Good Books for Bad Children

Plus our power ranking of children's literature's greatest Ursulas

Ursula Nordstrom, the legendary editor and director of Harper’s Department of Books for Boys and Girls from 1940–1973, was probably the most consequential figure in the history of American children’s literature.

She published Goodnight Moon, Where the Wild Things Are, Charlotte’s Web, Harriet the Spy, Harold and the Purple Crayon, The Giving Tree, Freaky Friday, A Tree Is Nice, Stevie, Bedtime for Frances, How We Read: A to Z, Crictor, the Little Bear books, and many other classics. After her death in 1988, Maurice Sendak told The New York Times, “Ursula Nordstrom transformed the American children's book into a genuine art form.” (The whole obituary is worth reading.) Nordstrom famously described her job as publishing “good books for bad children.”

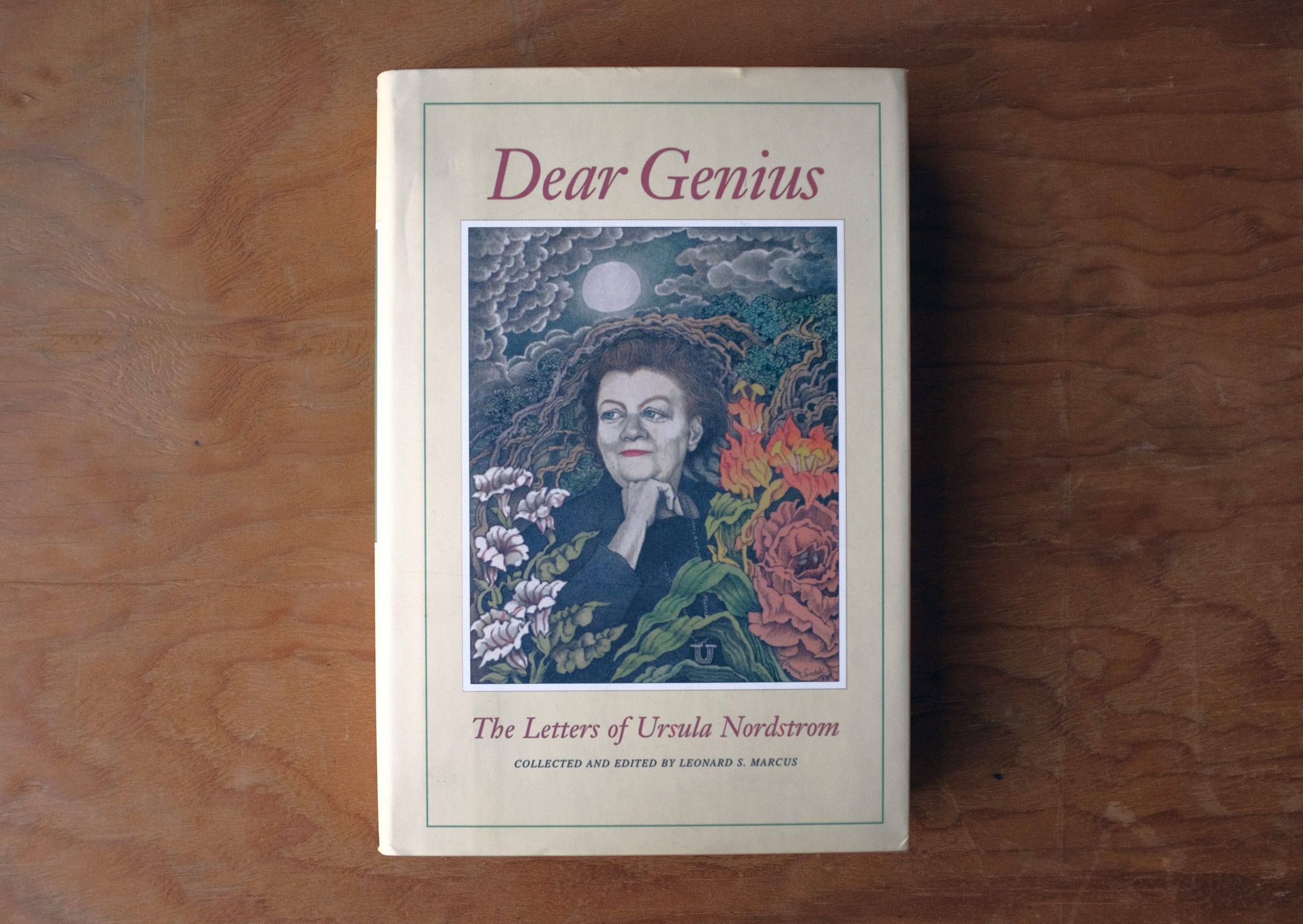

Leonard Marcus’s collection of Nordstrom’s letters, Dear Genius (titled after her frequent way of addressing correspondence to the authors and illustrators she worked with), is essential for anyone interested in picture books.

Nordstrom coined the phrase “good books for bad in children” in a feisty reply to Meindert DeJong, a Dutch-American writer who would one day win the Newbery Medal and Hans Christian Anderson Prize. But in 1953, DeJong was discouraged. He wasn’t making money as a children’s author. And he’d just seen an advertisement for the Book-of-the-Month Club trumpeting that the “vast majority” of Random House’s Landmark Books for children were by “serious adult writers.”

Nordstrom was ticked off:

Dear Mick:

…

That BOMC crack about juveniles and the Landmark Books' has irritated everyone thoroughly but it is so silly that it shouldn’t bother any of us. It certainly shouldn't bother a writer like you, or even an editor like me. I get absolutely wild some days, thinking of you keeping that darn job in that church, so you can write your wonderful books. But you are praising the Lord in your own fashion, Mick, as even I am doing in my own modest, harassed, untalented fashion. And I can assure you that you are a happier and more successful human being than most of the authors who hack out those machine-made, tailored to order, bloodless Landmark Books. But why am I telling you all this, Gustave, when you know it already? I'm giving myself a pep talk I guess, because even an editor gets discouraged some-times. You wrote me “I do know that if you depart from the usual run the librarians and teachers who control the juvenile field are scared” and I guess that is true