Shortcut

Jon and Mac consider: a brush with death, meeting your heroes in a public restroom, letting the kids WHOO vs WHOO-ing yourself, Jon's big smart theory about Trains and the Human Condition

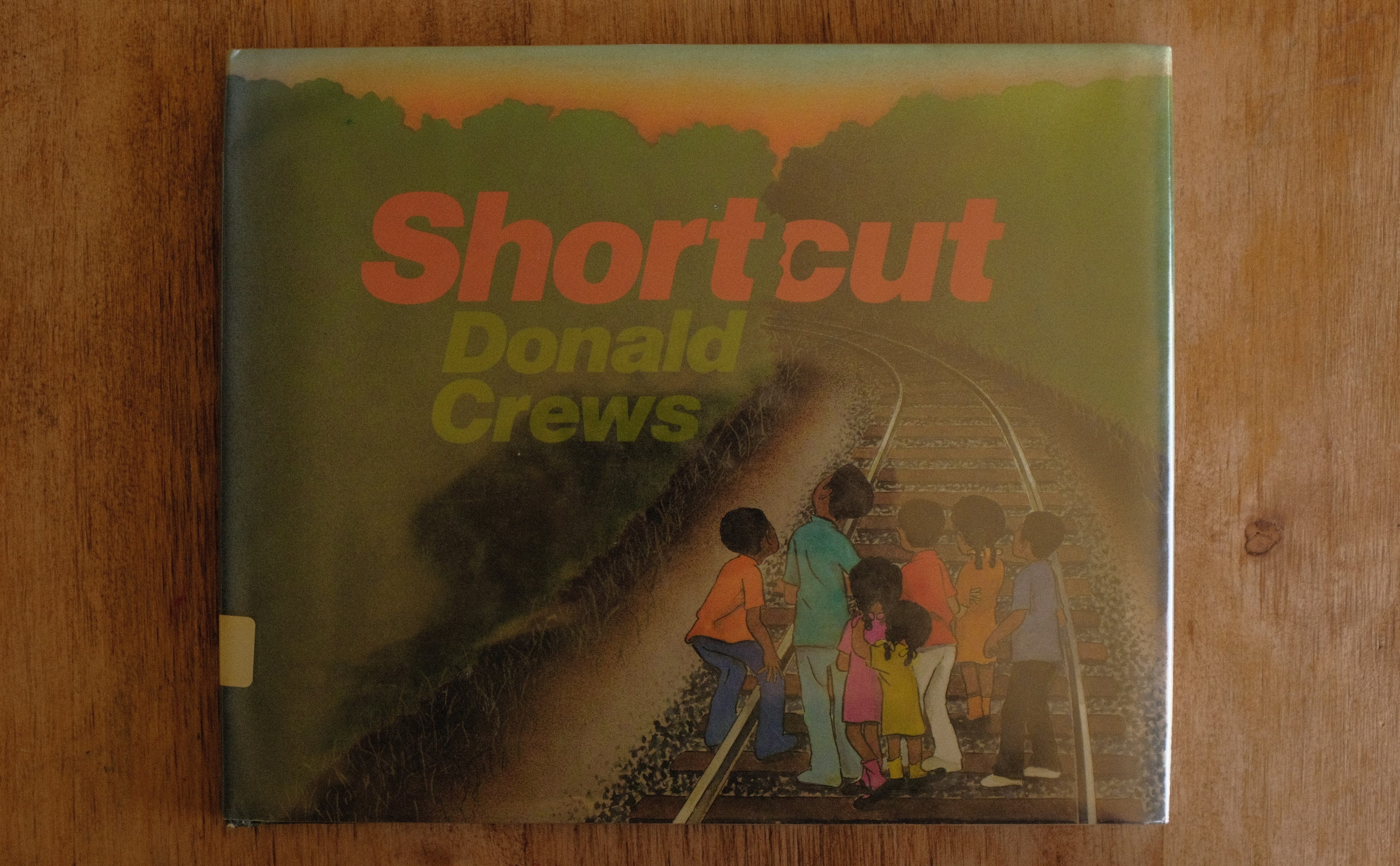

Shortcut, by Donald Crews, is a picture book about seven children who have a near-death experience. Crews is a picture book titan, but Shortcut is an under-acknowledged masterpiece. Crews’s most famous work is probably Freight Train, a concept book that introduces a train’s many cars, then describes the train speeding away. Shortcut is also about a train, but this is a very different book. (Really, Shortcut is unlike any other picture book I’ve read.) The story unfolds in three movements. In the first, a group of children ambles down a railroad track, oblivious to an oncoming train until it is almost too late. The second section is a breathtaking series of spreads that depict a train roaring past. In a brief coda, the children react to their brush with death. Published in 1992, Shortcut still surprises. It’s an innovative and exceedingly well-designed story, a testament to the possibilities of the picture book. It’s also a massively entertaining read-aloud.

Jon and I had the following conversation over text. —Mac

MAC: Hi Jon.

JON: Hi Mac.

MAC: I often tell the story of when I met Donald Crews. We were in a men’s bathroom. I was very excited (I am a big Donald Crews fan), and I walked up to introduce myself while he was washing his hands.

His vibe was polite, but his vibe was also, “Why are you doing this in a men’s bathroom?”

JON: Sure.

MAC: But although I have told this story about embarrassing myself many times, I don’t usually mention that...

Jon, you were also there.

In the men’s bathroom.

JON: Yes.

MAC: And after I said goodbye to Donald Crews — at which point he was visibly relieved to be done talking to me — Jon, you proceeded to introduce yourself to him, in basically the identical manner.

JON: Yes. I think we kind of surrounded him.

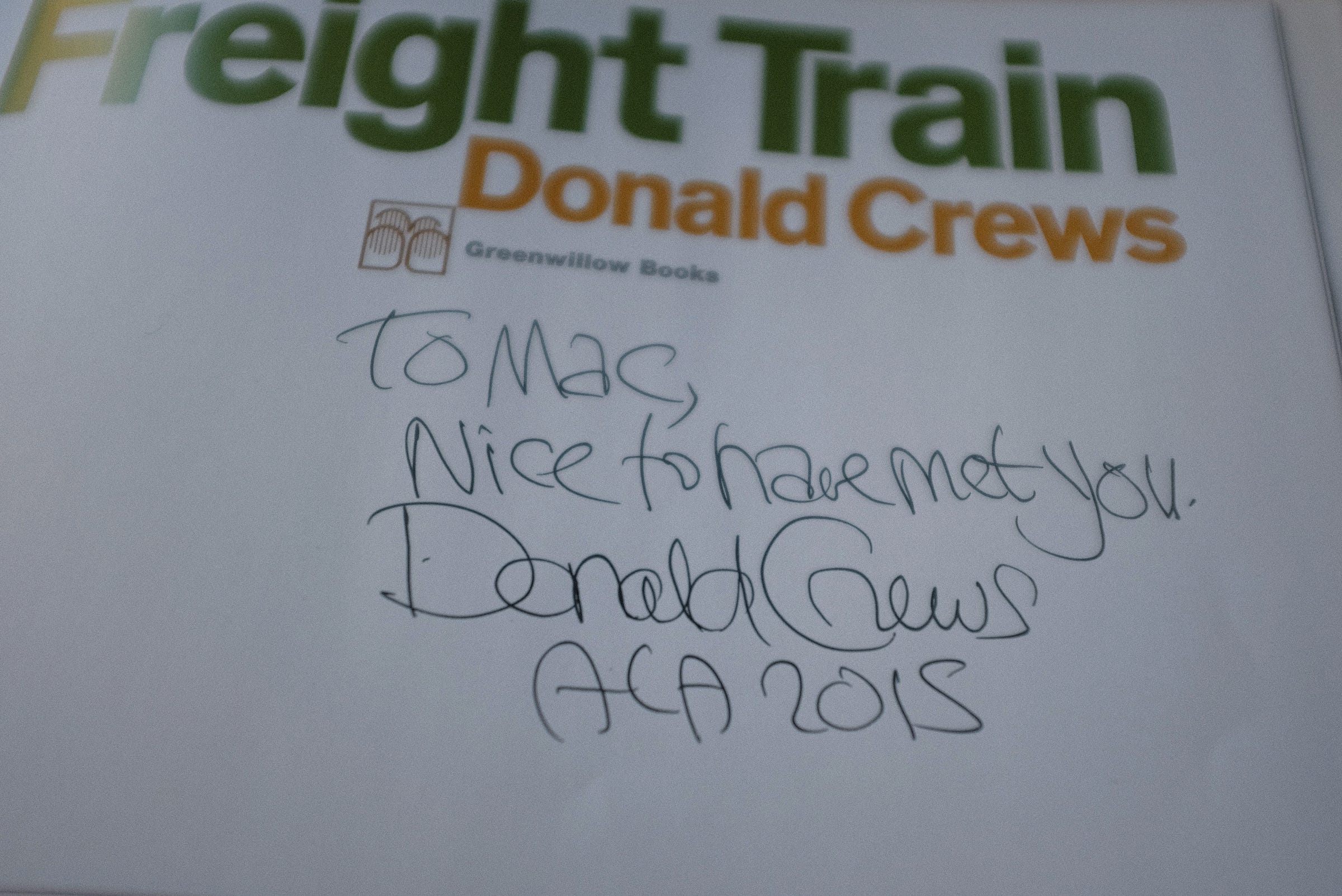

MAC: Donald Crews signed my copy of Freight Train: “Nice to have met you.” It’s clear from the verb tense that Donald Crews was already looking forward to the whole encounter being over.

