the slight difference in how he drew the room here, as opposed to when we first see it before he leaves. The door on the left is breaking frame now, we’re slightly tighter in. When we first saw it, we saw more wall on all sides, like this box we were stuck in. We’re still in a one-point perspective at the end here, but everything is a little more relaxed now. He’s stable.

MAC: Where the Wild Things Are of course can be read as a “psychological book” about a kid “working out his emotions” by using “the power of his imagination.” But as someone who has always hated it-was-all-a-dream endings — and especially hated them as a kid — I am excited about a wonderfully confounding detail out Max’s window. The moon is in a different phase than on the night he left. It’s full now.

JON: I think one thing we might forget because of how much this book is read and how well we know it, is actually how stressful it is to think that he was gone for so long. I was super stressed by that the whole time. And Sendak sort of tries to take care of that, with supper being there, and the visual fakeness of the island world throughout, to hint that it was all in Max’s head, but he also does the moon thing to say it was real! One of the things that made Sendak so good at this, I think, was his comfort with contradiction, and ambiguity. He knew that’s where we all live, where kids live, and where he could leave us. It’s real and it isn’t.

MAC: Yes! The moon splits the book into two realities: the reality of the pictures and the reality of the words. Because the pictures tell us that a lot of time has passed. And the words tell us that not much time is passed at all:

“he found his supper waiting for him,”

and here comes a startling page turn, leading to Sendak’s perfect finish:

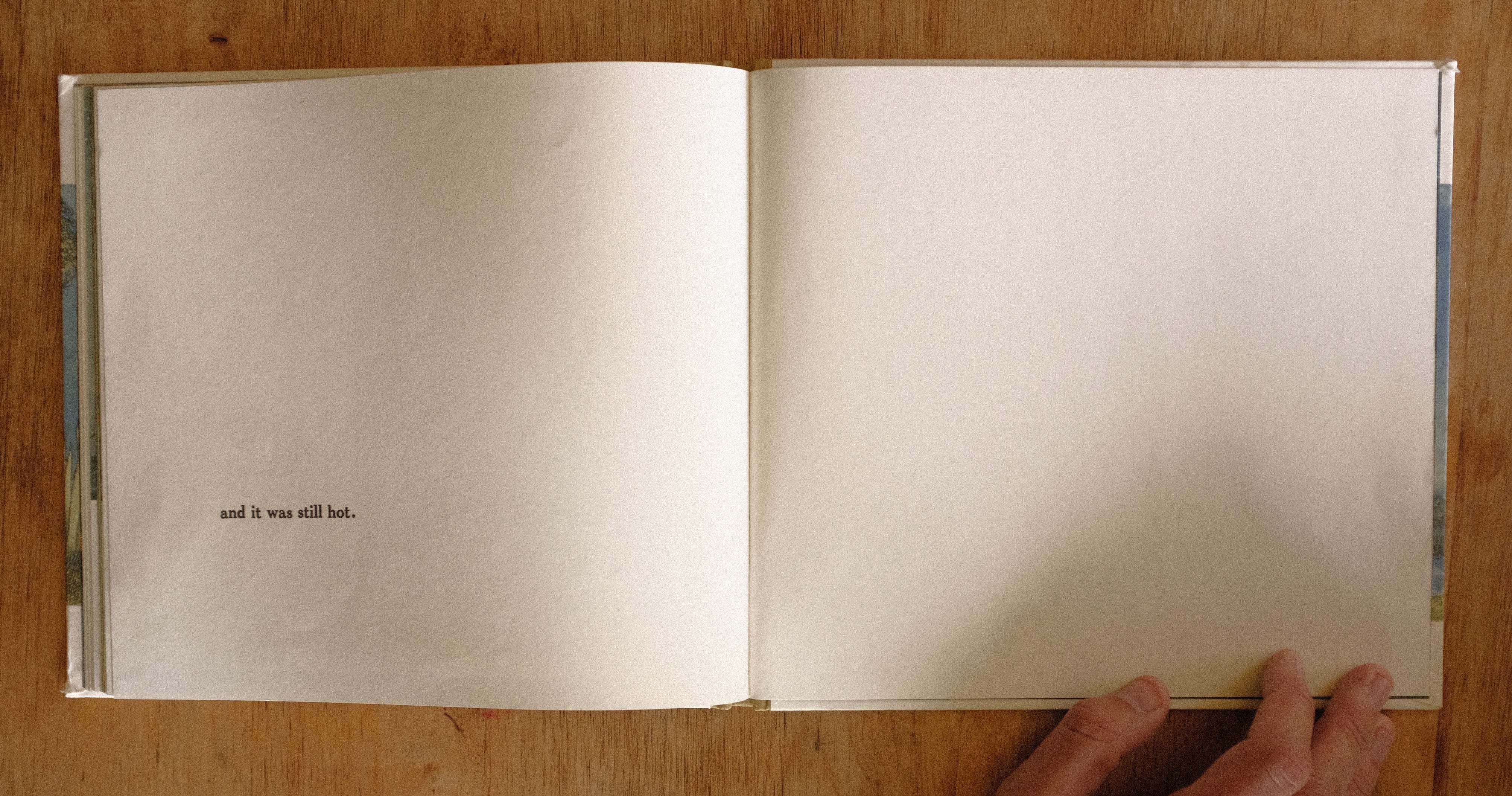

“and it was still hot.”

Jon, what do you make of the fact that there is no illustration here?

It’s just five words and white space.

JON: Well. Like you said, we haven’t seen the mom the whole book. But this is as close as we come to seeing her live on the page, I think. We have the ET page earlier, but this page, if it had a picture, should probably be her in the kitchen, smiling, now that she’s made things right. She’s forgiven him, both for the behavior that evening and for leaving, if he did leave (another big question is, if he WAS always in the room, did she bring it in and see him? was he gone? she left it there like he was gone!).

MAC: (I used to think about this exact question a lot when I was kid!)

JON: Sendak, to me, always seemed almost overwhelmed in the work. He was so raw and so emotional, I almost couldn’t take it, and it’s what scared me about his books. It’s just a theory, but if this page is about his mother, maybe he can’t even show her. It’s too much. The best he can do is leave it blank. And of course the book is better for the omission.

MAC: It’s worth pointing out that Max never apologizes. If he changed on that island, we don’t know how or why. And he doesn’t have to make amends in order to get his dinner (and his mother doesn’t make amends either, even though she clearly also felt bad). It’s so moving. And it’s also radical — there’s always been a strong and widespread belief that children’s books should moralize and that the characters in them should model good behavior. But Max doesn’t need to change who he is to be deserving of his mother’s love, or worthy of being the hero of a book.

JON: Yeah, the final thing just seems to be establishing a state of grace.

My God, the moon! I truly never noticed in hundreds of readings.

My boys and I always enjoyed observing the slight changes you two made to the environment upon Sam & Dave’s “return” from digging their hole… the subtle changes in cat collar color, in flowers, and in weather vane animals indicate that they didn’t entirely arrive back to their original place of departure… it wasn’t a dream… things have changed…

I had noticed the dinner on the last picture in Wild Things, and the change of bedroom perspective/ size, but I never noticed the difference in the moon!

This was a really lovely read.

I look forward to more!