some of the time but not all of the time. I haven’t any author like Meindert DeJong on this list but some of the other books we’ve been publishing are sort of unusual, and off-beat, and I KNOW the children would love and recognize them, but they come up against some influential and unimaginative and thoroughly grown-up and finished and rigid adults. Some mediocre ladies in influential positions are actually embarrassed by an unusual book and so prefer the old familiar stuff which doesn't embarrass them and also doesn't give the child one slight inkling of beauty and reality. This is most discouraging to a creative writer, like you, and also to a hardworking and devoted editor like me. I love most of my editor colleagues but I must confess that I get a little depressed and sad when some of their neat little items about a little girl in old Newburyport during the War of 1812 gets [sic] adopted by a Reading Circle.

Well, you couldn’t do anything else and neither could I. Did I ever tell you that several years ago, after the Harper management saw that I could publish children’s books successfully, I was taken out to luncheon and offered, with great ceremony, the opportunity to be an editor in the adult department? The implication, of course, was that since I had learned to publish books for children with considerable success perhaps I was now ready to move along (or up) to the adult field. I almost pushed the luncheon table into the lap of the pompous gentleman opposite me and then explained kindly that publishing children’s books was what I did, that I couldn’t possibly be interested in books for dead dull finished adults, and thank you very much but I had to get back to my desk to publish some more good books for bad children.

And maybe when you finally do get some money from your wonderful books for children you'll be able to afford some time and write a book for adults, but I doubt that you'll love doing it as much as you do your books for children. I want money for you, God knows. But I absolutely believe that sooner or later you will make money with your children’s books. In the meantime what you are doing out there in Grand Rapids really amounts to giving the children a present. I haven’t written any of this because I think you are discouraged. Your letter made it clear that you weren’t and that you’ll always want to write children’s books. I just felt like spending some time writing to my dear Mick. And I’ve been a little blue and discouraged myself, I’m ashamed to say, and that is silly. “Discouragement is disenchanted egotism,” as some man said . . .