JON: “Glad to have that over with.” —Donald Crews.

The reason we were all in the men’s room (besides the obvious reason) was that we were at the Caldecott/Newbery/Legacy banquet, and Donald Crews had just won the Children’s Literature Legacy Award. And our book Sam & Dave Dig a Hole had just won a Caldecott Honor.

JON: Right, so it wasn’t SO weird to say hi in the bathroom. We were all back there as AWARD WINNERS.

MAC: I did mention to Donald Crews that we had just won a Caldecott Honor in the men’s room when I perceived that the interaction was going “off the rails.”

(Donald Crews train joke.)

JON: You should’ve said that in the bathroom!

MAC: What, “off the rails”?

JON: Yeah! Would have fixed everything!

MAC: He does love trains. Donald Crews had just given his big speech, and there was this line I still think about.

It started, “Many of my books are taught in school and catalogued as transportation...” And I was bracing myself because I thought he was going to do some version of the famous Sendak line, “I don’t write books for children; I write books, and people tell me they’re for children,” a line (as I’ve said here before) I hate.

So yeah, I thought he was setting up a big “but.” As in,

“Many of my books are taught in school and catalogued as transportation...

…but they’re really about the human condition.”

JON: Some crap like that.

MAC: What Crews actually said was:

“Many of my books are taught in school and catalogued as transportation, and that’s fine with me. I enjoy finding the exciting details of a vehicle’s trip through thirty-two pages.”

His passion for transportation was so evident, and he was so comfortable with himself. He loves transportation so much. So much so that his books about transportation become... well... about the human condition.

JON: This gets into something we talk about sometimes, too, which is that books for kids should be allowed to be about the thing they’re presenting as interesting, and not using that thing as a trojan horse for what you think books ought to be about. If you’re an adult making a book about trains, and you’re a complex, interesting person, trust that you’re going to imbue it somehow with something larger — either on purpose or not. It’s ok, very ok, to just keep your eye on the train part.

That said, we now present a book that is about so much more than trains.