It is disgusting to realize that I am so egotistic about the sort of books I pick out to publish for children.

Anyhow, the walls will come tumbling down one of these days. The Ruth Krauss Bears absolutely horrified some people but they’ve finally had to admit that the children simply love it and Ruth Krauss is gradually finding more and more acceptance and her books are selling better. It will happen with you, too. Meanwhile, dear, we still have each other and you are a great comfort to me, rivers of water in a dry place.

If Shadrach doesn’t win the Newbery surely Hurry Home Candy ought to, if Miss Powers is as right as she usually is.

I’ve written Sendak to say that of course you and I want him to illustrate Hurry Home. He is finishing one book, then has to do one for another publisher (everyone wants him now, since the Marcel Aymé book and A Hole Is to Dig) and then he’s going abroad in June. But I know he will do the drawings if he possibly can. If he says he can’t possibly fit it in to this horribly crowded schedule I’ll just have to find someone who can draw exactly like him! By the way, you are quite a librarian-type yourself, Lynd Ward’s Bear book won the Caldecott for the “most distinguished” drawings this year. I still don’t love his work.

But I love your work and you too. HURRY WITH THAT CARBON. HOW COULD YOU HAVE FORGOTTEN A SECOND COPY AFTER ALL THESE YEARS!

Jon and Mac discussed this letter over text.

MAC: Hi Jon.

JON: Hi Mac.

MAC: OK first of all, I just want to say Ursula is a great name. Like, an all-time name. Has any name been done dirtier by a Disney villain?

JON: (Side note: Howard Ashman the Disney lyricist who, it seems, basically wrote The Little Mermaid, has an amazing documentary about him on Disney+, and when he talks about “Poor Unfortunate Souls” in it he is so proud, and he should be.)

MAC: “Ursula” doesn’t even make sense as a name for a sea witch. It means “little bear.”

JON: Yeah. Maybe Le Guin made it “witchy”?

MAC: Oh wow, do you think it is a Le Guin tribute?

JON: I do now.

MAC: That is wild if so. There must have already been a bunch of kids named after Ursula K. Le Guin, because she rules, and then Disney was like, “Oh, this is a good name for our octopus witch,” and ruined everything for most of those Ursulas.

(I say most because a few Ursulas might have been excited to be associated with Disney’s Ursula. Kids — as we maintain around here — not being a monolith and all.)

JON: (Disney’s Ursula post up in drafts, now.)

MAC: (You’re still thinking about “Poor Unfortunate Souls.”)

JON: (I am.)

MAC: Anyway.

This letter is most famous for the phrase “good books for bad children.”

Deservedly.

It’s a great line.

But here is a question:

What do you think “good books for bad children” actually means?

JON: Right.

Like I’d believe she thinks bad children are the best children.

Or at least the more interesting ones.

MAC: For sure.

Nordstrom is pro-bad-child.

JON: And the harder ones to reach. Therefore, when you get them, that’s the true measure of great work.

MAC: I know some people get hung up on Nordstrom calling kids “bad.” It’s a taboo.

JON: It’s so cathartic to do it though.

MAC: There’s a large contingent of people who believe you should never describe a child as bad, regardless of any complex meaning you might be chasing, or your desire for verisimilitude in dialogue, or just your noble literary intentions.

I know this because they leave nasty reviews on my books where I call kids bad.

(My own personal belief is that it’s fine to call a kid bad but you should never call one of my books bad, especially on Goodreads.)

JON: (Dedicated Goodreads post up in drafts, now.)

I think that the people who say that have no understanding of what Ursula means by bad kids.

MAC: Totally agree.

Nordstrom is fond of bad children. She is on their team.

On the opposing team is anyone who wants to use literature as a means to “fix” those bad children.

(And many people who believe you should never use the word “bad” nevertheless want to use books to teach bad kids to be good.)

JON: Yeah. I think she might mean kids that are having an especially hard time accepting what it is they are being shown as The World, and reacting accordingly. She publishes and champions people who feel the same way.