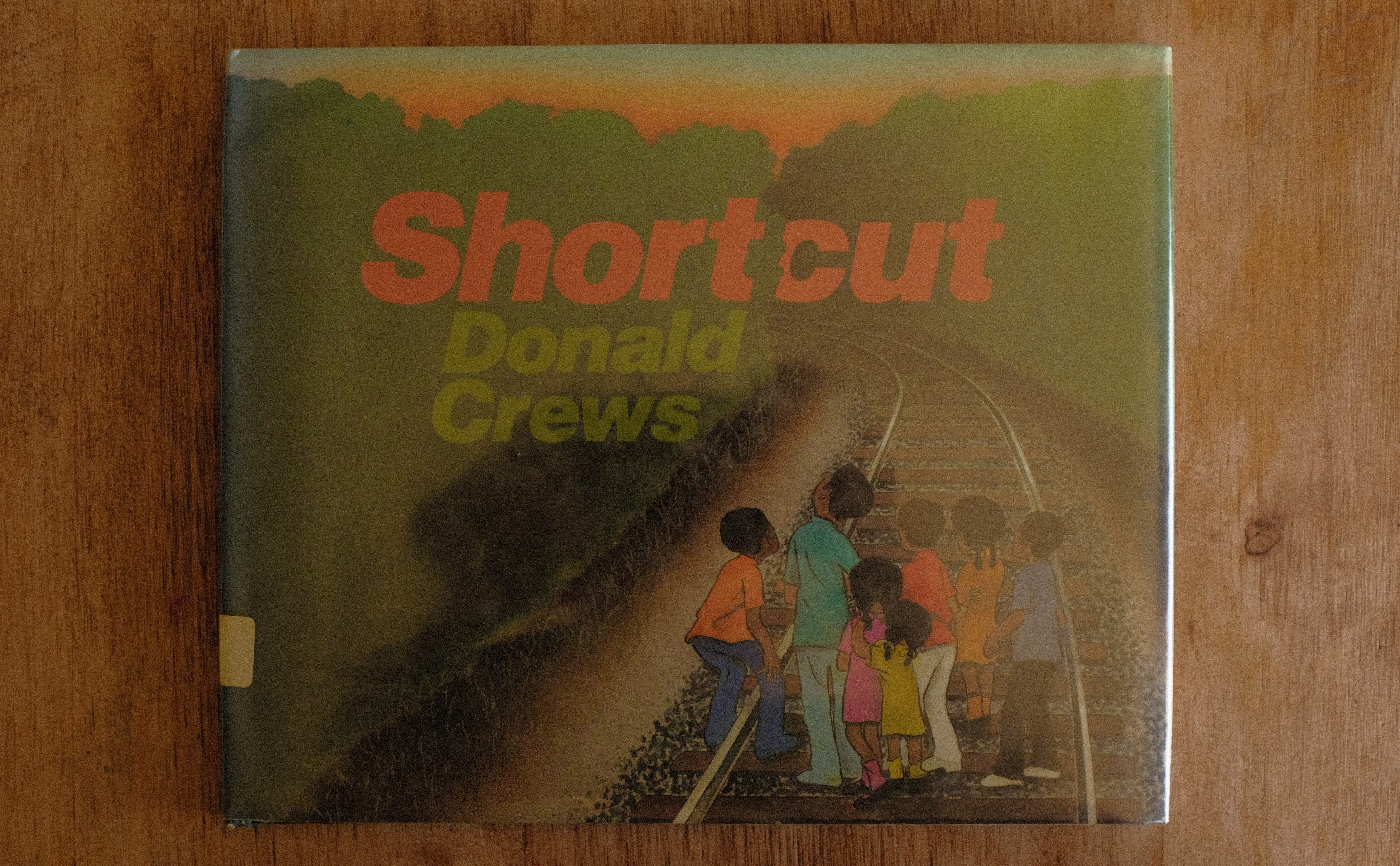

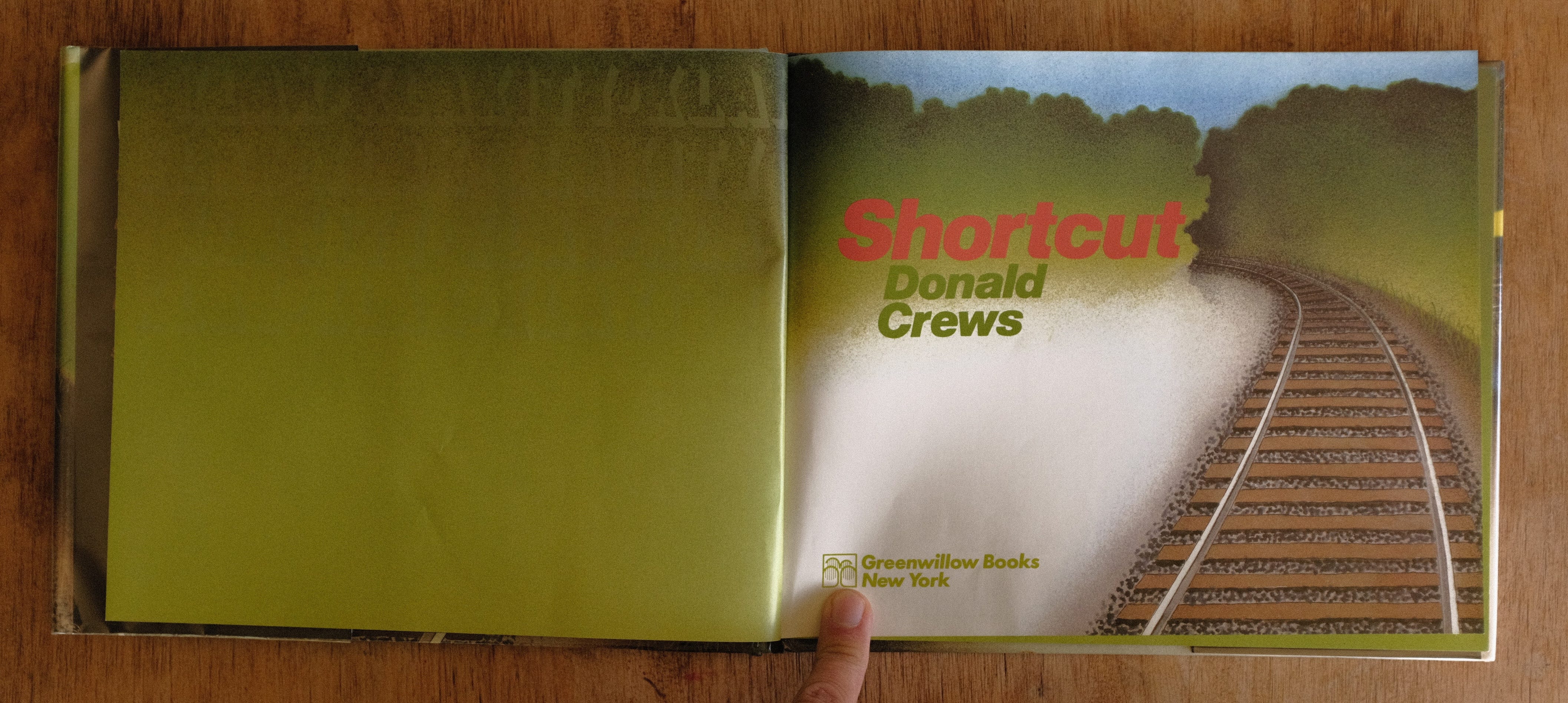

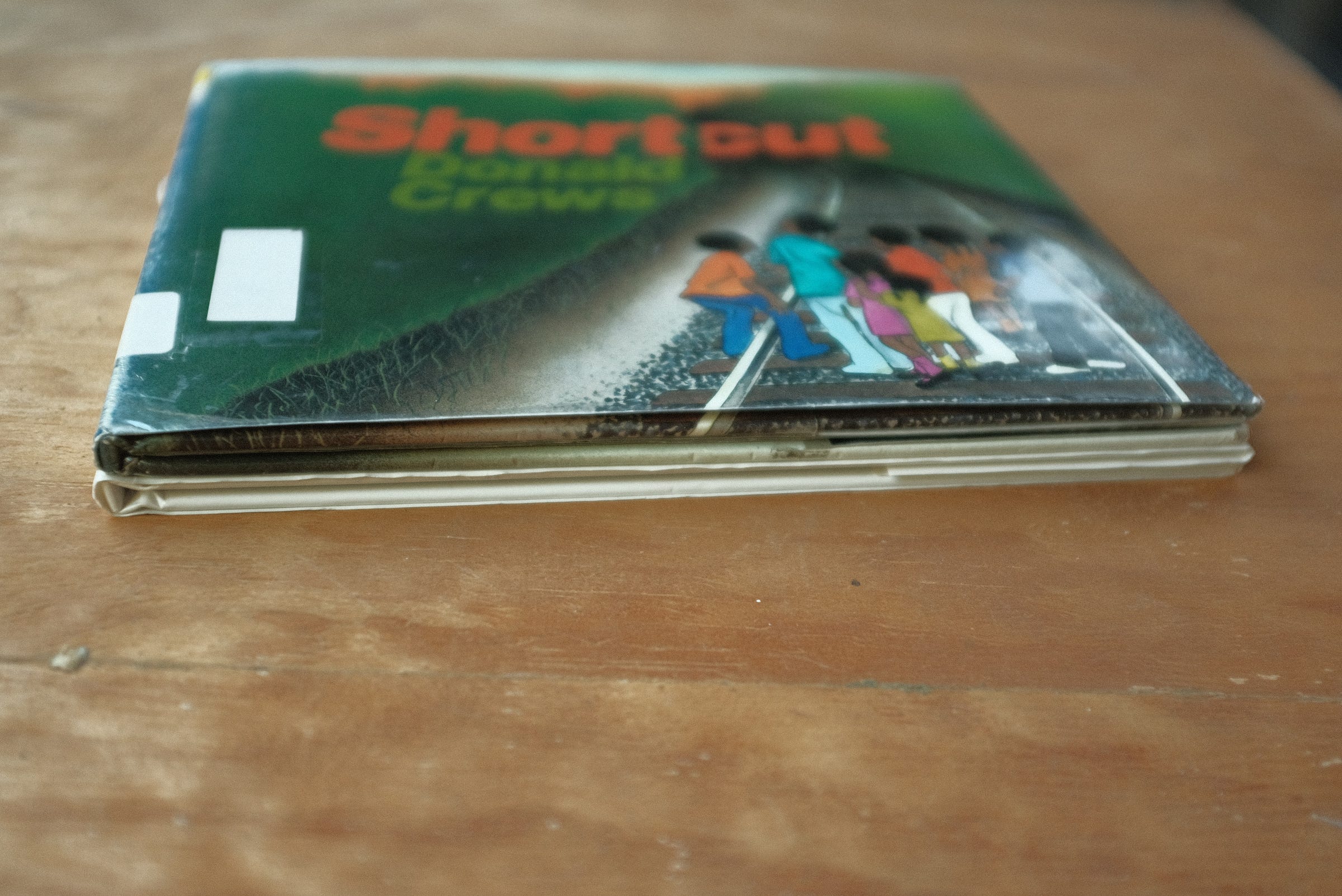

Let’s talk about the cover.

It seems relevant that Donald Crews trained as a graphic designer at Cooper Union in the late fifties. Then, as a soldier stationed in Germany in 1960s, he fell in love with the Swiss Design movement, which emphasizes minimalism and clean typography.

JON: A lot is rightfully made of Eric Carle’s pioneering work with straightforward sans serif Swiss fonts like Helvetica in picture book design. As far as I know, he was one of the first people to use fonts that were mainly meant for, like, pharmaceutical companies, to instead lay out a picture book. But Eric Carle never made one of his titles into a literal train of death coming around a corner.

MAC: Yeah, I was going to say that the title was going to run over the kids, but really, the word “cut” is going to run over the kids, which is even more menacing.

JON: What Crews does here is so interesting. He’s using a very straightforward font, Futura, which is, like Helvetica, very straight and not moody on its own, and with a few choices he makes it really, really ominous. He’s italicized everything — giving it this movement against a languid soft landscape — and he’s used the bulk and clarity of the lettering to chop up that “c” and show it coming around the corner, an idea that would’ve been fussy with a more complex font.

Also, just to really get exciting, he’s sized “Donald” to the exact width of the “h” and the “t” in “Shortcut;” it is just so, so nice.

MAC: And there’s a group of kids frozen in peril, (figuratively) tied to the railroad tracks like a damsel in a silent movie.

JON: By looking at this, you kind of know most of the book already. He tells you everything.

MAC: It’s a really exciting cover, both from a design perspective and from an “I-am-a-child-who-would-like-to-read-about-some-kids-who-might-get-run-over-by-a-train” perspective.

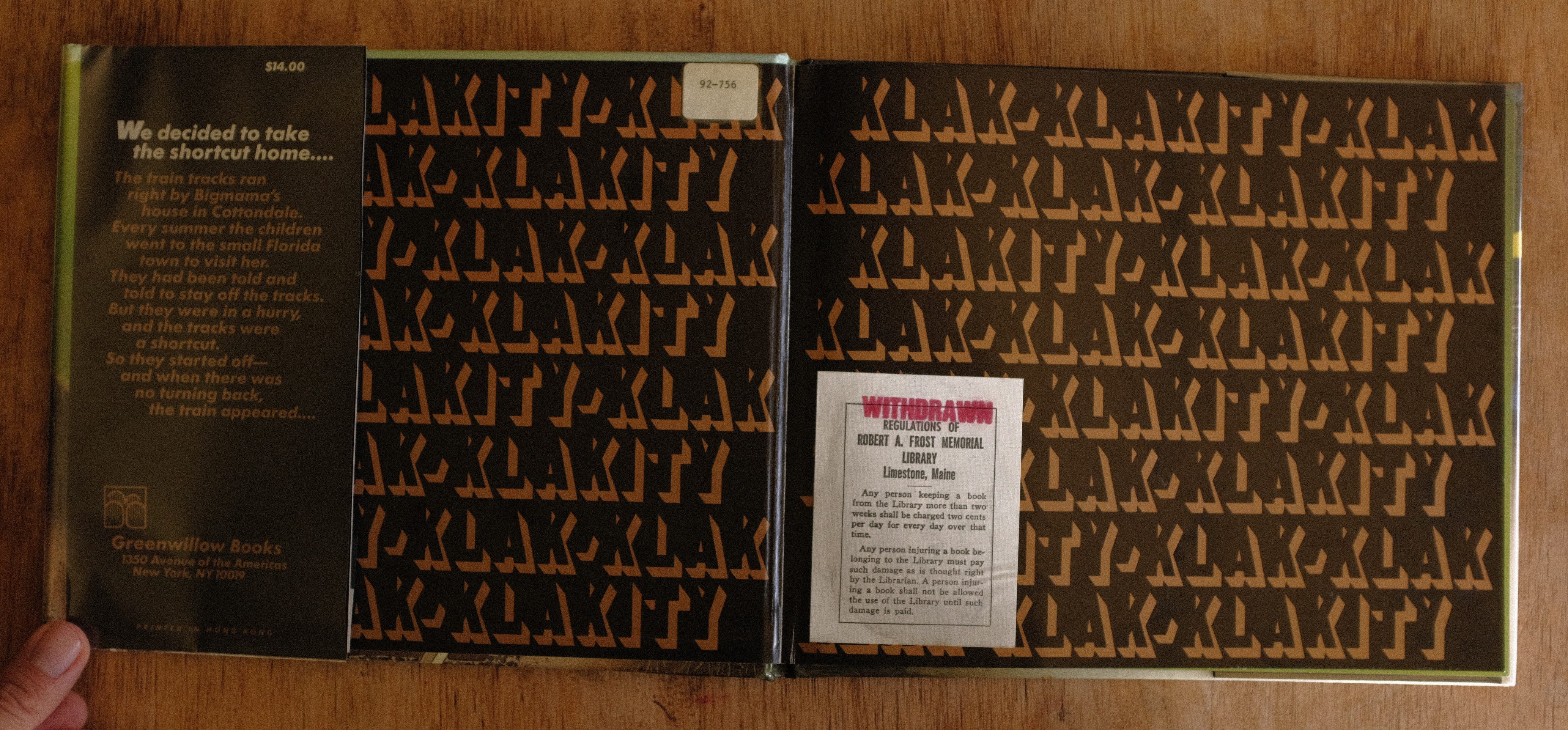

God, and the endpapers are so good and intense too.

JON: SO SCARY.

After that cover?!?! Just KLAKITYKLAKITYKLAKITY in the DARK??

MAC: Jon, you told me you like the title page. Do you want to say anything about the title page?

JON: You could say this about the cover, too, but the visual setup here, of the dense bushes blocking anything on either side, is so great. It will look like this for almost the whole book; you never know where you are, really, how much progress you’ve made in this tunnel of greenery.

But also the cover has a mildly unsettling sunset behind it, whereas here on the title page there is a nice blue sky. It’s earlier in the day. The book will gently run through day into twilight and then into night.

Also... note the very very faint ghost of the endpaper KLAKITYs on the upper left-hand side of the spread.

Scary. As. Hell.