MAC: Yeah, and she wants to publish books that validate their complicated lives and show the messy morality of the world.

But (and here is the other way people get this quote wrong imo): Nordstrom is not being amoral or nihilistic.

JON: No! And also in the same letter she refers, more than once, to adults as “finished” even though I don’t think she believes that they are, or that anyone ever is, it’s just that kids know they’re not and adults often don’t.

But she’s not condemning any kid to their fate.

Or maybe she does think adults are finished? What do you think?

She doesn’t like them, regardless.

MAC: Mmm. My sense is that Nordstrom’s basically sincere when she calls adults finished. At least, she believes the fact that adults think they’re finished, regardless of whether they actually are, makes adults much less interesting readers than kids.

But I might just be projecting.

Because I believe that.

JON: Yeah.

Also I’m 43 and I’m currently the least finished I’ve ever been, feels like.

So I’m with you.

And her, maybe.

MAC: This letter is also famous for Nordstrom describing her job as publishing good books for bad children. But she also describes her job as “praising the Lord . . . in my own modest, harassed, untalented fashion.”

And those definitions are not contradictory.

Meindert DeJong was a religious guy. He went to Calvinist schools and, at the time of this letter, was working at a church.

(Although he is obviously also trying to quit his job at the church.)

But this is a pious man. And it is to him that Nordstrom describes her work as publishing good books for bad children — because she knows he’s a real writer, which is different from a pastor or teacher.

JON: Yeah, he knows how to wade out into it.

MAC: And though Ursula was not to my knowledge particularly religious, she also describes her work as an editor in terms of a sacred vocation — and I think that’s because she recognizes literature’s profound and particular place in a kid’s moral life — because it’s rooted in sympathy for the child and driven by a search for truth. It’s not a tool adults can use to correct or coerce children into good behavior.

JON: Feels like coercion, in any direction, is one of the main things that any “bad kid,” and any adult with the kind of holy anger we’re talking about, is furious at, and actively trying to take down.

MAC: Before we go: I find it moving how exhausted and discouraged Nordstrom is. Librarians are hating her books, Harper titles are being outsold by uninspired competitors, the literary establishment doesn’t think children’s literature is important.

JON: Right. She is in the middle of, indeed leading, one of the Great Periods for this work. And she feels like this.

MAC: I have a tendency to romanticize what it would have been like to make books then. I picture Ursula Nordstrom as all powerful, swirling around, effortlessly making magic stuff happen every few seconds.

But that’s the other Ursula, the sea witch.

JON: Yeah it’s enough to make you wonder if it’s felt the same for a long time, doing this.

Maybe we’re just as good as Ruth Krauss, is all I’m saying.

MAC: Finally, we get to the real point of this post.

But yeah, Ursula Nordstrom had to fight.

And unlike Disney’s Ursula, Ursula Nordstrom won in the end.

Spoiler alert.

(For both Disney’s The Little Mermaid and the history of 20th century children’s literature.)

JON: (Just when you thought maybe Ursula Nordstrom got stabbed in the belly by a ship’s mast.)

MAC: OK, the official Looking at Picture Books Children’s Literature Ursula Power Rankings:

Nordstrom

Le Guin

The sea witch

JON: (Dedicated post on how impossible it is to rank the first two against each other in the drafts, now.)

I think ‘bad children’ is a kindness. It’s as exhausting to be a good child as it is to be a finished adult. Both are invented constructs to make us feel like we can’t feel, like we must be guided by rationality instead of emotions. I think she is saying that she is publishing good books for children with big untethered authentic feelings. Whenever people say ‘is she a good baby?’ What they really mean is does she sleep? (Good) Does she cry? (Bad.) It is a terrible thing to ask a parent. I also think she believes you can be an unfinished adult who still has a living child inside you. It reminds me a lot of C.S. Lewis. “When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”

Speaking of The Little Mermaid movie ruining the name Ursula . . . thank you for not mentioning the name of the Little Mermaid.