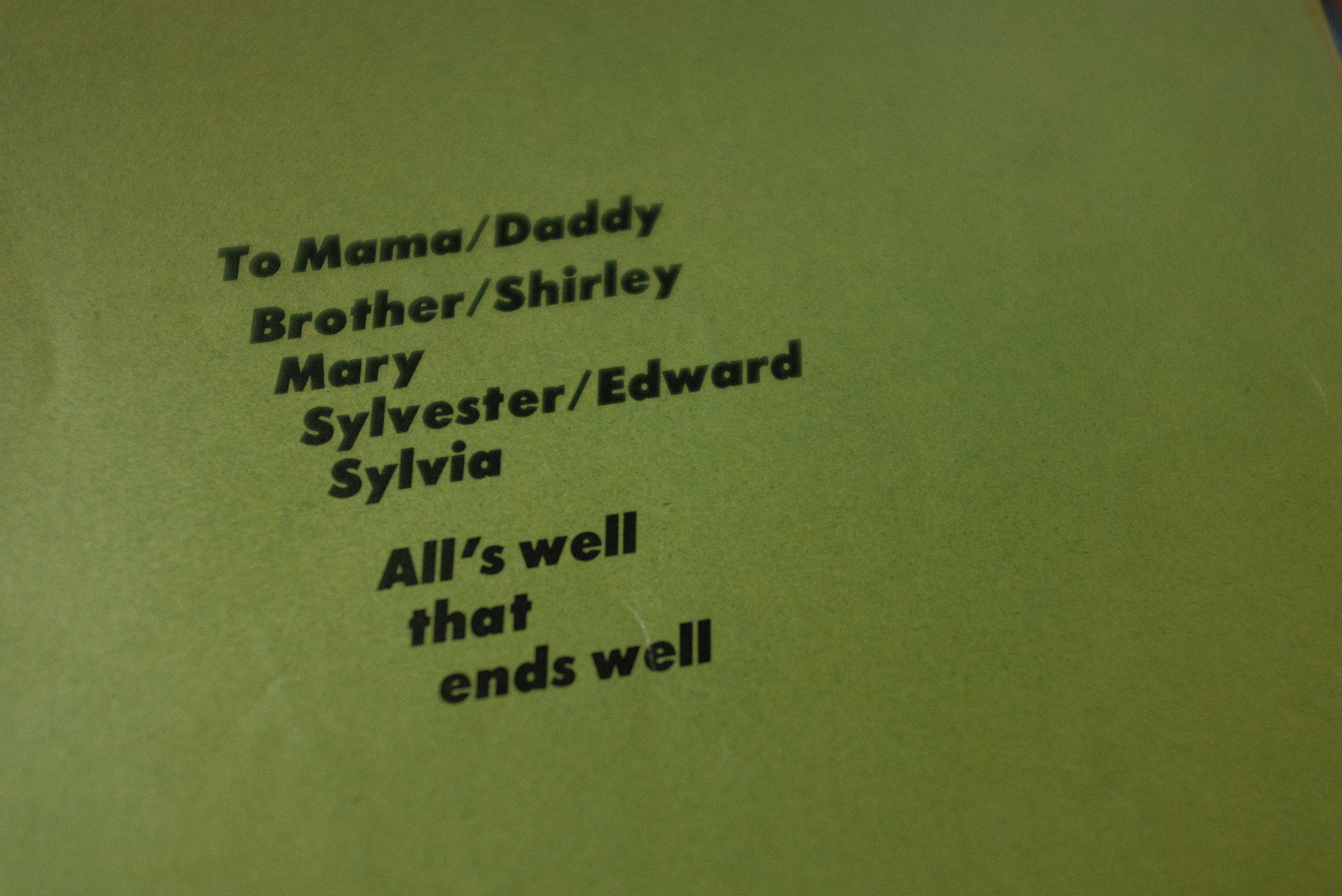

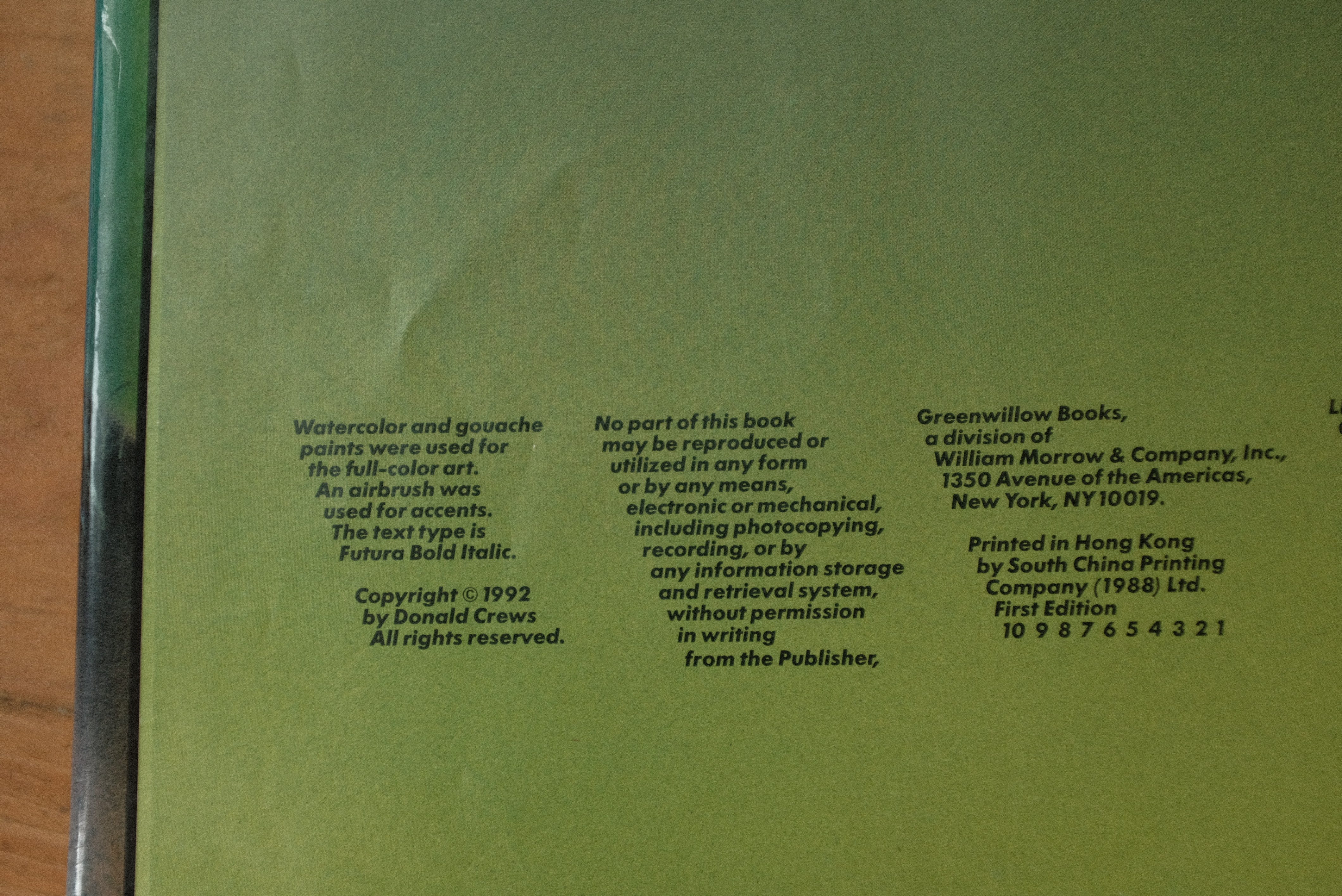

MAC: And then the dedication.

So intense.

By my count, six kids, plus Donald Crews makes seven.

And “All’s well that ends well” — a hint that this actually happened.

Is this the most turbo front matter in picture book history? Most books, in all their pages, do not achieve the levels of suspense Donald Crews has established before page one.

JON: Even just like, “printed in Hong Kong” is exciting here.

MAC: And now, finally we get to the story.

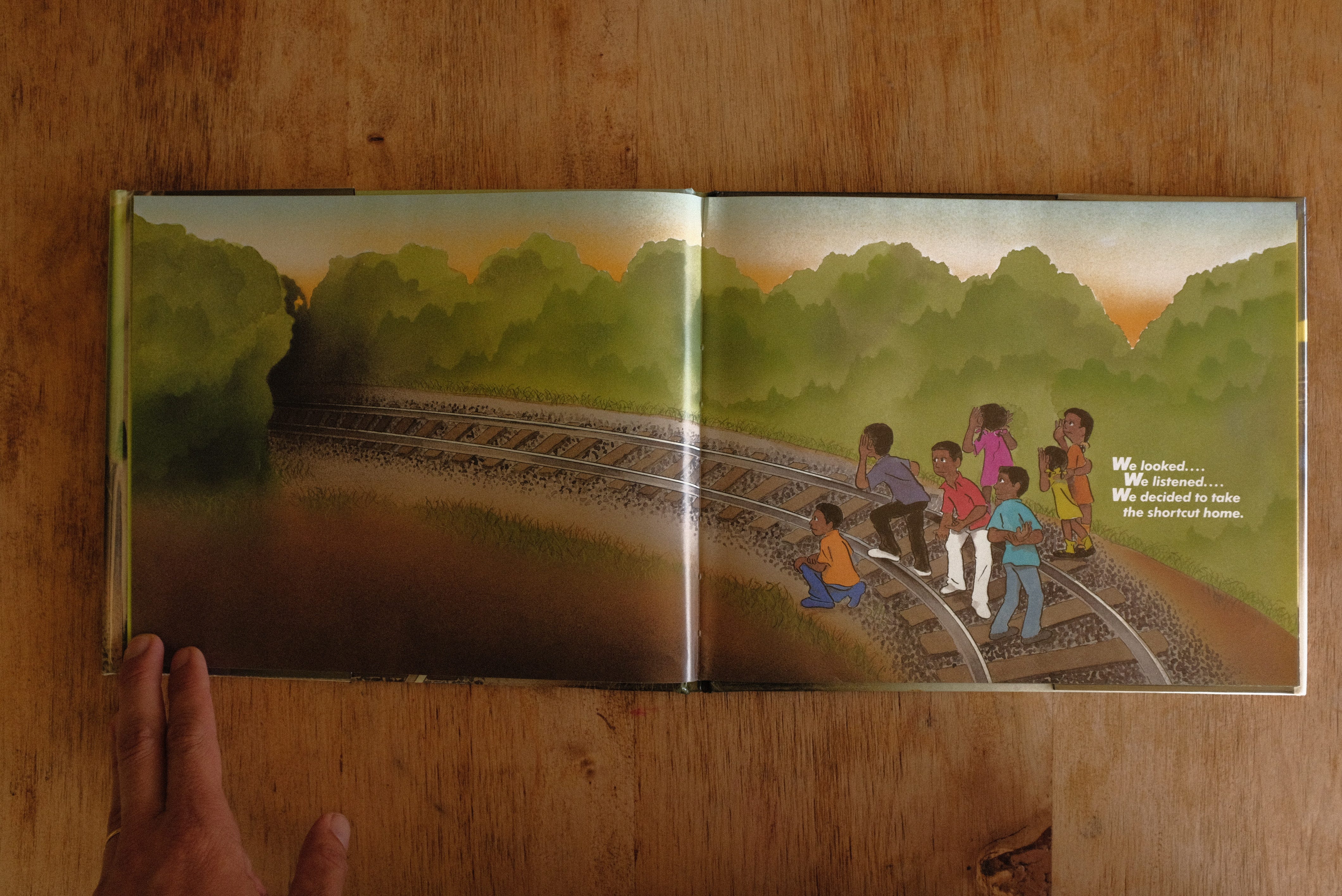

We open with a two-page spread. (The whole book, except for the very last page, is told with two-page spreads.)

JON: I like how the writing here kind of recalls a song they’d teach you about what to do at railroad tracks. We might not know the song specifically, but you can hear the tone. And they’re like, “Okay. So. We DID do that stuff they told us to do.”

MAC: The first-person plural is striking too — all the more so because those heavy W’s emphasize the repeated We. Either our narrator is one of the kids, designated to speak on behalf of the group, or the narrator is sort of a group consciousness.

JON: This actually seems important in another way. There is a bad decision being made here, but it’s being made collectively. If the book had a leader or a main character, you’d maybe shift blame to them and want comeuppance or something, which would complicate everything. But written this way, the reader just kind of lets that rationale go and chalks it up to group momentum.

MAC: Now, a group of kids deciding to take the shortcut home could be the start of a frolicsome adventure story. But Crews makes it clear — in case we have not been paying attention to the heart-pounding copyright page — that this is not a frolicsome story.

Those ellipses tell an adult how to read the story out loud — to lean into the drama. There’s that foreboding gloom coming in from the left-hand side, where the kids are heading. And look at the children’s expressions — very somber.

Their faces change on the next spread though.

Now Crews shows the kids at play. But the words make a hard contrast with this image: “We should have taken the road.”

So even though the kids have relaxed, we have not.

JON: The other thing that changes here is the landscape. There is black on the tips of the greenery now, partly because it’s getting darker out, but the only other time we’ve seen that kind of black used is in the entrance to the shortcut. The gloom is spreading here, like it knows what the narrator knows.

JON: The writing here is so, so great. On the previous page he starts with “We should have taken the road,” and on this page he ends with the same line. Like he forgot he said it already.

MAC: The narrator feels haunted. The whole text is shot through with regret. Which, again, contrasts with the kids here, who are enjoying themselves — singing, carrying sticks, horsing around. A childhood idyll.

The narrator also introduces a big problem: “The freight trains didn’t run on schedule. They might come at any time.”

And indeed, in the upper left corner, there is a word, like a ghost, against the hedge: WHOO.

JON: It’s already coming. Also, it’s already in all caps, like the KLAKITYs. It might be far away, so it’s small, but wherever it is, it’s talking in caps.

MAC: Picture books are well-suited for dramatic irony. You can show things in the pictures that the characters — and the words — aren’t aware of. Rosie’s Walk is a famous example of this. Jon, you and I like to do it.

But this isn’t quite that.

There is another set of words in this book. And really, those words represent a sound. Crews is representing sound on the page.

JON: Yeah, something about the rendering of the sound-words is so effective. It really does look how sound feels. It’s in the air.

This spread looks a lot like the last one. In fact, the next few spreads, even as the problem gets worse and worse, will all look a little like this. We’re in a new place — there’s a ditch with a stream here and there wasn’t before — but Crews isn’t using crazy angles or perspective to ramp up the tension here. He’s very flat, and the kids are flat against it. This serves to enhance the changes he IS choosing to make, namely the time of day and the approaching train.

MAC: The text also describes the ditch: “Its steep slopes were covered with briers. There was water at the bottom, surely full of snakes.” The ditch and its perils are going to be crucial to the story very soon, but Crews leans into the voice here so that its introduction feels natural, not mechanical. “Surely full of snakes” — it’s the way kids invent perils to scare each other (and themselves) when they’re walking around.

JON: The horror of this book is about the steadiness of the oncoming danger on an otherwise slow-moving evening. It’s extra scary somehow for the plainness of it. The train isn’t evil; it’s just a force. Time keeps on going in the sky. Everything is just moving forward, steadily.

MAC: And on each page, the WHOOs get louder, which again, is such a smart and intuitive way to visually represent sound.

When I first started reading this book to my son — who was two-and-a-half —he immediately understood that as those letters got bigger, the WHOOs got louder, and he loved being the train whistle. It’s a great interactive element, a “role” for the child in this very theatrical picture book.

(That is, if you, as an adult, are comfortable delegating some of your storytelling power to children. If you want to maintain total control, you can do the WHOO-ing yourself.)

JON: (And if the child tries their own WHOOs, gently but firmly tell them that you are trying to maintain total control.)

MAC: (“In this house/classroom/dentist’s office, I do the WHOOs.”)

JON: Man, that one WHOO breaking out of the light beam just a little bit. So cool.

MAC: Yeah, he has been so careful to set the WHOOs in the beams. But now that the train is about to run over the kids, the graphic design is getting a lot less Swiss.

JON: The Swiss are only so useful here. You take what you need from the Swiss.

(I’m not even sure Futura IS Swiss.)

MAC: (Shoutout to our Swiss readers, especially those in the paid tier.)

JON: (I looked it up, it’s German.)

MAC: (Shoutout to our German readers, also, especially, those in the paid tier.)

OK, but back to the peril:

We hear again about the briers and snakes. That awful ditch — the terrible pit these kids have imagined — is the only refuge from the threat of this train.

So they jump.

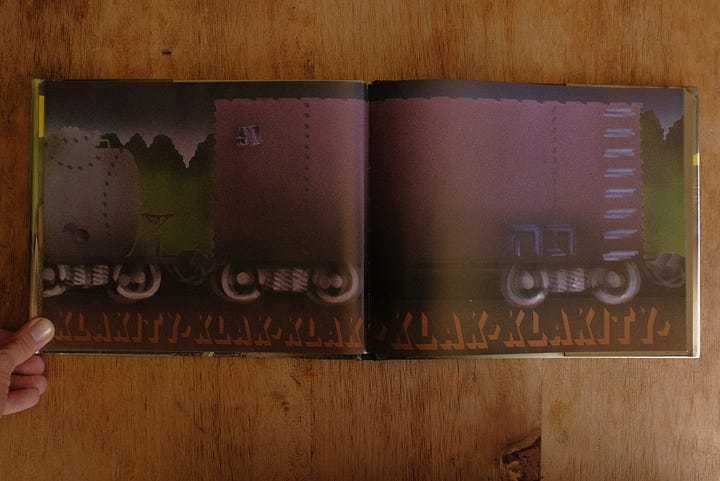

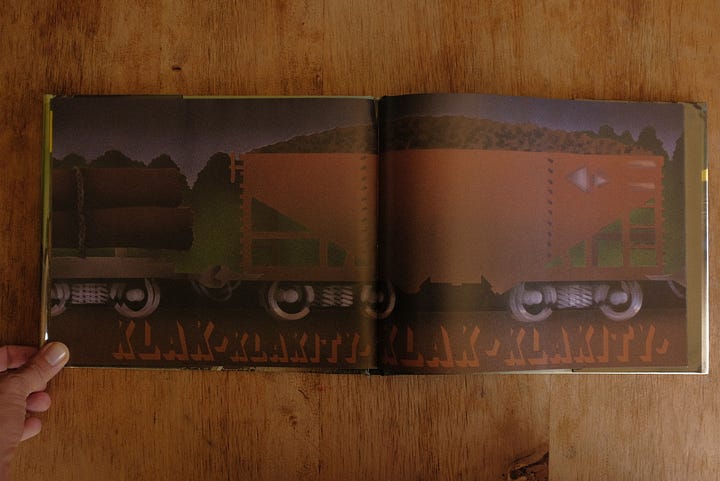

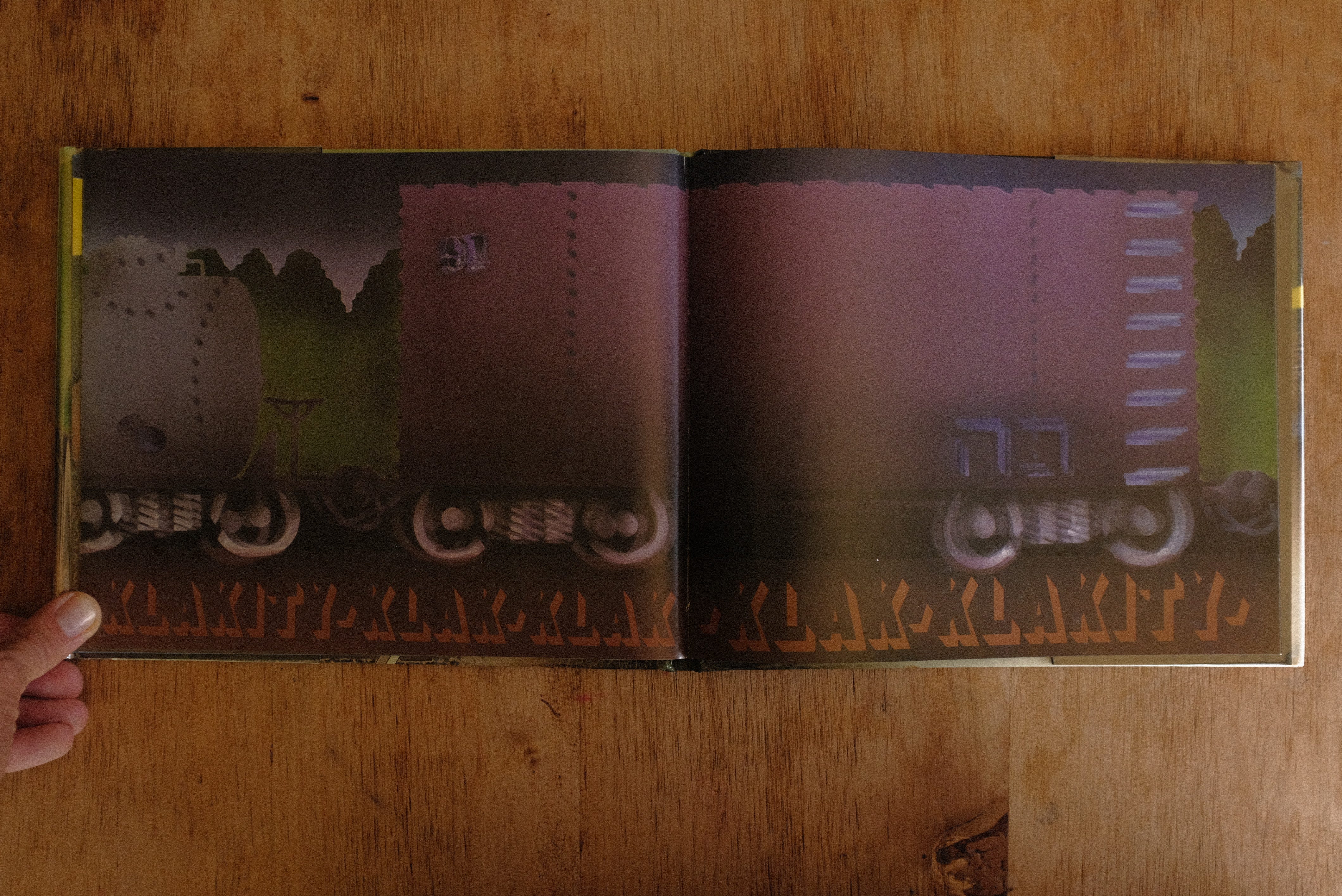

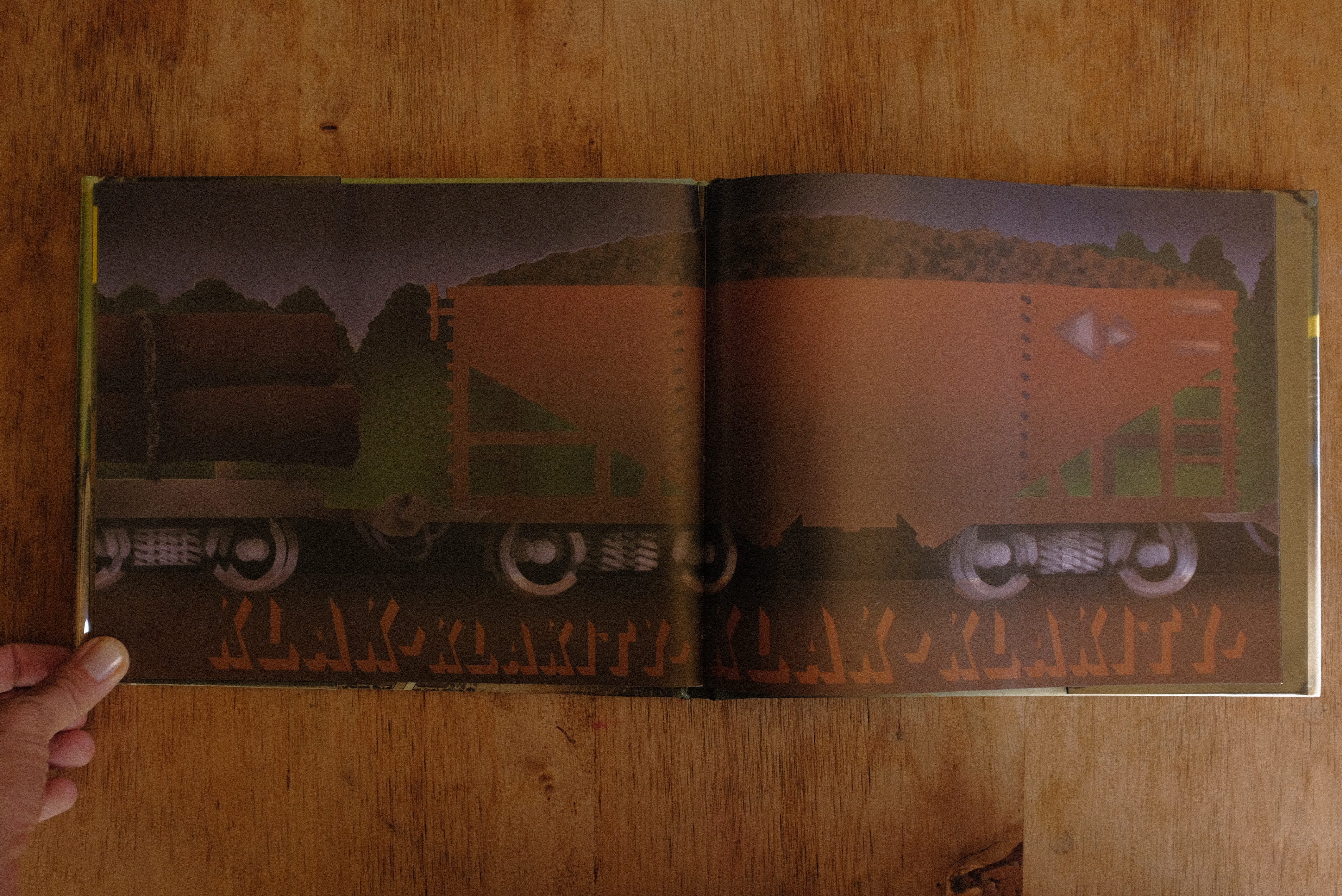

And then, for five spreads, the narrator goes silent.

JON: But the book itself gets very, very loud.

MAC: KLAKITY-KLAK-KLAK-KLAK

MAC: KLAKITY-KLAK-KLAK-KLAK

MAC: This is one of the wildest sequences I’ve ever seen in a picture book.

Ten pages of a train hurtling past — KLAKITY-KLAKITY-KLAKITY-KLAKITY —it’s relentless.

JON: It really, really feels like a whole train.

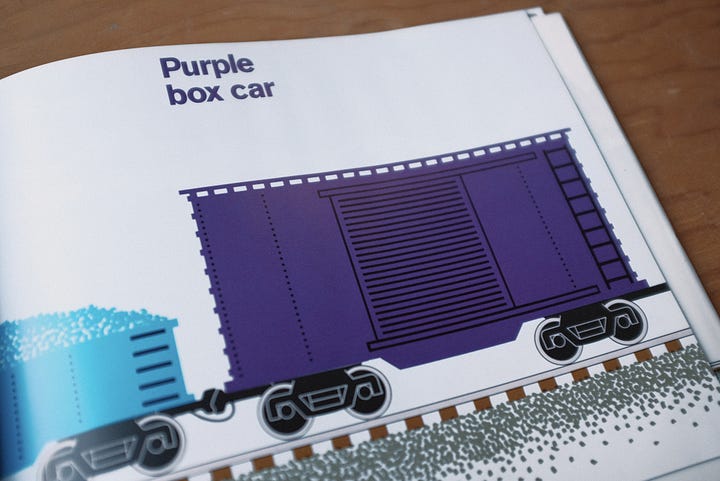

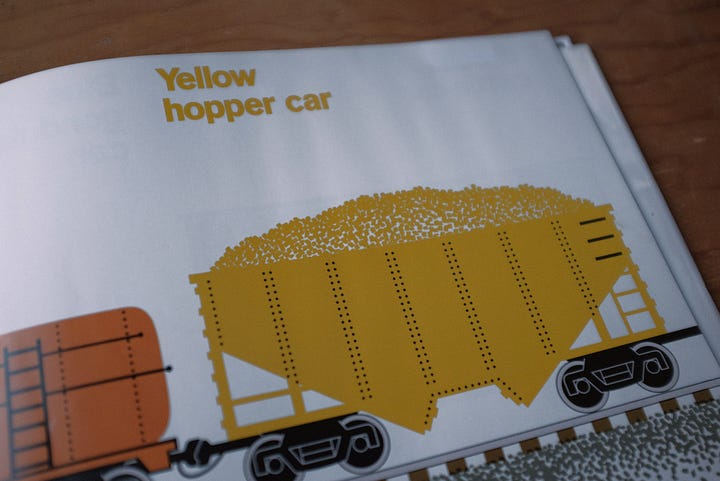

MAC: Can I show you a couple images from Crews’s beloved Freight Train, which was published twelve years earlier, and is a concept book about color and train cars, intended for the youngest readers?

There’s a purple box car and yellow hopper car in both trains.

Want to see something else cool?

JON: I do.

JON: Same trim size.

MAC: Same trim size!

Look, when you find a trim size that works...

I think that’s in the Swiss national anthem.

MAC: There’s some spiritual relationship between these two books.

JON: It ties into the really smart thing I said earlier, I think.

MAC: Which thing was that? Is it the thing about the train as an unfeeling force?

JON: Yeah, the train is just a train. He doesn’t make it more than that, even when it’s racing past in the dark. But it’s the dramatic build, the lighting, the narrator knowing what was about to happen, everything around the train.

MAC: Freight Train is a concept book that packs this unexpected emotional wallop. Crews just describes what a train is and what it does, but the book’ll make you cry. You cathect onto the train.

Now, In Shortcut, the train is just a train, but the human context makes it read as this terrible force.

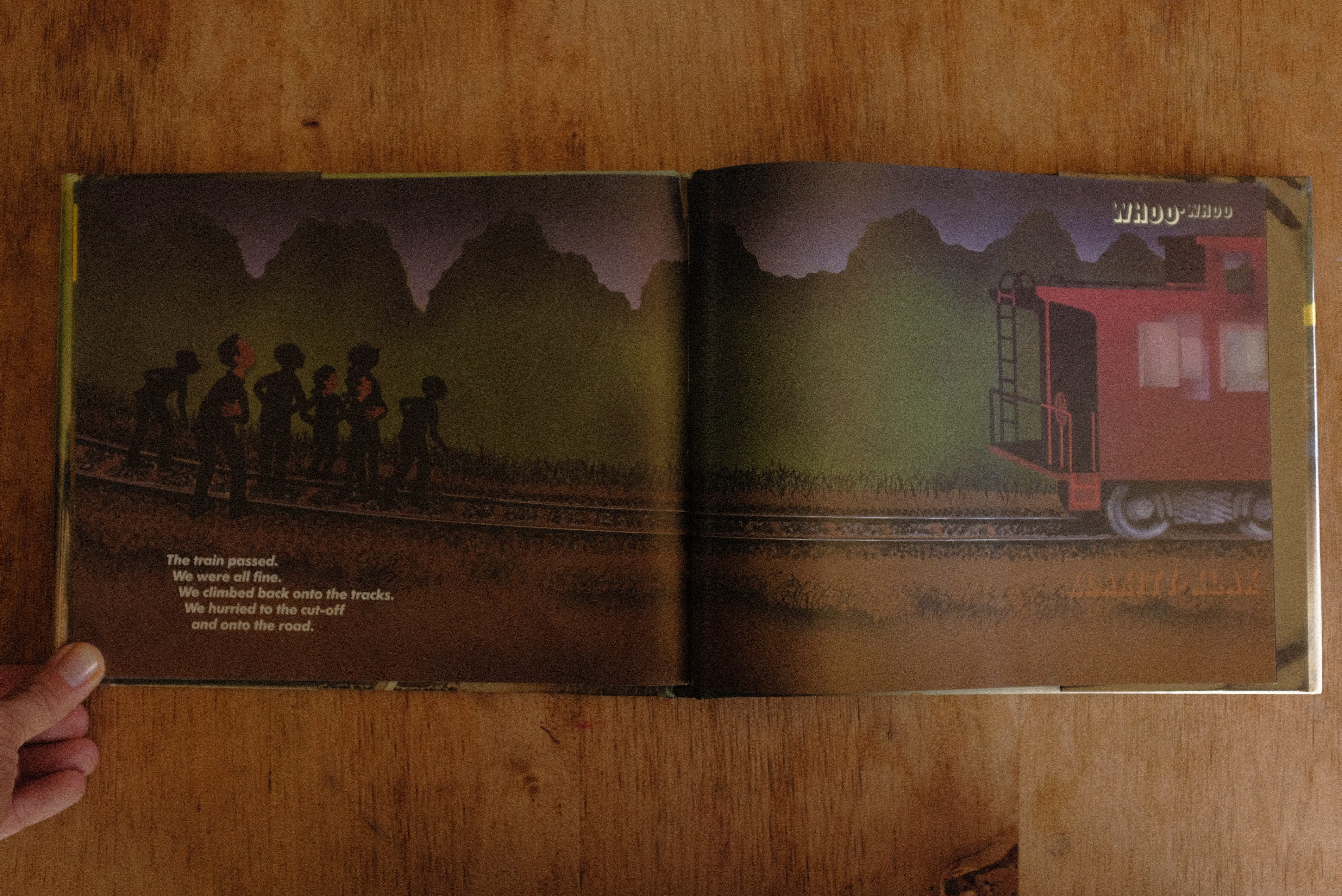

Anyway, red caboose at the back —

MAC: To again return to your really smart point that you made earlier... the train is no longer a monster here. It just feels like a train. And that little WHOO-WHOO — heretofore the harbinger of doom — is now the sound of the train receding.

JON: It’s fun to compare the hurtling train sequence to the wordless rumpus sequence in Where the Wild Things Are. They are handled in very different ways, and time is working differently in both of them — Sendak’s is kind of a montage and this one is almost meant to be in real-time — but both sections have to do with sound, and they both are these crescendos, and then there’s this calm when they’re done and the narrator comes back.

MAC: The narrator does some very important work right away. “The train passed. We were all fine.”

JON: Yeah. Takes care of us right away.

MAC: Right away.

(After five spreads of wondering if the kids died.)

JON: (It would have actually been pretty funny if he said, “We were all going to be fine btw” on the first page of the train going by.)

MAC: Yeah, the “We” is in itself reassuring — the narrator is clearly narrating an event that happened in the fairly distant past, so we know from the start that the “We” of this story are going to be okay.

JON: I want to notice the silhouetted kids on this spread. This is the first time some of them look like that, and the effect IS almost ghostly. I don’t think that’s the literal intention, but it’s so interesting that he did that. Up until now we’ve been shown everybody’s facial expressions, even when they’re scared and yelling.

MAC: Even the three kids who aren’t silhouetted are expressionless.

JON: But what they’re feeling now, it’s not really drawable, or writable. They’re different after this.

MAC: Yeah, Jon, this reminds me of a thing you said on our first book together, Extra Yarn. In that book, the main character, a girl named Annabelle, has something very precious stolen from her. And when you illustrated that scene, the scene where she discovered the theft, you drew a picture of the outside of the house, with a single light on in Annabelle’s room. And you told me that it was such an awful moment for her, and you couldn’t draw it, and in fact you wanted to give her her privacy.

JON: Yeah, you wonder sometimes if you make the choice not to show something because you might have hit the limit of your abilities, but picture books are best when they’re operating at the limits of what words and pictures are capable of describing. Sometimes, neither the text nor the illustrations have to show the thing — instead, the moment or feeling exists in the negative space between the text and pictures. It can be used to describe the indescribable. How does it feel to find out your house got broken into? How does it feel to almost die?

MAC: Right. All the hard work is actually the stuff that leads up to this moment, and if you’ve done your job, you don’t have to draw it, or explain it, and it would be worse if you did.

All right, let’s look at the last page, the only half page in the book. (The recto, the page on the right side of the gutter that separates the spread, is a field of black.)

JON: Gosh, where do you even start with this last page.

MAC: Oh, I was just sitting here thinking that exact same thing.

I saw you were typing, and I was very relieved.

Imagine my face when I saw that that was what you were typing.

You will have to imagine it, because I am silhouetted. It was that bad.

JON: I think this is one of the Great Last Pages.

MAC: I agree.

It feels silly to keep describing various parts of this book with some version of the “best” superlative, but I really do think that this picture book is one of the best ever made, and that its “little-known-gem” stature is not commensurate with its literary achievement.

And a big reason this book is a masterpiece is the way Crews ends it.

OK, so some things that are great about this last page.

First of all, the introduction of adults, here at the end.

This is the first time the narrator has mentioned Bigmama and Mama, and the narrator names them like, “Of course you know who these people are.” It creates this specificity and intimacy here at the end. It’s such a confident piece of writing.

(Bigmama is a character in another Donald Crews book with a lot of the same characters as Shortcut, called Bigmama’s, but this is the first time a lot of this book’s readers will be hearing about these people.)

JON: Yeah, it’s so cool to hear that, and with no other information you’re like, “Dang, yeah, I can understand not telling her, but that’s a big deal for sure.”

MAC: The kids are entering into a conspiracy here — a conspiracy of children— this experience cannot be shared with any adults. It can’t be shared with anyone. They don’t even talk about it with themselves.

JON: The silhouettes are helping with that, too. It’s grouping them into this secret together visually.

MAC: Which makes it even more thrilling that we have just heard about it.

JON: I have a thought on this. It might be the wrong read, but we can’t be afraid of a few of those here on Looking at Picture Books.

MAC: OK.

JON: The secret they’ve got — part of it is for sure just simply, “We almost died; that was pretty dumb,” but there’s something bigger, maybe. I feel like, with the treatment of the train, and the landscape, and the even-ness of everything, it feels like they saw the indifference of the world, like they learned about it in a new way, together. Like, you know intellectually that trains and the big movements of the world don’t know or care about you, but it’s not often you get such a close-up view of it. It’s a dark thing to be shown.

MAC: Oh, so really this is just back to your big smart point from earlier again, huh? The unfeeling train.

Surprise.

JON: Look, I’m just saying, I’m pretty smart.

MAC: Well, I think that’s a great read. Certainly, the kids have changed — in some unseeable and indescribable way that we have to make sense of. Which is something I love about that last sentence.

“We never took the short-cut again.” It reads like a moral, and “not taking shortcuts” has a double-meaning that could easily generalize out into a life lesson. But these kids weren’t shirkers. This isn’t Pinocchio. They took the shortcut because, “It was late, and it was getting dark.”

They didn’t take that shortcut again is just matter-of-fact. They literally didn’t take that shortcut again, because something really scary happened.

Wanna know something weird that I just noticed?

Crews spells it “short-cut” in the last sentence and doesn’t do that anywhere else.

JON: Oh, weird.

MAC: Don’t know what to make of that, honestly.

Does your unfeeling train theory explain it?

JON: Probably it does. It explains lots of stuff. It’s really smart.

MAC: This last image is simultaneously comforting and unsettling — the house is warm and bright and comforting, and it’s a relief to be welcomed back into the world of loving adults. But we also know that these kids won’t be fully themselves when they get in the house.

It’s not a coming-of-age story. They haven’t grown up. In fact they are more estranged than ever from the world of adults. But these kids have changed, and they have a secret. A shared experience that belongs only to them.

Part of the reason they can’t tell Mama and Bigmama, I think, is that Mama and Bigmama wouldn’t get it. And that’s true for a lot of adults. This book might be too scary for many grown-ups, but it’s perfectly exciting to most kids. It’s worth saying that Shortcut is a fun book. It’s a thriller — a perfectly constructed entertainment that leads to this profound last moment.

But I guess it brings up the question: Jon, this story, about seven kids, some of them very young, who do something reckless, and almost die, and whose fate is unknown to us for many pages in the middle of the story — is it appropriate for a picture book?

JON: I think the question, usually, is not about appropriateness, but rather, are you good enough to pull it off.

Please keep doing these forever

Hy guys!

do you know that the FUTURA font (which is German) is the one used by many railway companies for their signs and communication? I think Donald knew...